History: Cancer, color, culture

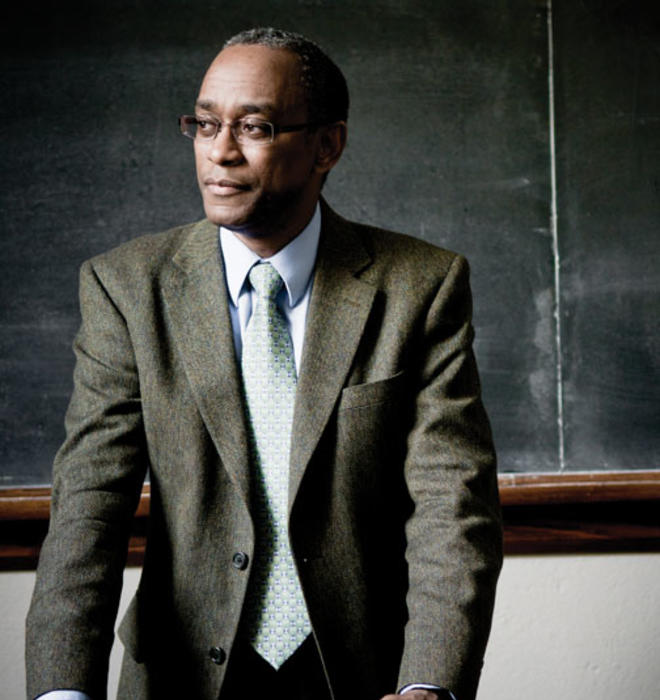

In medicine, statistics don’t tell the whole story – Keith Wailoo adds history to the mix

Music lovers of a certain age surely remember Minnie Riperton as a soul and pop singer with an extraordinary voice that could flutter up and down five-and-a-half octaves. Keith Wailoo remembers her as someone else: the first black woman in the United States to receive national attention as a cancer victim. When she died in 1979, it was evidence that cancer — viewed for decades as a white woman’s disease — had crossed the color line.

Why had the egalitarian nature of cancer eluded scientists and policymakers for so many years? Statistics told one story; Wailoo, a Princeton professor of history and public affairs, tells another. “To truly understand how cancer crossed the color line, you need to step back and to consider ... broader social trends shaping cancer awareness,” he says.

And so for the last several years, Wailoo, now 48, has worked to present a picture of cancer beyond the numbers, first combing through medical literature, life-insurance records, government documents, and the files of physicians and cancer organizations. Then he focused on depictions of cancer in the mass media, where he saw how for a century, the war on cancer was viewed through a lens of race and gender. Cancer was seen as a “disease of civilization” that affected stressed, modern white women. African-Americans, on the other hand, were pictured as “a homogeneous group that was carefree and protected from cancer,” Wailoo writes in his new book, How Cancer Crossed the Color Line, “living as they did in ‘primitive’ stress-free environments that made them less vulnerable to the modern scourge.”

When Riperton became a symbol of cancer, black women understood that the disease was one more concern about which they, too, needed to be aware.

Through his work on cancer and on topics like the politics of pain, organ donation, and genetic diseases, Wailoo is changing the way scholars think about the influence of societal norms on medicine, a discipline so often perceived as being driven strictly by reliable data. His research on the history of illnesses — and the medical establishment’s response to disease — illuminates not only changes in medicine and science, but social and cultural changes as well. “We often tend to think of medicine as value-free, that it’s neutral and should be the same regardless of who we are, but in fact it’s deeply reflective of underlying social values and norms,” observes Elizabeth Armstrong, a Princeton professor of sociology and public affairs.

Wailoo’s classes at Princeton, where he arrived in 2010, tackle topics such as the history of drugs, with medical and public opinion swinging between the belief that drugs are “a kind of panacea” to “intense skepticism” that they do much good. “For instance, [consider] the rise and fall of hormone-replacement therapy,” he offers as an example. “There’s an appeal associated with these novel ways of treating women’s ailments. Then there’s an anxiety about the side effects associated with these innovations. ... There’s a rise and fall and rejection and infatuation with different drugs.” He aims to teach his students to “be in a position to ask thoughtful, detailed, and nuanced questions about how we got where we are.”

In his classes and his research, Wailoo rejects the obvious path. He raises questions about the common assumption that statistics are correct, showing instead how they can reflect difficulties in gathering data or be complicated by racial categories that have changed over the years (for example, Americans who identified themselves as belonging to one minority group in the past might now say that they are multiracial).

Many Americans, hearing of a book about race and medicine, would think immediately about the infamous Tuskegee study in which syphilis-infected black men were studied but were not told that they had the disease or treated for it. Wailoo’s work tends to focus on social processes involving race, not on overt racism. “He asks questions that most people don’t ask when they explore issues surrounding the conceptualization of disease and treatments and health care,” says Princeton anthropology professor Carolyn Rouse. “Race is in many ways central to his work, yet he never treats it as a kind of simple question of racism.”

Wailoo’s interests in race and identity were shaped early. He immigrated to the United States with his family as a child from Guyana, and grew up in New York City before finishing high school in New Jersey. “Moving around as much from place to place as I did meant always adjusting and readjusting my sense of who I was — provoking questions of identity quite apart from the normal issues youngsters tackle as they grow up,” he says. His last name is Indian, he notes, a fact that was important in Guyana. In the United States, however, “I was and am identified, first and foremost, as black. ... You could say this kind of experience got me interested in identity — how it is formed, how it changes.”

At Yale he earned a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering, but by the time he graduated he realized he was less interested in the technical aspects of his field than in “the implications of these chemical processes for things like producing acid rain, fuel efficiency, issues having to do with the dependence on foreign fuels.” In other words, he most wanted to understand the societal repercussions of science.

At the time the study of history and sociology of science was growing in popularity, thanks largely to the work of Charles Rosenberg, a historian at Penn who wrote a groundbreaking book on the history of the cholera epidemic in 19th-century New York City. Rosenberg studied the history of medical ideas, and his book The Cholera Years, regarded as a seminal piece of work that has informed generations of scholarship on disease, changed Wailoo’s thinking. “It was a classic study of the way in which how a society understands and how a society intervenes against disease can teach you a great deal about medical and public-health theories,” Wailoo explains. “It also explores the origins of disease in social inequalities. It is a history that can educate readers about society at large.” Wailoo wanted to follow on the same path, and earned his Ph.D. in history under Rosenberg at Penn.

“For some people, yes, medicine exists in the world of the sciences,” but for others, Wailoo says, “the world of medicine is where questions about science intersect with issues of humanity, culture, values, politics, and economics.”

Eventually, Wailoo wound up teaching in the medical school at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in the Department of Social Medicine, which brought together physicians, medical economists, social scientists, and historians. There, in the 1990s, he encouraged medical students to broaden their approach to disease. For example, tuberculosis, a disease commonly associated with 19th-century romantic heroines, was on the rise at the time, and the students were focusing their discussion on the role of antibiotics. “I pointed out that the decline of tuberculosis in the early 20th century had already begun before antibiotics, due to developments in sanitation and hygiene,” he recalls. The lesson for the future doctors was to avoid basing their diagnoses and treatments solely on what was popular or in the spotlight.

Wailoo remained in North Carolina for nine years, before moving to Rutgers University as a history professor and later becoming the founding director of Rutgers’ Center for Race and Ethnicity. His time in Chapel Hill had an immense impact: “It was really by teaching in the South that I became interested in how one explores the intersections of race and medicine,” he says.

Building on his experiences in North Carolina, Wailoo identified four major contemporary issues in American medicine that he felt could benefit from his brand of historical and sociological analysis: genetics, transplantation and vaccination, cancer, and his current research topic — pain. In 1999, he received the $1 million James S. McDonnell Centennial Fellowship in the History of Science to examine the history of the biomedical sciences and their social, cultural, and political implications. Over the next decade, he would go on to write and co-edit books on topics including the politics of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, organ donation, and genetic medicine — each time, showing the social considerations that shaped policies and debates.

When he received the McDonnell fellowship, he just had finished Dying in the City of the Blues (University of North Carolina Press, 2000), which explored sickle cell anemia, a genetic disease that primarily affects African-Americans, in Memphis. Dying broached the reluctance of some Memphis doctors to prescribe painkilling drugs to black patients, because the doctors suspected some healthy patients were feigning symptoms in order to obtain drugs.

Wailoo showed how societal factors were influencing the diagnosis and treatment of sickle cell, as doctors failed to assess patients purely on their symptoms. And as a result, Wailoo argued, statistics relating to sickle cell were suspect.

Later came A Death Retold: Jesica Santillan, the Bungled Transplant, and Paradoxes of Medical Citizenship (University of North Carolina Press, 2006). The book, which Wailoo co-edited, is a collection of essays that center on the 2003 case of an undocumented immigrant girl, Jesica Santillan, who had received a heart-lung transplant of the wrong blood type, a grievous medical error. The case prompted a debate about immigration, the surprisingly high number of medical errors, and the inequities in health care afforded to those who have money and those who don’t.

A Death Retold confronted the widespread belief that illegal immigrants are a drain on the health-care system, particularly on the transplantation program. In fact, in terms of border-crossing for transplants, American citizens are far more likely to take advantage of the availability of organs in other countries. Here at home, immigrants donate more organs for transplantation than they receive. The book was seen as a morality tale.

How Cancer Crossed the Color Line, published in January by Oxford University Press, spans a century, showing how doctors’ early focus on white women — largely ignoring African-Americans — was not a reflection of who actually had the disease, but of who was most commonly diagnosed. The tools of the time were nowhere near as sophisticated as what’s available now, and women’s cancers (i.e., breast, ovarian and cervical) “were the easiest to diagnose, given the diagnostic ability of the time,” Wailoo says. The media informed well-off white women that they could avoid cancer by bearing children (but not too many) and nursing them. Safeguarding these white women’s reproductive organs became an essential aspect of the war on cancer — notably, a goal shared by leaders of the eugenics movement of the period.

In time, though, conditions changed. The life expectancy of poor Americans increased, and black Americans were more likely to live to the age when cancer was more common. New diagnostic tools brought fresh attention to cancers that affected men. As blacks migrated from the rural South to the urban North in the early 1920s, they were more likely to be seen by doctors with better tools, leading to a rise in reported cancer among blacks. And so post-World War II America saw a new push to consider cancer as an equal-opportunity killer. By the early 1970s, researchers began to ask why cancer mortality seemed to be rising faster among blacks than among whites.

At the end of his book on cancer, Wailoo returns to Riperton. Why, he asks, “does it matter how cancer and race are personified on the public stage?” He goes on to answer his own question: “The story of cancer and the color line ... becomes the story of cancer’s transformation and of racialization — by which I mean, the processes by which scientists used the disease to create narratives of difference.” And while imagined differences prevalent at the turn of the century have been discredited, he notes, they were authoritative and influential at the time — and they determined how money would be spent on advocacy, diagnosis, and treatment.

Similar policy debates take place today, and Wailoo — who is as calm and deliberate in his public writing as he is in his scholarly work — aims to provide history and nuance to those discussions. He contributed to a 2006 report by the Institute of Medicine, a policy advisory group, about whether there should be financial incentives for organ donations, to increase the availability of organs. (Wailoo explained the program’s historical basis in altruistic giving, and the group advised against the incentives.) He also has added his voice to the national debate on health care, focusing on the topic of his most recent work: the history and politics of pain relief. Noting in The American Prospect in August that pain relief historically has been politically contentious — there’s an “epic tension between Americans’ desire for compassionate care and relief and their fears of drugs and dependency” — Wailoo lamented that a bipartisan move toward comprehensive pain care had grown far less ambitious.

The point, Wailoo says, is that people must know a policy’s past — in all its complexity — to understand what’s happening today. History matters. As he told his UNC medical students: “The history of medicine is defined by a variety of paths that were not taken, and we can ask questions about paths not taken. Asking them helps us realize that the path going forward is open to multiple possibilities.”

Maya Rock ’02 is a freelance writer and editor in New York City.

No responses yet