Gene Andrew Jarrett ’97 Details the Life of Poet and Writer Paul Laurence Dunbar

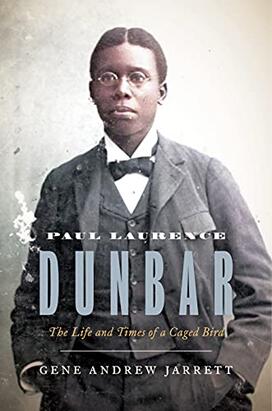

The book: Paul Laurence Dunbar: The Life and Times of a Caged Bird (Princeton University Press), by Dean of the Faculty and professor of English Gene Andrew Jarrett ’97 was published this month to honor the 150th birthday of this Black poet, a pivotal figure in American literature. Jarrett offers the first full-scale biography of Dunbar, who was born during Reconstruction to formerly enslaved parents. This detailed account celebrates Dunbar and his impact on poetry and American literary history.

The author: Gene Andrew Jarrett ’97 is dean of the faculty and William S. Tod Professor of English at Princeton. A specialist in African American literary history, Jarrett earned his master’s degree and Ph.D. from Brown University. He was the first person appointed as dean of the faculty who was not already a Princeton faculty member at the time. Jarrett’s other books include Representing the Race and Deans and Truants.

Excerpt:

CHAPTER 4

The Tattler

Paul and Orville’s bond may have been preordained. Orville’s father, a United Brethren Church clergyman, had married Paul’s parents, two former Kentucky slaves, on Christmas Eve, 1871. Nearly two decades later, both Paul and Orville enrolled in Dayton’s Central High School. Initially in the class of 1890, they became entrepreneurial partners in a short-lived newspaper called the Dayton Tattler. They genuinely respected each other. In the back room of the Wright & Wright print shop—co-run by Orville and his brother Wilbur, and located on the second floor of a building on the corner of West Third and Williams Streets in West Dayton—Paul reportedly scrawled on a wall:

Orville Wright is out of sight In the printing business. No other mind is half as bright As his’n is.

During Paul’s years before the Tattler, he was refining his reading and writing of poems with the help of committed teachers in intermediate school and the guidance of classical curricula in high school, although he needed several years to mature into an excellent student in the classroom. These years comprised a period of personal struggle and self-inquiry; he grappled with his father’s troubled legacy for him and the rest of his family, and he sought to articulate his memories and imaginings in his early fiction, poetry, and drama. Jim Crow racial segregation was not yet officially dismantled right after Paul graduated from district school; it normally kept students, black and white, like him and Orville apart.

Yet they were “close friends,” Orville himself later reflected. “Paul Lawrence [sic] Dunbar, the negro poet, and I were close friends in our school days and in the years immediately following… When he was eighteen and I nineteen, we published a five-column weekly paper for people of his race.” The improbable publication by two young men, one black, the other white, of a periodical for the African American readers of Dayton was the remarkable backdrop to Paul’s transformation into a professional writer—from being the early performer of literature on Easter Sunday in 1884 to an experienced writer and editor by 1891.

Paul’s high school years encompassed the story of how two young men discovered common ground across the so-called color line: not merely within high school classrooms, where curricula forced them to learn the same lessons, but outside them, where newspapers instilled a shared sense of fascination. For Paul, the allure was literary. He was drawn to honing further his exceptional skills of editing and creative writing—the ones that in a few years would elevate his poetry to international prominence. For Orville, the attraction was managerial. As much as he wished to help advance the mission of the Dayton Tattler to provide “all the news among the colored people,” in the words of one motto, he also wanted more business for the fledgling printing press that he and his brother Wilbur co-founded and that helped sharpen the organizational acumen they would bring to aviation in the new century.

Paul’s union with Orville closed a chapter of his life as grand for its achievement as for its gateway toward literary self-expression. By the time he graduated from Central High School, Paul was poised to learn from these experiences and experiments, and to make a crucial pivot. “Prepared to cast our moorings free,” he wrote, as appointed class poet, in his “farewell song” to his high school commencement audience, “[a]nd breast the waves of future’s sea.”

When Paul first began the ninth grade in high school in fall 1886, he was scheduled to graduate four years later, by spring 1890. But he delayed his graduation by a year to pursue an extracurricular interest: newspapers.

Paul was not alone in viewing Ohio as an especially fertile state for newspaper publication. In 1888 a writer in the renowned Scribner magazine called the Midwest “the Centre of the Republic,” a hub of newspaper commerce that served the economic wealth and political influence rising in the “old Northwest Territory” between the Ohio River and the Rocky Mountains. The commercial epicenters of Ohio were Cincinnati and Cleveland. Although paling in comparison to these cities, Dayton joined them in being a node of religious publishing and promising to cultivate its own market of newspapers. Journalism in Dayton began as early as 1808 with competing Republican and Democratic periodicals. By 1890 the market saw the consolidation of Dayton journalism with papers like the Journal, Herald, Morning Times, and Evening News, which all inherited and modified preexisting local papers.

Still, the newspaper was in vogue. The last decade of the nineteenth century belonged to the era known as “more of everything.” Readers craved information, whether education or entertainment. Periodicals ranging from newspapers to magazines, from monthlies to weeklies to dailies, captured an “interest,” according to historian Frank Luther Mott. “And every interest had its own journal or journals—all the ideologies and movements, all the arts, all the schools of philosophy and education, all the sciences, all the trades and industries, all the professions and callings, all organizations of importance, all hobbies and recreations.”

As long-standing Dayton newspapers underwent mergers, rebranding, and political realignments during the nineteenth century, their African American readership remained small in number and fragile as a literate community. Paul continued to write poems but, mindful of these circumstances, anticipated the need to find places to publish them. The growth of periodicals throughout the country intrigued him.

The burgeoning opportunities periodicals offered editors and writers appealed to one Mr. Faber, a Dayton resident and publisher of a newspaper he founded in 1890 called the Democratic. Paul had learned through other local papers of Faber’s interest in boosting its circulation, especially among African American readers. Eventually the two connected, and Paul agreed to help Faber out.

By early June 1890, Paul wrote to Faber that he had “worked the circulation” of the Democratic up to sixty subscribers, “fifty having been agreed upon and having placed the paper in a position to increase steadily its circulation.” Paul swore he “worked hard” for his “promised wages.” So successful was Paul that he boasted: the “little Democratic sheet was becoming popular.” A bitter sense of betrayal tainted Paul’s joy in working for Faber. “I find that you willfully and persistently fail to keep your part of the agreement,” Paul complained, “whether your action is either honest or gentlemanly it is not for one to say.” He felt taken advantage of, “to use a very polite word, induced,” presumably by Faber’s failure to compensate him for the work done. For two reasons Paul bemoaned this problem. The first was personal. He had to wait six weeks for pay, but that was too long; in his words, “I couldn’t afford to walk and wear out my shoes getting news for nothing.” The second reason indicted Faber’s hypocrisy. “I knew your mother and the Faber family when you were exceedingly, yes even distressingly poor,” Paul reminded him, “and I judge that it is no more than right that you after having struggled up through adversities to a tolerably fair place in the world should try to crush and deceive people, who can ill afford to lose, though not quite so poverty stricken as you were when I knew you in past years.” Paul had to quit. The time forced him to consider another opportunity. “Suffice it to say that your actions added to the fact that I have accepted the editor-in-chiefship of the High School Times,” the organ of the Philomathean Society of Central High School, a debate club. Eventually, he became the club’s president.

Fatefully, Paul’s turn toward the High School Times—and, separately, Tomfoolery, a hand-illustrated periodical where he could publish his work, too— allowed him to affiliate with a more homegrown and predictable paper that offered him not money but experience and positions of leadership, the kind of opportunities that his job as a subscription runner did not provide. He also realized that if he were going to be involved in a newspaper for African American readers, he might as well publish or edit one himself. But he needed help.

Paul’s high school classmate came to the rescue. He discovered in Orville an ideal companion in print culture—that is, in the writing and editing of pieces for newspapers, in the enterprise of printing and circulating them, and in the use of them as a vehicle for amplifying an original voice for the good of local readers. Orville had been ensconced in the world of newspapers while growing up. His father, Milton, was editor of the Religious Telescope, a periodical of the United Brethren Printing Establishment, from 1871 (the year Orville was born) to 1875. One Wright biographer notes that the enterprise, “based in Dayton, Ohio, was one of the best-equipped religious printing houses in the nation.” The Wright family was at the epicenter of the religious printing press, enhanced by Milton’s ascension to United Brethren Church spokesman as a result of his editorship.

Even at an early age, Orville developed a profound attraction to newspapers. In 1881 Milton Wright had become an editorial activist of sorts, publishing Reform Leaflets and founding the Richmond Star to promote his opposition to secret societies and to the liberalization of the United Brethren Church. Orville’s older brother, Wilbur, built a contraption for folding the pages of the Star for mailing, as well as a six-foot, treadle-powered lathe made out of wood. When the Wrights returned to Dayton permanently, newspapers—or, more precisely, the technology of printing—held an allure for the two brothers.

Printing so captivated Orville that by the time he entered the ninth grade at Central High School in 1887, classroom education was secondary in his grand scheme of life. Aside from his reputation as a mischievous boy needing a punitive seat in the front of his intermediate school classes, Orville was neither “outstanding” nor “memorable” as a student, but he was a close reader of the extensive library that his scholarly parents compiled at home. Along with copies of the Religious Telescope, Reform Leaflets, and the Richmond Star, Milton stacked the shelves with books by the Greek philosopher Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, English historians Edward Gibbon and John Richard Green, French historian François Pierre Guillaume Guizot, Scottish biographer James Boswell, Scottish novelist Sir Walter Scott, and American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne. The library also included theological, scientific, and encyclopedic texts. If Orville’s knowledge of printing was born during his handling of United Brethren Church leaflets and periodicals, it matured with his combing through one particular book: Cyclopædia: or, an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences.

Published in two volumes in 1728 by Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopædia was a massive book, which Orville plumbed to figure out printing. In the second volume he learned about the “Art of taking Impressions with Ink, from Characters and Figures moveable, or immoveable, upon Paper, Velom, or the like Matter.” This section of Cyclopædia contained a history of printing, including the distinction between “Common-Press Printing” (for books) and “RollingPress Printing” (copper plates for pictures), the origin and invention of printing in the West, and the modern progress of this industry. Orville learned the role of a compositor, the method of printing and making ink, and the components of the printing press. Though the reference work was compiled more than a century and a half before he thumbed its pages as a teenager, Orville, along with Wilbur, discovered in it a theoretical blueprint for them to establish their own printing office.

Over time the Wright brothers came to master the rudiments of the printing business. They learned to divide the business into the three areas of composing, pressroom, and warehouse; to enlist the proper personnel and apprenticeship for the jobs; to allocate workload and hours; and to manage the printing process itself, such as typesetting, composition, correcting in metal type, purchasing and preparing paper and ink, and identifying a warehouse to store the newspapers and ready them for delivery. Over time they would learn the economic risks of printing, such as the engagement of customers, the price of resources and technology, and the scaling of newspaper prices according to supply and demand. Out of the experience of printing short-lived periodicals like The Midget and The Conservator, or publishing church pamphlets like Scenes in the Church Commission, they launched the Dayton imprint “Wright Bros.: Job Printers” out of their home on 7 Hawthorn Street.

By 1889, Orville decided that, more than school, he wanted to be in the printing business. On March 1, 1889, he began publishing the West Side News, one year after he had constructed a large press to handle complex or demanding newspaper jobs. Geared for the West Dayton community, the weekly paper ran for a mere thirteen months, but Orville remained committed to newspaper publishing. The paper “was intended to function as the keystone of his small printing enterprise,” notes biographer Tom Crouch, “producing enough income to justify his decision to quit school, forego college, and devote all his time to publishing.” To Orville, classroom education was a distraction. The motto of his new paper, the Evening Item, which appeared less than a month after its predecessor the West Side News, was that it would print “all the news of the world that most people care to read, and in such shape that people will have time to read it.” It would also cultivate “the clearest and most accurate possible understanding of what is happening in the world from day-to-day.” Despite its admirable mission, the Evening Item died even faster than the West Side News. Lasting only four months, the Evening Item closed down in August 1890, unable to hold its own among the Dayton competition, which included more than ten papers. But with the rebirth of the family printing business as “Wright & Wright,” Orville’s new operation could serve Dayton businesses seeking to publish directories, reports, programs, posters, advertising cards, and letterhead. The printing office moved a little more than a block away, from Hawthorn Street to the corner of Third and Williams Streets.

Within the crucible of the publishing world, Orville and Paul linked up at the outset of academic year 1890–1891. Paul was now a member of the class of 1891, given that he was considerably ill during large swaths of calendar year 1889, likely forcing him to take an academic leave of absence overlapping his original third and fourth years of high school. (Indeed, he started the ninth grade in academic year 1886–1887, so now he would need five years, not four, to graduate.) As they approached the Christmas season of 1890, the white printer and the black editor looked forward to publishing a newspaper for local African American readers.

Excerpted from Paul Laurence Dunbar: The Life and Times of a Caged Bird by Gene Andrew Jarrett. Copyright © 2022 by Gene Andrew Jarrett. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

Reviews:

"A meticulously crafted biography. . . . [Paul Laurence Dunbar is a] thorough and eminently readable account of Black genius." — Omari Weekes, Vulture

"A detailed, empathetic biography of African American writer Paul Laurence Dunbar. . . . Jarrett offers astute readings of all of Dunbar’s works. . . . Impressive

No responses yet