Like Princeton students since time immemorial, Mia Rosini ’21 entered her senior year looking for a job.

Employers, no less than flowers, bloom in certain seasons. The investment banks recruit earliest, usually in the spring of junior year, or even sophomore year for summer internships that often lead to offers of employment upon graduation. Consulting firms and tech companies schedule their interviews with seniors in September and early October. Nonprofits tend to hire later. Rosini knew she wanted to work in consulting and began meeting virtually with Princeton’s Center for Career Development as soon as school started last fall to research firms, update her résumé, draft cover letters, and prepare for interviews.

A lot of potential employers were interested. Rosini is the kind of applicant most recruiters crave: a concentration in the School of Public and International Affairs with a certificate in statistics and machine learning. Her junior paper won an award for outstanding independent research. She was also captain of the women’s squash team.

In previous years, Rosini might have had a job offer in her pocket before senior year even started. She had internships lined up last summer but, like a lot of other juniors, saw them disappear after COVID hit. The Career Development staff stepped in and appealed to the vast Princeton alumni network for help. More than 100 alumni stepped up with more than 300 internship opportunities, and Rosini got two of them — one unpaid and another for which she was paid by the University.

Though they weren’t exactly what Rosini thought she wanted to do, she was in no position to quibble, and over the course of the summer she discovered that she liked data science and government consulting. And after several rounds of interviews with a number of firms this fall, Rosini’s phone rang one morning in January with a job offer. Starting in August, she will be a data analyst for Booz Allen Hamilton.

If Rosini’s road to employment seems familiar, it was different from other years in one overarching respect: Due to COVID, she did everything virtually, from research to counseling to interviewing. For Zoom calls, she created an attractive background in her bedroom at home outside Philadelphia, propped her laptop on a stack of books so the camera would be at eye level, and put a sign on her door so she wouldn’t be interrupted. And, yes, she did dress up, just as she would have had she been interviewing in person. Still, Rosini has never met in person any of the people she will be working with and will embark on her new career remotely until Booz Allen’s Washington, D.C., office reopens at a date to be determined.

The Center for Career Development has undergone a virtual makeover itself, but one that, in many respects, was already underway. Necessity being the mother of invention, COVID forced Career Development to move all of its activities online, and this continued even after students returned to campus in February. “It has been a busy year,” says Kimberly Betz, the center’s executive director, with a sigh.

Busy, certainly, but not nearly as bad as many feared it might be. Although the national unemployment rate spiked to 14.8 percent in April 2020, just as seniors were turning in their theses, it has declined steadily since then, to 5.8 percent in June. According to a survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, businesses expect to hire 7.2 percent more Class of 2021 graduates than they hired from the Class of 2020.

From a placement standpoint, most of last year’s graduates weathered the disruptions of COVID pretty well, although Betz is quick to emphasize that this doesn’t mean no one saw an offer disappear or had trouble finding a job. Statistics suggest that the Class of 2020 did have more difficulty than its immediate predecessors. As of December, 65.6 percent of the Class of 2020 reported that they had found full-time employment, down from 72.3 percent of the Class of 2019 six months after their graduation. But apples-to-apples comparisons between classes are complicated since Career Development usually gathers its data on post-graduation plans at the Senior Checkout event, which has not been held the last two years and, as a consequence, the survey response rate last year fell sharply. (The number of students attending graduate school was also up slightly last year, but this may not be COVID-related since many application deadlines had passed before the pandemic began.)

Because some employers, especially banking and consulting firms, hire early, a lot of seniors had job offers when COVID hit. Many had their start dates deferred or were told to work remotely, but they kept their jobs. Firms learned a lesson from the Great Recession of 2008, Betz notes, when they cut recruiting and then were caught short as the economy recovered. To avoid repeating that mistake, those who could do so decided to continue recruiting, hoping to ride out the slump, and that bet seems to have paid off.

From a placement standpoint, most of last year’s graduates weathered the disruptions of COVID pretty well, although Betz is quick to emphasize that this doesn’t mean no one saw an offer disappear or had trouble finding a job.

“The important aspect of the pandemic recession is that it is so uneven. Those who are typically disadvantaged were even more disadvantaged,” observes Hannes Schwandt, a visiting fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, who studies labor markets. From an employment standpoint, this has meant that unskilled workers and those in sectors particularly hard hit by the lockdowns, such as hospitality and travel, suffered greater job losses. Other sectors, however, including those tech, finance, and consulting firms favored by many Princeton graduates, were hardly hit at all, Schwandt notes.

This suggests that highly skilled workers will not suffer the same short- or long-term losses in wealth that often plague students who graduate into a recession — and neither will their employers. News reports earlier this year showed that billionaires, including tech moguls such as Jeff Bezos ’86 and Elon Musk, added $1 trillion to their total wealth since the pandemic began. The extent to which this exacerbates the already yawning chasm of income inequality in America is another question.

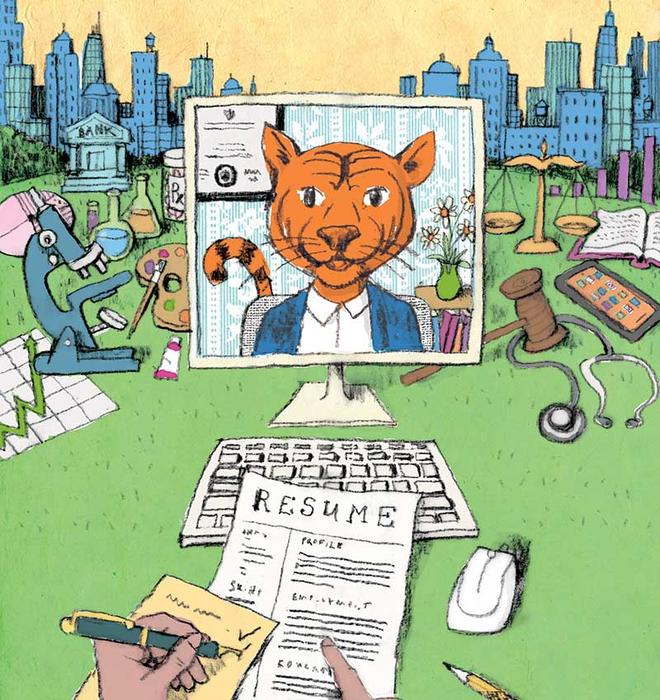

Since March 2020, when Princeton sent students home, Career Development offices in the U-Store building have remained closed as everything — from advising to résumé workshops to interviews and even job fairs — is done remotely. Rather than cancel large recruiting events such as the HireTigers Career Fair, which would ordinarily be held in Dillon Gym, staff members moved these events, too, into cyberspace.

All students receive an account on Handshake, an online platform where they can schedule counseling sessions; look for job postings, upcoming interviews, or information sessions; and review career guides. To focus their searches, Career Development asks students to list, for example, the kind of job they want (full, part-time, or internship), geographic preference, field, and size of company, and any particular traits they seek in an employer, such as a flexible work schedule or a commitment to social responsibility. Students can also list specific skills they offer, relevant classes they have taken, outside interests, and grade-point average.

The Career Development office makes extensive use of the limitless resource that is Princeton’s alumni body. A feature on the center’s website called Career Compass contains profiles of hundreds of alumni discussing their backgrounds, their undergraduate experiences, their jobs and how they got them, and lessons they have learned. Among other things, Betz says, it serves to remind current students that their field of study does not restrict the range of jobs they might later consider. Another networking opportunity, “Career Chats,” enables students to sign up for half-hour one-on-one calls with alumni in their field of interest.

Today’s students, who are used to doing things online, have readily adapted.

Christina Hain ’21, an operations research and financial engineering major, started interviewing in September after a virtual junior summer internship with the defense contractor Raytheon. She knew that she wanted to work in engineering or computers but was not sure where. “I sort of threw my résumé at anything that was out there,” she says, at the same time applying to graduate programs in computer science. Working with Career Development, however, helped her to winnow the list of potential employers, especially in consulting firms, many of which have longstanding recruiting ties to Princeton. It also helped her connect with an alum who told Hain that while her company wasn’t hiring, her husband’s was. Taking that tip, Hain applied to Keystone Strategy, a consulting firm in Boston, went through several rounds of virtual interviews, and shortly before Christmas, received an offer. Not long after, she was also admitted to two master’s degree programs. For now she has deferred them and taken the job, starting remotely in August.

The students who were most adversely affected by COVID were not last year’s seniors but juniors in the Class of 2021 who lost internships that often lead to permanent job offers. Betz and the Career Development staff spent much of the spring of 2020 scrambling to contact Princeton’s alumni network in hopes of filling that void.

Logan Sander ’18 was one of dozens who responded. Midstory, a nonprofit she co-founded with Samuel Chang ’16 and Ruth Chang ’12, tries to draw attention to issues affecting smaller cities such as Toledo, Ohio — places that Sander acknowledges rarely appear on the radar of job-seeking Princeton students. Their internship application deadline had already passed when Betz reached out, but Midstory decided to reopen it. “We all had such an incredible experience at Princeton, and this was the best way we thought we could give back,” Sander explains. Within weeks, Midstory hired eight Princetonians — including sophomores, juniors, seniors, and even a recent graduate — as interns.

Since none of the interns were able to spend any time in Toledo, Sander arranged a virtual walking tour of the city on Google Maps and hosted Zoom social hours and a talent show to build team spirit. By the end of the summer, she says, “all of them remarked that although they had never set foot in Toledo, they felt intimately tied to it.” This year’s Midstory internship program will also be virtual, and the nonprofit has fielded its largest and most diverse applicant pool ever.

In a few cases, those emergency internships last summer led to permanent job offers.

Black Sheep Foods, a San Francisco startup developing plant-based alternatives to meat, is not a place that ordinarily hired summer interns. “It wouldn’t have been on our radar had we not gotten an email,” admits Lauren Whatley ’11, who heads the company’s marketing team. Largely on her recommendation, Black Sheep brought in six Princeton interns. “Career Development has just made it so easy to coordinate this internship process,” Whatley says.

Not only were her colleagues impressed by the students’ talent, but the internships helped Black Sheep make a connection to Princeton and identify other promising potential applicants. Although Black Sheep had no intention of hiring when the summer started, two of those Princeton interns, in fact, received permanent job offers.

One of them was Alice Wistar ’20 who was, in a sense, a poster student for the disruption of COVID. A Spanish major, she had applied for a few fellowships through the Princeton in Latin America program, though she was not selected. Facing unemployment last April and feeling “down in the dumps,” she signed up for a four-week program through Career Development to polish her résumé and sent out some applications when she saw the posting for a Black Sheep Foods internship.

As luck would have it, a virtual part-time Princeton fellowship opened up just as she was graduating. Wistar drove out to Berkeley to spend the summer with her cousin, planning to juggle the fellowship, the paid Black Sheep internship, and some tutoring she took on to make extra money, but she found that she was passionate about the connection between food and climate change and that she liked working at the small startup. When her internship concluded last November, Black Sheep offered to make her one of only seven full-time employees. She has been working there since February, doing everything from marketing to patent applications, and says, “Honestly, I would do this for free.”

Though students in many fields fared well despite some anxious days last spring, seniors aspiring to careers in the arts faced an especially difficult time. Pilar Castro-Kiltz ’10 founded Princeton Arts Alumni, which helps artists in all fields network and support each other’s projects. The group has always been busy, she notes, but COVID has put it “in overdrive.” This past winter, for example, Princeton Arts Alumni hosted an online variety show, posting Venmo handles for each performer — a virtual way of passing the hat.

Anecdotally, Castro-Kiltz says that some types of job postings in the arts seem to be increasing this spring, especially in marketing and strategy. “In contrast,” she points out, “there haven’t been any off-Broadway auditions.” Worse, many of the so-called “survival jobs” such as bartending or waiting tables, which aspiring artists rely on while working for their big break, also disappeared for much of the past year, though they are now returning as the economy reopens. Many artists have turned to other jobs such as tutoring, childcare, or fitness instruction to make ends meet. The already steep path to a remunerative career in the arts will most likely remain steep for the foreseeable future.

Will changes to the placement process be permanent? The Center for Career Development seems to be planning as if much of it will be.

Many companies are likely to continue conducting first-round interviews virtually rather than in person; they are cheaper and enable employers to reach a broader range of schools and students. Even before COVID, Career Development was allowing students to book rooms for phone or video interviews. They have since equipped six of their 15 interview rooms with complete video, audio, and display capabilities.

In a virtual world, it is also easier for students to search on their own through internet jobs sites such as Indeed and ZipRecruiter. Nevertheless, Career Development will continue to play an important role by insisting, for example, that employers not discriminate, that they follow through on appointments, and that they give students sufficient time to consider any offers before having to accept them. “Our job is to advocate for the students,” Betz says.

Students will come back to campus in the fall, but will recruiters? Can they? “There probably won’t be a huge jobs fair at Dillon Gym, at least in the fall,” Betz predicts, “but I’m betting that there will still be a [virtual] jobs fair. Last year, people really weren’t sure how we would handle this. Now we’re doing it. We know better how to deal with a virtual workplace.”

Not everyone, of course, has figured out what they want to do with their life by the time senior spring rolls around — thank goodness. While many seniors target six-figure starting salaries on Wall Street or burn to become the next Jeff Bezos, there are also students like Julia Walton ’21 in every class.

Walton majored in English and received certificates in creative writing, East Asian studies, and humanistic studies. She won departmental prizes as a sophomore and junior, was editor of the Nassau Literary Review, and served as student representative on Princeton Arts Alumni. She, too, would be a perfect hire. Walton thought about applying to Ph.D. programs in English or comparative literature but notes that the teaching market is terrible and that many graduate schools are cutting admissions so they can support students who are already enrolled. “I sent a bunch of applications to nonprofits but none panned out,” she continues. She is now looking at academic fellowships or, ideally, a job in the publishing industry.

Throughout the spring, Walton met with the staff at Career Development to polish her résumé. She continues to receive email notices whenever a company that might interest her is interviewing, and she has also reached out to alumni through LinkedIn. Like many, Walton is ambivalent about the “new normal” of virtual recruiting but recognizes that, for now, there is no other choice. “It’s nice where you can meet in person and see their offices,” she notes, “but people have been pretty flexible.”

As Commencement approached, Walton knew that she, too, had to be flexible. It may take her a while to find her niche, but if she doesn’t get any nibbles from publishing houses soon, she will think of something else.

“I’d say my mood is ... well, a little bit mixed,” Walton writes in a follow-up email. “Maybe a little nervous, and a little envious of people who know what they’re doing. But mainly I’m withholding judgment, since it’s so hard to know what’s ahead.”

“Everyone tends to say ... that tons of people graduate without jobs and that there are great opportunities out there if you’re open to them, which is reassuring,” she reasons. “So maybe I’m what you’d call ambivalent — but it’s more that I’m trying to keep a realistic perspective. I have a feeling that it will all turn out OK, wherever I end up.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

2 Responses

Mike Giftos ’92

4 Years AgoCareer Paths for Essential Workers

The homophones “higher” and “hire” in the July/August issue (“What’s Next for Higher Ed?” and “Hire the Tiger”) underscore the similar sound but discordant direction Princeton has taken during COVID. When the higher-ed article on COVID and universities quoted President Eisgruber ’83 claiming it is a “moral responsibility” to now return to in-person teaching, and in the next article on hiring Tigers I learned that during COVID Princeton undergrads were able to successfully secure investment banking, consulting, and tech jobs, I started to wonder where exactly Princeton’s moral compass is pointing these days.

While Princeton was following CDC guidelines and public-health emergency declarations when they taught classes remotely and conducted career fairs and job interviews via Zoom technology, the term “moral responsibility” seems a bit elevated and out of sync with the COVID experience of many other parts of society. We have always expected firefighters, policemen and policewomen, and paramedics to immediately respond to 911 calls in the face of danger and uncertain circumstances. At the onset of the COVID pandemic we all expected doctors, nurses, and other health-care workers to continue caring for sick patients even in the face of inadequate protective equipment and no COVID vaccine. What would happen to our society if firefighters only responded to alarms when the smoke cleared? Or if the most talented and smartest college graduates sought “essential-worker” professions instead of lucrative remote jobs?

Maria S. Picone ’08

4 Years AgoWorking With Princeterns

I was surprised and pleased to see Julia Walton ’21 featured in “Hire the Tiger” (July/August issue). As part of an outreach initiative, the Center for Career Development asked alumni with openings in their organizations to advertise internships. At Chestnut Review, the literary magazine for which I work, I advocated for positions to be created, and we ultimately selected Julia as one of three “Princeterns.” She has been a force in our small organization, and I believe she will be a great hire. I graduated in 2008 and struggled to make my way for years in the job market, so it’s been a pleasure to extend growth opportunities to other Princetonians. I also hope to model unconventional success as a first-gen college student who struggled mightily during my undergrad years and didn’t have a clear picture of what my afterwards would look like, let alone in the broader context of the Great Recession.