Hitting the High Notes

Countertenors Anthony Roth Costanzo ’04 and Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen ’15 lead an operatic revival

“Pur Ti Miro,” soprano Sarah Shafer sings in the closing duet of Claudio Monteverdi’s 1643 opera, The Coronation of Poppea. “I adore you.”

“Pur ti godo” — “I desire you” — Anthony Roth Costanzo ’04 answers, his crystalline countertenor almost as high.

“Pur ti stringo.” “Pur t’annodo.” “I embrace you. I enchain you,” the two characters, Poppea and Nero, seduce each other in Italian, the delicate Baroque harmonies intertwining. It is one of the most sensual duets in all of opera.

Standing with the rest of the cast on the stage is Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen ’15, a countertenor who plays the role of Ottone. Like Costanzo, he knows Poppea well; it is part of the countertenor repertoire, and both sang it as Princeton undergraduates. As he does at the end of each performance during the opera’s 10-day run in June at Cincinnati’s Corbett Theater, Nussbaum Cohen picks a small section of the audience and watches.

“Si, mio ben, si, mio cor, mia vita, si, si, si, si. ...” (“Yes, my love, yes, my heart, my life, yes, yes, yes, yes. …”)

Countertenors Anthony Roth Costanzo ’04, above left, as Nero, and Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen ’15, kneeling, as Ottone, perform with other cast members in the Cincinnati Opera’s production of Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppea, in June.

As the last notes fade and the lovers raise their arms in ecstasy, Costanzo’s right hand grips a dagger. High on the coronation platform, he turns as if to embrace Poppea — but stabs her instead. She falls back, dead. The stage goes dark. After a moment, the house erupts. Nussbaum Cohen catches it all.

“I always like to watch [the audience’s] reaction,” he says. “There are always gasps.”

Gasps indeed — because Nero killing Poppea is not how the opera is supposed to end.

COSTANZO AND director Zack Winokur, old friends, batted around the surprise finale during a long walk shortly before production began. Not only was it dramatically jolting, it seemed truer to the spirit of the characters. Monteverdi let the historical Nero off easy; the Roman emperor did, in fact, kill Poppea and their unborn child a few years after the coronation. Although they ran their plan by the rest of the cast, director and star went back and forth about executing it, putting it in some rehearsals and taking it out, until opening night.

Monkeying with Monteverdi is the sort of risk — career defining, perhaps — that only an established artist can take. Costanzo fits that bill. Still, this is a good time to be a countertenor. Ignored for generations by composers and producers, countertenors now sing new music written just for them, and long-neglected operas are being revived to showcase their unique vocal range. Last year, countertenor Iestyn Davies won raves on Broadway in the play Farinelli and the King.

Even countertenors acknowledge how incongruous it can sound for an adult male singer to open his mouth and let out such high notes. Countertenors sing at the same range as a female soprano or mezzo soprano, or as a boy soprano or alto. With eyes closed, it can be difficult to tell the male and female singers apart.

VIDEO: Anthony Roth Costanzo ’04 performs “L’invitation au Voyage”

Courtesy WQXR

“I love that, because I find that it really draws people in,” says Nussbaum Cohen, who won the Metropolitan Opera’s prestigious National Council Auditions Grand Finals last year. “For people who aren’t ‘opera people,’ there is something about hearing a countertenor for the first time that’s beguiling.”

It is a special singing technique that creates a sound that differs from the countertenor’s normal singing or speaking voice. Both Costanzo and Nussbaum Cohen are natural baritones. Many male singers can reach the falsetto register that characterizes the countertenor; what makes a countertenor unique is that he can sustain it and sing expressively.

From a technical standpoint, countertenors produce that mesmerizing sound by vibrating only the tips of the vocal cords. When a tenor sings, 70 percent of his vocal cords close; when a countertenor sings, only about 10 percent close. Not surprisingly, it requires technical precision for a countertenor to generate power and volume. Basses might sound even richer after a night on the town and a few cigarettes, but the countertenor voice can be a delicate instrument. Nussbaum Cohen, for example, avoids alcohol, dairy, gluten, and even spicy foods lest they irritate his vocal cords.

VIDEO: Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen ’15 performs “Dawn, Still Darkness” from Dove's Flight

Courtesy Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen

The countertenor repertoire largely consists of works written before 1750 and after 1950, but they were long overshadowed by an even more exotic sound. Monteverdi wrote the parts of Nero and Ottone for castrati, male singers who had been castrated before puberty to preserve their unbroken voices and who could sing even higher than a countertenor. Castrati were among the most famous singers of their time, and because audiences wanted to hear them, composers wrote for them. Baroque opera is filled with castrati roles. In another surprise to modern sensibilities, they often played heroes, kings, and villains, parts we might expect to be more deep-voiced.

Musical tastes changed in the Romantic period, explains Professor Wendy Heller of Princeton’s music department. Mozart and others began to write operas that were less florid and more naturalistic, turning away from the biblical and classical themes that had been Baroque staples. As the subject matter became lighter, ironically, the male voices became deeper. Verdi, Wagner, and the great operatic composers of the 19th and early 20th centuries wrote most of their male leads for tenors. They aren’t making castrati anymore — thank goodness — although the last one did not retire from the Vatican choir until 1913. Even so, the male falsetto never really died out, living on where it began in Catholic (and later, Anglican) church music. In pop culture, it can be heard in the trills of Frankie Valli and Michael Jackson, Prince and the Bee Gees, and even in Hank Williams’ cowboy yodels. Countertenors don’t sound quite the same as castrati did, but they are our closest approximation.

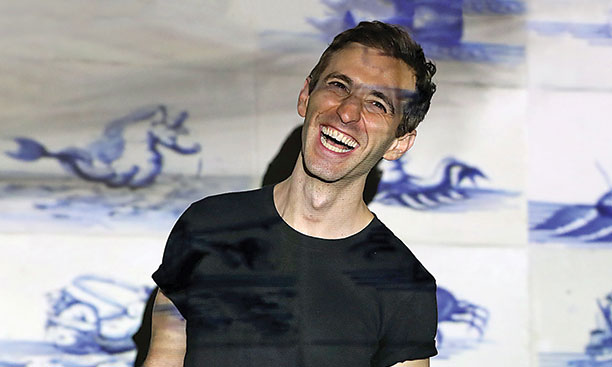

THEIR SHORT RUN in Poppea was a welcome opportunity for Princeton’s two countertenors to work together. Beyond their shared ability to sing in a range few men can sustain, a Princeton education, winning the Met competition, and a similar monogram, Costanzo and Nussbaum Cohen do not seem to have much in common. Nussbaum Cohen is tall and broad-shouldered, with an engaging, boyish enthusiasm. Costanzo is small and slender. A boundary pusher, he once appeared on stage nude in Philip Glass’ opera Akhnaten.

The two men also entered their careers from different directions. Costanzo has been on stage nearly his entire life. The son of two Duke University psychologists, he appeared in his first theatrical production at the age of 8. By 11, he had an agent, and he later appeared on Broadway and in several national touring companies. In high school, he was nominated for an Independent Spirit award for his role in the 1998 Merchant Ivory film, A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries.

When he was in eighth grade, Costanzo appeared in his first opera, a New Jersey Opera Festival setting of the Henry James novella The Turn of the Screw. He was struck by how complex and layered operatic stories were, and how he could engage those stories both singing and acting. It was in The Turn of the Screw that he met the show’s director, Michael Pratt, who also conducts the Princeton University Orchestra and directs the program in musical performance. Costanzo chose Princeton in large part because of his relationship with Pratt, who promised to work with him on a major project every year. He was also able to sing professionally and recalls taking his freshman finals in Italy while appearing at the Spoleto festival. For his senior thesis, Costanzo wrote a show about a fictional 18th-century castrato and performed it in Richardson Auditorium, raising a budget of $35,000. Filmmaker James Ivory, a friend, designed the costumes.

Three years after winning the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions in 2009, Costanzo earned first place in Placido Domingo’s world opera competition. Since then, he has appeared on stages around the world and gained renown for a voice The Wall Street Journal called “otherworldly.”

NUSSBAUM COHEN, on the other hand, describes his decision to pursue a career in opera as more of an accident.

He entered college as an aspiring Woodrow Wilson School major and sang in the Glee Club and chamber choir. In the winter of his freshman year, Nussbaum Cohen won a ticket lottery in the music department to see a production of La Bohème at the Met. It was the first opera he had ever seen and, transfixed, he decided to dedicate himself more seriously to singing.

The full story, though, is a little more nuanced than that. When he was in seventh grade, a friend’s mother heard him humming and urged his parents to get him music lessons. Nussbaum Cohen sang in the Brooklyn Youth Chorus throughout high school and remained a boy alto even after his voice changed because it was the only way he knew how to sing.

He sang in his synagogue’s services at Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and spent the summer after his freshman year of high school learning the musical style of the Jewish prayer service, so he could serve as the second cantor. “For me, it was about conveying both the meaning of the words and the musical lineage,” Nussbaum Cohen told an interviewer for the (Houston) Jewish Herald-Voice this year. “The Jewish people is intrinsically tied to this music. What a thing it is to serve that tradition!”

By the time Nussbaum Cohen applied to Princeton, he had the makings of a rich and expressive countertenor. Gabriel Crouch, the director of choral activities, recalls being astounded by an audition tape Nussbaum Cohen submitted with his application: “I said to myself, ‘My goodness, what is this voice?’ ” When Nussbaum Cohen appeared for his live audition several weeks later, Crouch called in colleagues so they could hear him, too.

That voice also impressed David Kellet, a member of the performance faculty who became Nussbaum Cohen’s vocal coach. “When I first heard him, my mouth hung open,” he says. “Aryeh’s instrument is of a size and richness that is unique.”

Even as he pursued his singing, Nussbaum Cohen declined to pigeonhole himself as a musician. He ran unsuccessfully for class president; founded the Princeton chapter of J Street, a progressive alternative to the pro-Israel lobbying group AIPAC; and co-founded a Muslim-Jewish dialogue group. He graduated with a degree in history and certificates in vocal performance and Judaic studies.

VIDEO: A September 2011 master class included an early interaction between Costanzo and Nussbaum Cohen

The real turning point came at the end of his sophomore year when Nussbaum Cohen received a Martin A. Dale ’53 Summer Award, which enables students to pursue projects outside their regular course of study. Nussbaum Cohen titled his application “An Opportunity for Operatic Growth.” With the grant, he approached Costanzo, whom he had met at campus music events, and asked him for lessons. For a few months that summer, Costanzo tutored Nussbaum Cohen on fine points of technique and introduced him to some of his teachers and coaches.

“Anthony played a huge role in opening my eyes to the wonders of the art form, and I am eternally grateful,” Nussbaum Cohen says. Costanzo returns the compliment: “Aryeh is incredibly talented, eager, and has a fantastic instrument. I’ve been excited to see his development.”

Between lessons with Costanzo, Nussbaum Cohen used his grant to attend Baroque music programs at Oberlin College and in Vancouver, where directors told him that he might be able to sing opera professionally. “My attitude was, if I don’t try now, I’ll probably always look back and wonder,” he says.

He spent the year after graduation “woodshedding” — practicing every day, working with voice coaches, and preparing for the Met competition. For his performance piece, he chose an aria from the 1998 opera Flight, the story of an Iranian refugee stranded at Charles de Gaulle Airport and trying to evade deportation. Friends and family filled Lincoln Center for the competition or followed along on social media. Although Nussbaum Cohen was one of six winners, New York Times classical music editor Zachary Woolfe ’06 declared, “[T]here was only one complete artist ... he clearly stood apart from the pack.”

Nussbaum Cohen followed that up by winning the Houston Grand Opera’s Eleanor McCollum Competition, which earned him a spot in the company’s young artists program. For the past year, he has received intensive training in everything a young opera singer needs to become a professional: voice lessons, movement lessons, acting lessons, language classes, and coaching sessions for musical and artistic preparation. Nussbaum Cohen supplemented this with hours of daily work at home, practicing, learning translations, and listening to recordings. One highlight of his year in Houston was performing as Nirenus in Handel’s Julius Caesar alongside Costanzo and countertenor David Daniels.

“You never have it figured out,” Nussbaum Cohen says. “That’s probably my favorite thing about this career I have stumbled into: You’re always a student. That keeps things interesting and fresh.”

Though it may seem surprising that Princeton’s music program has developed two successful operatic countertenors, Pratt credits Costanzo for setting things in motion. “When he won the Met auditions, well, word got around quickly about Princeton being early-music and opera friendly,” Pratt says. “Aryeh’s coming was thus not pure luck, but he is not the only fine countertenor to come through. And I hear that there are more on the way.”

SHORTLY AFTER Poppea ended, Nussbaum Cohen began an 18-month fellowship with the San Francisco Opera. During the upcoming season, he will appear around the country, but one project stands out. In April, he will sing the role of King David in a performance of Handel’s Saul at Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. Any parent would be proud, but in the Nussbaum Cohen family this engagement is special. “They say every Jewish mother wants her son to be a doctor,” his mother posted on Facebook. “Not me. I’m thrilled that my son will be King David.”

Grasping all of Constanzo’s projects is difficult, but a profile last year in the Times gives a flavor. It ran under the headline “Anthony Roth Costanzo Exists to Transform Opera.”

Costanzo left Cincinnati even before Poppea’s run ended (an understudy sang the last performance) to keep a commitment in Japan, where he collaborated with Kabuki and Noh performers to incorporate Baroque arias into the traditional Japanese story The Tale of Genji, at Tokyo’s Kabuki-za theater. Six years ago, Toyoshige Imai, a Kabuki playwright, saw Costanzo during a rehearsal of The Enchanted Island in New York. They became friends, and Imai suggested they collaborate on the new work, which premiered in Kyoto in 2015, with Costanzo singing Scarlatti and Dowland arias in Kabuki costume. All 26 performances sold out, and Costanzo found himself accosted by Japanese fans on the street.

This month, he will release his first solo album, which will coincide with the debut of Glass Handel, an “operatic art installation” at Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation. While Costanzo sings works by Handel and Philip Glass, a 21st-century minimalist, in costumes designed by Calvin Klein’s chief creative officer Raf Simons, artist George Condo will paint on a giant canvas in response to the music, ballet dancers choreographed by Tony Award winner Justin Peck will perform, and 10 filmmakers will shoot music videos that later will be shared online. The audience, meanwhile, will be wheeled to different parts of the art gallery on movable seats.

If this sounds over the top, Costanzo disagrees. “Opera is unique in that it was one of the first interdisciplinary art forms,” he points out. “Ballet began in opera. Costume design. Set design. Going forward, it can’t stay insular. It can’t be opera for people who already love opera. The way to break out of that is to take those disciplines and engage with them in a more creative way.”

Of course, there is also a practical side: The limited number of roles for them forces countertenors to be versatile. Though Costanzo doesn’t direct this last point to Nussbaum Cohen, it could be seen as a bit of brotherly advice.

“The opera houses aren’t even doing an opera you can be in every season,” Costanzo notes. “So you are forced to carve your own path instead of just waiting for the phone to ring. That is an asset in our era, where opera is not as much a part of the culture as it once was.

“Thinking creatively and making new opportunities,” he says, “not only for yourself but for the art form, is what allows for an interesting career.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

1 Response

David Bodenberg *58

7 Years AgoOperatic Tour de Force

Mark Bernstein's article "Hitting The High Notes" is absolutely mesmerizing. That PAW can produce such a piece in a weekly publication almost defies belief. All of us grads -- and I am not a musician -- are proud of you and grateful.

[Editor’s note: Though we greatly appreciate this comment, it gives us more credit than we deserve. PAW now comes out 14 times a year — we just can’t bring ourselves to change the magazine’s name.]