Telling Sarah Palin jokes at a comedy show in Washington, D.C.’s Adams-Morgan section the night before the Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert rally last October is like shooting fish in a barrel. With a bazooka. The targets are at point-blank range and hardly worth the trouble, while the audience is ravenous. But before Jeff Kreisler ’95 can nudge the crowd of liberals toward the broader point he wants to make, he tosses them some easy ones.

“We live in a stupid, stupid age of American politics,” he mutters, pacing the stage in a button-down shirt and jeans while sipping a can of Yuengling. “But I’m excited by it. I’ve always been into politics, and I think it’s perfect because even the word ‘politics’ describes what’s going on right now. Politics. Poly-tics. Poly-ticks. Many bloodsuckers.”

OK, that one gets only a titter, and Kreisler, who in addition to doing his own set is acting as emcee for a show that includes fellow alum Adam Ruben ’01, moves on. A couple of chestnuts from the George W. Bush file get the audience going, but just when the people seem to be settling in for a nice, comfortable evening of Republican-bashing, Kreisler turns his fire on disaffected Democrats.

“Remember when everyone had Obamamania?” he asks what, judging from the chatter, is a crowd full of Obamamaniacs. “Once Obama was in office — oh my God.” The greedy look of a true believer comes into his eye as he starts ticking off agenda items on his fingers. “First thing he’s going to do is he’s gonna get us all out of Iraq. Then he’s gonna fix the economy. Then we’re all gonna get our homes back. Then the icebergs will grow back and Princess Diana will riiiiise from the grave!”

Pouting liberals with their messianic hopes, he continues, are “like spoiled 10-year-olds who’ve been begging their parents for a puppy. And they finally got the puppy for Christmas, and they’re like, ‘Oh, he’s so cute! He’s gonna close Guantánamo!’ And 18 months later we’re all ... ” — and here, Kreisler puts on a whiny child’s voice — “Mom, he’s pissing all over financial reform!”

Well, you had to be there. E.B. White once wrote that dissecting a joke is like dissecting a frog: Few people are interested, and the frog dies of it. So, too, with trying to reproduce stand-up on the printed page.

On stage, though, Kreisler is drawing appreciative laughs. He parts company with most other contemporary political comics, from the bitter cynicism of Lewis Black, say, or the smarmy knowingness of Dennis Miller. In his show, he turns serious and sincere.

“I’m a student of history,” he says. “And I love American history — that’s what got me into doing comedy, it’s the idea of the power of words.” One half expects to hear a fife-and-drum corps start playing in the background. “There are three words that make me proud of America. We the people. Those are powerful words, and sometimes it upsets me that the Tea Party stole them, but they’re powerful words and no one owns that idea that we the people have power.”

Then, just before he begins to lose the audience which, after all, came here for laughs rather than a civics lesson, Kreisler pulls them back in: “We used our power when the worldwide economy fell apart, when we the people stood up and said, ‘Hell no, I will not pay for my mortgage!’ ”

Bada-boom.

Kreisler considers himself a satirist, not a straight stand-up comedian. Over the past decade he has written for outlets ranging from Comedy Central to Reader’s Digest, and for three years he produced a regular column for the financial website TheStreet.com. Today, in addition to his various stage performances, he also blogs on his website, www.jeffkreisler.com.

“It’s either a curse or a good thing about my career,” he says, self-deprecatingly and inaccurately, “that I have a lot of projects that are in various stages of failure.”

He works a variety of venues, from New York comedy clubs to college campuses and even a New Jersey racetrack, doing anywhere from one to four shows in a week. He recently opened for comedian Dick Gregory, and was invited to perform at The Economist’s “The World in 2011” conference. His wife, Anne Teutschel, a performer, casting director, and theater and speech professor at the City University of New York, often helps out on his shows. At his Washington performance, she handled the lights.

A trained lawyer who still maintains his California bar license — for the same reason Tammy Wynette kept her beautician’s license for years after she hit it big: You never know when you might need it to fall back on — Kreisler is able to cobble together enough writing and performing gigs to support himself doing what he wants to do. It is “a self-starter business,” and he constantly must decide whether it’s worthwhile to put time and effort into a new idea that might not pay off. On the other hand, “if you worry too much about something ending up in a paycheck, you’re not going to go with it. So I try to find the time to let myself not worry about what I’m doing and just let it happen.”

Ideas come from many sources. A foot-and-a-half-tall stack of newspapers, many marked up and underlined, and a basketful of old notebooks clutter the Hoboken, N.J., house Kreisler and Teutschel share. He takes walks around the neighborhood to help him think, mourning that the widespread use of hands-free phones means that he is no longer the only person pacing the streets who appears to be talking to himself. He tries to force himself to keep something approximating business hours. Sometimes, though, he just sits and watches the day go by.

Perhaps Kreisler’s greatest success has come from his 2009 book, Get Rich Cheating (HarperCollins), which he has developed into a stage show performed at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, the Duke University business school, a few law schools, and several corporate retreats, among other places. A faux wealth-building seminar, Get Rich Cheating takes a satirical look at our obsession with money and willingness to take shortcuts to obtain it. Kreisler describes its tone and style as “Tony Robbins meets Jim Cramer meets Stephen Colbert,” skewering everything and everyone from millionaires who buy their way into the U.S. Senate to Wall Street traders who escape their ruined firms with golden parachutes to CEOs who preach the free-market doctrine while holding their hands out for government bailouts. Among the positive reviews, Penthouse magazine called the book “Catcher in the Rye for evildoers.”

Stand-up routines today are like what Broadway shows used to be: You start on the road and hone the old stuff while trying out new material, experimenting with different combinations and emphases until you find what works and can bring that back to bigger houses and boffo reviews. The night before the Washington show, Kreisler tried untested jokes before about two dozen people at a small club in the West Village. It was a slow Thursday, and by his own admission some of his routine, like the Mormon jokes (“Mormons say they support the sanctity of marriage. Do they think that sanctity means eight?”) flopped. He dropped them. Other bits, however, including the mortgage joke, got a laugh; Kreisler kept them in the show.

Why do political humor when most of the big-time comics seem to get HBO specials doing sex and relationship jokes? “It was just always what I liked to talk about and think about,” Kreisler says. He is careful to keep satire from crossing over into screed. “If there’s something to be made fun of, I make fun of it.” The great divide in American life, he thinks, is not so much between Democrats and Republicans as between haves and have-nots. “You see the influence of money in politics, so I’ve taken those things — money and fairness and the abuse of power — as my framework,” Kreisler insists. “I’ve always been a stand-up-for-the-little-people guy. But I’m very open to anything that’s ridiculous.”

Political humor has a long and honorable history, from Aristophanes to Will Rogers to Bill Maher. But its practitioners face particular challenges. Rip your material from today’s headlines, and you risk it becoming as stale as yesterday’s newspaper. A few iconic figures, like Ted Kennedy and Sarah Palin, may endure as targets, but most others, such as Christine O’Donnell, the Tea Party’s failed Senate candidate in Delaware, already are specks in the national rearview mirror.

If it is to be sharp, Kreisler says, political humor also requires a level of political literacy that an audience might not have. Depending upon where you stand, for example, the views of newly elected Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul on the Federal Reserve might be ripe for mockery, but the room will fall deathly silent if the crowd doesn’t know who Rand Paul is or what the Fed does. That is another reason Kreisler tries to build his humor around larger ideas, peppering them as needed with the politician or scandal of the moment.

And though it may seem obvious, political humor has to be funny — or it’s just another attack ad. “In most comedy clubs,” Kreisler says with a veteran’s jaded eye, “your job is to distract [the patrons] while they buy drinks. So it has to be the joke above all else. I try to always remember that I am an entertainer.”

Kreisler confesses almost sheepishly that he turned to humor neither as a tortured soul nor as an oddball trying to fit in. Instead, he came from a high-achieving academic family. His father, Michael Kreisler ’62, was a Princeton physics professor before taking a faculty job at the University of Massachusetts and moving the family to Amherst, Mass., where Kreisler grew up. After prep school at Exeter, Jeff followed his two siblings (David ’88 and Michele ’90) to Princeton, majoring in politics with a certificate in Russian studies, playing lightweight football, and covering sports for WPRB.

With graduation approaching, Kreisler applied to law school “because it seemed like what you do, which is a horrible reason to do it.” He began classes at the University of Virginia law school and the intellectual demands of law school engaged him, even if the prospect of practicing law afterward did not. “I wanted to be Thomas Jefferson or Thurgood Marshall,” he says, but at the time, he envisioned himself instead as a law-firm drone, “alcoholic and divorced” at 35. Midway through his second year, he decided to take time off.

Moving to San Francisco, Kreisler supported himself for several months as a freelance photographer. He returned to Virginia the following fall and earned his degree, then went back to San Francisco and took the California bar exam, using his law degree — negotiating the settlement of software- licensing claims and helping sole practitioners who needed an extra hand — to cover his expenses while getting established as a comic. Two weeks of reviewing documents, he found, paid as much as two months of regular work in comedy.

His legal training was not entirely wasted, Kreisler says, citing similarities between lawyers and comedians — and no, that is not the setup for another joke. Both, he thinks, “have the job of looking at what’s in front of them, breaking it down into its components, and then rephrasing or explaining it for their own ends. As much as it is hard, I love the process of getting a new subject, having no idea what it is about, studying it, breaking it down, and then re-presenting it.”

The fall of 1999, when Kreisler returned to San Francisco, was a propitious time to enter the Bay Area comedy scene. The mid-’90s comedy boom had quieted down, so that “the only people doing it were those who were really good or couldn’t do something else. In a way, that was good because it eliminated those who weren’t serious.” Into which camp did Kreisler fall? He laughs. “I was that stubborn person who tried something and refused to quit until it destroyed him.”

The 2000 presidential election campaign inspired one of Kreisler’s first stage jokes, the prescience of which still makes him cringe. After the first presidential debate, pundits praised George W. Bush for performing better than expected. “I don’t want that to be the standard,” Kreisler riffed. “I don’t want to wake up in two years and find that New York and Washington, D.C., have been attacked, but Bush did ‘better than expected.’” A little more than a year after Sept. 11, Kreisler moved to New York, where Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show recently had become popular, and which seemed an attractive place for Kreisler’s brand of humor.

For almost a year, Kreisler did stand-up when he could. Having two successful older siblings gave him, he felt, some leeway within the family to pursue a less traditional and less lucrative path. “Being the youngest kid and a little bit spoiled, I didn’t feel the urge that I had to make money to support myself,” he says. “There was a sense of ‘I’ll be OK.’” In 2004, he and Dan Piraro, who draws the comic strip “Bizarro,” toured the country with a political comedy show they created called Bizarro’s PolitiComedy-A-Go-Go. They started out in Texas, not the most likely spot for a couple of lefty comics during Bush’s re-election campaign, but their show won a following. “I saw that there was an audience for political comedy,” Kreisler says. “You just had to find it; it wasn’t traditional.”

The Bizarro tour led to offers for nightclub gigs and shows for groups of college Democrats. In 2005, Kreisler was approached to write a regular column for TheStreet.com, offering a satirical look at the business and financial news. A year later, a publisher asked him to write a book, but when Kreisler submitted a first draft of Get Rich Cheating, the publisher discovered that it was not the compendium of Internet columns that had been anticipated, and backed off. Eventually, Kreisler sold it to HarperCollins, which, in a bit of good timing, published it in 2009 in the wake of the financial collapse and the Bernie Madoff scandal. Suddenly, Kreisler’s tongue-in-cheek paean to getting ahead by breaking the rules made him seem like an oracle.

A generation ago, the goal of most comedians was an invitation to sit on Johnny Carson’s couch. These days, the options for exposure and success are much more varied. There is still Jay Leno’s couch — and the chairs of David Letterman, Conan O’Brien, Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Kimmel, Graham Norton, and numerous others on late-night network and cable TV. Comedy sites flourish on the Internet. But as there are more ways to get noticed, there are also more people trying to get noticed.

Despite his growing success, Kreisler says he is sometimes hampered because his diversity of interests and talents keeps him from fitting easily into a niche. Club bookers also tell him, “Yes, you’re very funny, you have wonderful credits. I don’t need another white, Jewish guy.” The idea of organizing his own comedy tour, as many comedians do, no longer appeals. “I like being at home.”

Asked to name a comedian whose career he’d like to emulate, Kreisler offers up Steve Martin, who also started out doing stand-up in San Francisco but has branched out to become an actor, playwright, musician, New Yorker contributor, and best-selling author. “I want to be at a point where I can work on different things,” Kreisler says, “where I can write for a TV show, develop a TV show, and write a play, without having to go through each one’s 10-year

dues-paying process.”

Over the years, he has experienced nights on stage when he could do no wrong, as well as nights when — as he admits — he bombed. He talks about both willingly. “When you’re doing badly,” he says, growing philosophical again, “it’s painful, but those nights are educational. You can try to figure out what’s going wrong and how to fix it. And if you can sur vive the horrible nights, the good ones are that much better.”

As for the good nights, he continues, “I imagine it’s what surfing is like. If you felt like doing a handstand or surfing on one foot all of a sudden, you could do it. I can see why some comics have gotten addicted to drugs — you’ll do anything to get that high again.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

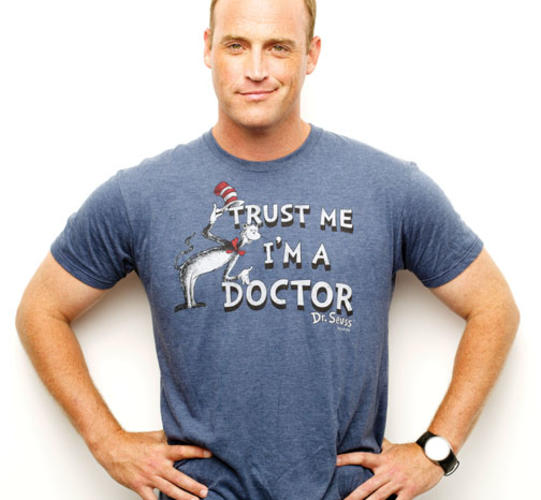

Stand-up Spotlight: Matt Iseman ’93

Résumé Stand-up comedian and television personality; hosted “Sports Soup” (Versus) and “Ninja Warrior” (G4) and two other game shows; regular cast member on “Clean House” (Style Network); graduated from Columbia medical school; pitched on Princeton’s 1991 Ivy championship baseball team. Majored in history.

Giving up medicine

Iseman was in the middle of his residency when he decided to take time off to examine his commitment to becoming a doctor. He had done stand-up before and was attracted to the possibility of doing something creative. His parents (his father, Michael ’61, is a pulmonologist) were supportive, telling him to do what he loved — although, he jokes, “I’m sure they wish I would have come to that realization before medical school.”

Personal challenges

Iseman has had several health problems of his own, facing medicine “from the other side of the stethoscope,” as he puts it. In 2007, a cancerous tumor was removed surgically, and Iseman has been cancer-free ever since. Humor has been the most effective way of dealing with the stress of his illnesses, he says. So, is it true, then, that laughter is the best medicine? “Well,” he quips, “Vicodin works a lot better.”

Cleaning house

The experience of working in some very messy homes doing Clean House has affected Iseman, who says it has made him more careful to keep his own home clean. “When you come home, you start throwing things out, saying, my God, I don’t want to end up like those people.” Perhaps the most impressive home he has seen was the former palace of Saddam Hussein, where Iseman entertained the troops during a USO tour in Iraq several years ago. “It was unbelievably ornate,” he says, “even fancier than Ivy.”

Always a groomsman, never a groom

Although he is tall, handsome, and a successful TV personality, a part of Iseman’s stand-up routine concerns the fact that he is the only one among his high school and college friends who never has married. “In your 20s, [being single] is fun because there are lots of single girls at the weddings,” he says, “but now everyone’s just lecturing you, going, ‘What’s your problem, dude, hurry up and get married!’” Isn’t it true that women are attracted to comics? Iseman answers: “I think they’re more attracted to doctors.”

Stand-up Spotlight: Mary Cait Walthall ’08

Résumé Performs with several improvisational comedy groups in Chicago, including the iO Chicago Theater, Baby Wants Candy, and A Dozen Red Roses; takes classes in musical improvisation and comedic writing at The Second City Chicago’s training center; wrote and performed in the Triangle show and for Quipfire!. Psychology major.

Princeton training

Walthall always knew she wanted to pursue a career on stage. As a freshman, she auditioned for several plays without success before her father suggested that she try Quipfire!, a campus improv troupe, whose members act out short routines in which ground rules are set ahead of time. Today, Walthall does only long-form improvisation, in which performers develop longer routines focused around themes or characters. Walthall says that her experiences with Quipfire! and the Triangle Club gave her the courage to pursue improv as a career.

Musical improv

Walthall specializes in musical improv: An audience member shouts out the title for a show — “Department of Redundancies Department” or “Adventures of a Pretentious Illiterate” are two Walthall has done — and performers, along with an accompanying band, improvise an hour-long musical show on the spot. Cooperation among actors, and between actors and musicians, is essential.

Making ends meet

Walthall’s schedule can be grueling. In a typical week, she might have two performances and a rehearsal for another show, plus classes. She is still a struggling artist with a day job assisting researchers at the Northwestern University medical school. Her goal is to pursue comedy as a paying career. Opportunities abound in Chicago, and she has appeared with performers, such as Saturday Night Live’s Vanessa Bayer, who have gone on to bigger things. Walthall also is taking classes in comedic writing because “the way to do what you want to do in comedy is to write.”

Zen comedy

“For me there’s nothing like going on stage with nothing,” Walthall says. “It’s an incredible high when you manage to come up with something that makes people laugh. It’s completely Zen Buddhist. You can’t think beyond the present moment.”

Stand-up Spotlight: Justin Purnell ’00

Résumé Created and hosts the weekly School Night show of the Upright Citizens Brigade (UCB), a New York comedy group co-founded by “Saturday Night Live” alum Amy Poehler; co-produces a UCB improvisational show; formerly high-yield credit analyst for seven years with Goldman Sachs; published “The Nassau Weekly” and appeared on WPRB. Economics major.

The funniest man on Wall Street

Purnell was accepted into the Goldman Sachs training program, but after two years on Wall Street he began taking Saturday-morning comedy classes at the UCB Theater. For several years he worked at Goldman from 7 a.m. until 8 p.m. and then performed, wrote, or helped to promote the UCB Theater until after midnight — a schedule that was “not conducive to good sleep habits.” In 2007, he left Goldman to work at the UCB Theater full time.

Different worlds

Purnell says he enjoyed his years at Goldman Sachs, particularly working with “very Type-A, very reliable people who show up on time.” The UCB Theater office, he notes, does not even open until 11 a.m. “It’s a different mind-set in comedy,” he muses. “You don’t walk in at 7 a.m. and say ‘I’m going to write comedy until 12 p.m.’ and just do it. It’s about what’s funny now. That tweet might turn into a sketch or a TV show.” After leaving Goldman, Purnell was bombarded with e-mails from colleagues who envied his decision to try another career path.

Improvisation

Producing the UCB Theater’s weekly improv show has enabled Purnell to meet and work with famous comedians. He calls Tina Fey a friend, and describes hanging out after one show with Saturday Night Live alumni Rachel Dratch and Will Forte, 30 Rock’s Jack McBrayer, and Mad Men’s Jon Hamm, who engaged Purnell in an impromptu comedy sketch about their checked shirts. “I thought, ‘What is this life?’” Purnell marvels.

Moving up

Purnell sees his future in entertainment, but not on stage. Though he says it’s “always fun to get a big laugh from an audience,” he hopes to make a comedy career behind the scenes, developing the next 30 Rock or Parks and Recreation.

Stand-up Spotlight: Josh Kornbluth ’80

Résumé Oakland, Calif.-based humorist specializing in autobiographical monologues; wrote and starred in two films, “Red Diaper Baby” and “Haiku Tunnel,” with another, “Love & Taxes,” in production; hosted “The Josh Kornbluth Show” on the San Francisco public-television station. Majored in politics.

Growing up red

Much of Kornbluth’s work deals with his Communist parents. Going to Princeton was fine with them, he says, because they knew that the bourgeoisie always got the best education, and he could use what he learned there to bring about The Revolution. Family friction arose after graduation, however, when he went to work for two newspapers run by — gasp — Socialists.

Better late than never

Kornbluth never finished his senior thesis. On the day of the 2004 election, frustrated by what he saw as America’s fraying democracy, he decided to ask his adviser, Professor Sheldon Wolin, about completing it. Wolin persuaded him to write his thesis as a dramatic monologue. (See “Thesis Envy,” in the Dec.12, 2007, PAW.) The result, Citizen Josh, has been a stage hit that Kornbluth took on tour to India last summer and that got a “decent” grade from Wolin. Alas, Kornbluth still must submit it officially to the politics department, something he says he intends to get around to very soon.

Love and taxes

Kornbluth’s most recent project was a paean to paying your taxes. The lead character, played by Kornbluth, has prided himself on not “supporting The Man and The Man’s wars” by paying taxes. When he falls in love with a public-school teacher, he realizes that most of the things he values in society — public education, libraries, hospitals — are supported by tax dollars. “A pro-tax love story,” Kornbluth insists. “I don’t see how it can fail commercially.”

The generation gap

In San Francisco, Kornbluth wanted to make literary or political references, but unfortunately, there were not a lot of Trotsky jokes that went over well in comedy clubs. Still, he says, don’t count them out: “Anything that involves ice picks has got to appeal to a generation that likes the Halloween slasher movies.” He often appears on college campuses. Is it hard for a 50-something comic to connect with a college-age audience? To the contrary, Kornbluth says, the generations have similar concerns: “I think our goals and desires are shared,” he says.

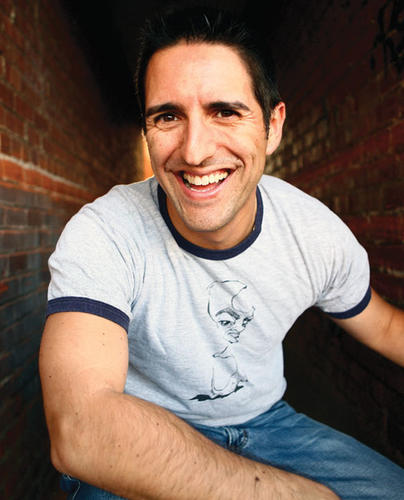

Stand-up Spotlight: Joe Hernandez-Kolski ’96

Résumé Actor, writer, and performer; host and co-writer of the Not So Foreign Filmmakers Showcase; toured in a hip-hop adaptation of Shakespeare’s “The Comedy of Errors”; performed on two seasons of HBO’s “Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry”; has appeared in several films. Majored in history with certificates in African-American studies and theater and dance.

Growing up on stage

Hernandez-Kolski began doing professional theater at the age of 12 with the Arts Ensemble of Chicago. When he arrived at Princeton, however, he resolved to “avoid theater at all costs,” but his resolve quickly melted. He became a regular performer in shows at Theatre Intime and at 185 Nassau St. and continued writing poetry, which he had begun in high school. “You can’t not be what you are,” he says.

Challenging the audience

After graduation, Hernandez-Kolski moved to Los Angeles, where he did ensemble theater and his own poetry-based comedy shows. He says he tries to challenge his audience. One show consisted of Hernandez-Kolski announcing the title of his act, “No Disclaimers,” and then proceeding to deliver a riff of nothing but disclaimers. At first, he recalls, the audience “was ready to set the place on fire,” but when they caught on, the house erupted with applause. He later performed it on HBO.

No pigeonholing

Hernandez-Kolski continues to work on stage, in film, and on TV. He aims to challenge people while making them laugh, he says. He had small parts in the movies Hancock and The Soloist, and recently finished a film with Armand Assante. He wrote and acted in Afterschool’d, which was a finalist for NBC Universal’s Comedy Short Cuts Film Festival. In addition to stand-up and poetry gigs, he stars in a two-person show with beatboxer Joshua Silverstein and performed in The Bomb-itty of Errors, a hip-hop adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors, in London’s West End. He also teaches hip-hop culture and spoken-word poetry around Los Angeles. “I think I’ll always be balanced between creating my own material and doing other people’s material,” he says. “I love performing.”

No responses yet