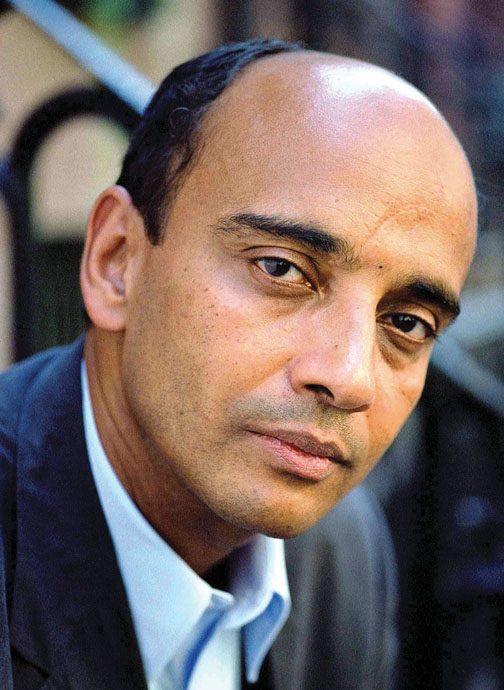

Philosophy professor Kwame Anthony Appiah is one of Princeton’s most distinguished public intellectuals. Raised in Ghana, educated in England, he jets around the globe giving lectures on how philosophical ideas apply to everyday life. The title of his previous book, Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, is suggestive of his far-reaching approach.

While writing that book, he became intrigued by the ancient Chinese practice of footbinding (crushing girls’ feet into a tiny size), which proved resistant to all moral appeals against it and disappeared only when national honor suddenly seemed at stake. Could honor be different from morality? From Aristotle on down, the two have been conflated, but could honor be the more powerful instrument in changing opinion about evil behaviors? Honing his thoughts through lectures at universities in England, Germany, Austria, and the United States, Appiah has produced The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen, published by Norton in September.

He singles out three historic practices that later were stamped out: dueling, footbinding, and the Atlantic slave trade. In each case, he says, a successful public campaign to end the misconduct was based not on questions of right or wrong, but on honor. Dueling swiftly perished when attitudes changed among gentlemen, who went from considering it highly honorable, to disreputable. The excruciating binding of women’s feet disappeared with great abruptness once China began to worry about its reputation among nations, early in the 20th century — national honor seeming at stake. A similar sense of honor led Great Britain finally to ban the slave trade after all appeals to morality had proven futile.

The book concludes with the problem of honor killings in today’s Pakistan, where parents sometimes kill daughters following sexual liaisons or rape. It’s estimated that as many as 1,000 women in Pakistan and 5,000 worldwide are murdered annually, according to the U.N. Population Fund. The effective way to stamp out this horrible practice, Appiah argues, is to stress to Pakistan that it is shameful and dishonorable, not that it is morally wrong.

His most important conclusion, Appiah told PAW, is that “honor is not part of morality; it can be aligned with it, or not. I think it’s more helpful to think of it as separate, and how you can adapt it to serve moral ends.” He notes that the Princeton honor code is not entirely about morality; in part it “reinforces norms that are purely academic, like sourcing and acknowledgments. You don’t have an obligation to write footnotes in your personal letters.”

No responses yet