‘I’m Painting the Experience of a Moment’

After gathering force for years, Mary Weatherford ’84 is now an art star

MARY WEATHERFORD ’84 NEVER FAILS TO surprise, I think, as I watch her on stage.

She is joined by artist Suzanne Jackson, collector Komal Shah, and a couple of curators for an event in May celebrating female artists at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Weatherford’s answers to questions are eclectic, ranging from the scientific (“Neon and argon are on the periodic table, and if you apply electricity, they glow red and blue”), to the political (“The point is agency — to see ourselves as subjects, not as objects”), to the poetic (Trying to make a great painting is like “grabbing for smoke”).

Her presence, too, surprises. Her long-sleeved emerald dress clings to her frame, its draped-knot collar adding sass to the class. Her auburn hair falls to her shoulders. All elegance, until the clunky tomboy shoes: a pair of caramel-colored Oxfords. No heels for her.

And her career surprises. It started inadvertently at Princeton, kept going quietly for five years in New York, and drew art-scene attention with her first show. Slowly, Weatherford gathered force, especially after she moved back to California 10 years later.

Today, at 61, she is an art star, represented by major galleries (David Kordansky and Gagosian), fresh off an exhibit in Berlin (Drink the Wild Air) and one in New York City (Sea and Space). Her very smallest paintings sell for $100,000 and the largest for many times that, huge canvases with veils of transparent hues and attached bars of neon, cords dangling provocatively.

Critics and curators say she shows “an ecumenical historical awareness” and is “revivifying abstract art.” Her biographer Suzanne Hudson *06 writes: “Each painting exists, fully realized, as though a toothpick planted in shifting sand — hardly a defense against a swell or a riptide, but a statement implying a question about encompassing fate.”

Weatherford possesses a prodigious intellect as well as an eye-hand harmony that would make the average carpenter jealous. Her subjects include politics, mathematics, outer space, philosophy, linguistics, literature, opera, art history, bridges, engineering, science, faith, death, and resurrection. And the themes of Emily Dickinson.

Her paintings are lush, enormous, full of sentiment, and devoid of sentimentality — at once epic and deeply personal. The stakes are as big as the canvases, the paradoxes as profound as the painter herself.

IN AN INTERVIEW A FEW DAYS BEFORE the SFMOMA event, Weatherford recalls her very first memory: “Pink and white stripes,” she says, the image popping out. “My mother is lowering me into my crib. I think they were sheets, but maybe they were curtains.”

The setting for the memory is Ojai, California, where Weatherford was born in 1963. Her father, William, was the vicar of an Episcopal mission; her mother, Regina, a history graduate of Stanford.

“Ojai is considered a holy place,” Weatherford says. It attracted “interesting people” like the Indian philosopher Krishnamurti and Franklin Fireshaker, a Ponca elder who was responsible for the first paintings that Weatherford ever saw — dreamscapes of tribal legends.

“It might be the only place in the United States where the mountains run east-west,” Weatherford says of Ojai’s particular magic. “The moon never sets. You’re always seeing it in the sky.”

Mary, the first child, was followed by sister Margaret and three brothers. Her mother educated the five in her own way, outlawing coloring books in favor of their own creations. She and Mary shared a fanaticism for handcrafts — complicated macramé, Ukrainian eggs, and later, clothes sewn from Vogue patterns. During the craze for click-clacks, they poured resin into decorative grape molds, studded the resin with flowers, dropped in strings, and let the balls set. “We’d start click-clacking, and they would shatter,” Weatherford says, laughing. The flowers had made them unstable.

When she was 6, Weatherford’s parents took her to see a Vincent van Gogh show. William Weatherford held her up in front of Wheatfield with Crows, one of the artist’s final paintings, and told her it was the most frightening painting he’d ever seen. “He held me there for a long time so that I could see why,” she adds.

William also spent hours teaching his daughter about cars and carpentry. “I hated helping him bleed the brakes,” she says. When Mary decided to build a wooden box, William, whose own father had been a carpenter, insisted she make a “proper” one — without any screws and with inset handles.

“I learned car mechanics and joinery,” she says wryly. “That’s why I was comfortable in the sculpture studio with power tools.”

In high school, in San Diego, Weatherford excelled at chemistry and calculus, which she credits for her “love of the parabola.” Art she considered tame. “We’d make watercolors of an old dock or an old cowboy boot,” she says, dismissively. She was “smitten” with theater; with friends she saw Shakespeare in Balboa Park, and they turned plays into dramatic monologues for the speech team.

ONE THING THAT ATTRACTED WEATHERFORD TO PRINCETON was its proximity to Manhattan and Broadway. In her first few days on the East Coast, she stayed in New York with her aunt, an art educator, and her uncle, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They took Weatherford to the Met and to the blockbuster Picasso retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art.

“I loved New York City. I loved the people, the accent. I was an immediate East Coastophile. I thought, ‘Thank God I’m out of San Diego.’”

Weatherford auditioned for a short play her first week at Princeton and later performed with eXpressions Dance Company and Theatre Intime. But then she took an acting class. “I couldn’t deal with it. When we had to start saying things to each other like, ‘Boo! Bah!,’ copying each other and stuff, I didn’t want to do it. So I dropped out.”

Figuring she should do something serious rather than major in theater, at first she settled on architecture. Meanwhile, her roommate was from Montclair, New Jersey, and a neighbor would take the two to SoHo. “We went to the Solomon Gallery and Leo Castelli,” Weatherford remembers. “We saw Walter De Maria’s Earth Room on Wooster Street. Can you imagine a 17-year-old seeing the Earth Room?”

But it was during her sophomore year, in Jerry Buchanan’s painting class, that Weatherford fell in love with painting. She became one of eight classmates to major in the “tiny” visual arts department, housed then, as now, in a former elementary school at 185 Nassau St. with an air of easy informality. “Princeton was a kind of sleeper art school, unlike Yale, Rutgers, or Tyler [at Temple],” Weatherford says. “If I had been at a very competitive art school, I might not be an artist today.”

It wasn’t just the lack of pressure at 185 Nassau that shaped her. “Taking physics was a real thrill. And comp lit. And Greek and Roman sculpture. I took silent cinema and the coming of sound from P. Adams Sitney, the preeminent scholar of American avant-garde film.” She even took an engineering course.

She appreciated the intellectual rigor within the visual arts department — to a point. “We couldn’t major in studio art without fulfilling the requirements for art history. I took Rococo to Revolution, where I learned to look at things with a socioeconomic lens. Then I got a C-plus in Renaissance Architecture, a 200-level course, even though I studied hard; I made hand-drawn flash cards. I said, ‘OK, from now on I will only take 400-level courses. I will only write papers.’ I did a workaround.”

Sitney called her a “walking paintbrush.” Sculptor Andrea Blum asked her point-blank if she intended to be an artist. Shocking herself, Weatherford blurted, “Yes!”

“For me to make art about my experience, for me to think that is a worthwhile topic — that’s political. ”

One faculty member who was influential was Sam Hunter, a professor of art and archaeology, historian of modern art, editor, critic, and a curator at the Princeton University Art Museum. She became his research assistant and later he championed her, buying paintings from her friends, including her in a show, and writing the first scholarship on her art.

When Weatherford graduated, she snagged a coveted slot in the Independent Study Program at the Whitney Museum of American Art. “I borrowed someone’s Datsun and drove with a friend to an apartment at 100 Forsyth St. I was subletting from Marjorie Keller, the girlfriend of P. Adams Sitney. It was this avant-garde scene — all these women. At a party, we climbed to a fire escape and ate steak tartare. I thought, ‘This is the life.’”

WEATHERFORD HAD ARRIVED IN NEW YORK when abstract painting and the conversations around it had been in full force for four decades. Jackson Pollock was the giant of abstraction. However, feminist artists like Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro had begun to challenge the male hegemony.

Weatherford’s personal list of “art heroes” both defied and reflected the times, including Old Masters and American modernists active between the two world wars. But painters whose style is seen easily in her work include Morris Louis (“I love the veils”), Helen Frankenthaler (“My stain paintings with silk-screened flowers were inspired by her lithographs in the Princeton collection”), and Joan Mitchell (“the master of color”).

Private, even secretive, about her art, Weatherford worked at a postcard-and-photo-book shop in SoHo favored by downtown artists, then at various galleries. She earned attention in a cheeky 1988 New York Press roundup that called her the most “congenial, helpful, and non-threatening director around.”

She was painting “targets,” concentric circles that she used, partly, as a vehicle for color study. (Imagine her doing with circles what Josef Albers had done with squares.) She remembered visiting natural history museums as a child and seeing a slab of a tree with the dates marked off on its rings. She saw them as circular timelines, a visual representation of the idea that time and the way we evolve is not linear. A scene from Vertigo inspired her — Kim Novak’s character gazes at a giant redwood and says, “Here I was born and here I died.”

In 1989, Weatherford had a project room at New York’s PS1, an arts center later affiliated with MoMA that showcases art overlooked by established museums and galleries. Her targets invited comparisons to pop artist Jasper Johns and color-field pioneer Kenneth Noland, but she had digested a heavy dose of feminist film theory at Princeton and postmodernism at the Whitney and was developing a renegade purpose: “I was using formats invented by men, but I wanted to subvert them.”

Soon she scaled the targets up, way up. “I decided that the next logical move for a feminist artist was to walk straight into the house through the front door — to make big paintings,” she said in a 2009 talk.

Her provocative titles alluded to tragic female characters from opera, novels, and ballets: Cio-Cio-San, Camille, Odette. She photographed herself in a flowing dress, weeping, and transferred it onto canvas. She painted an array of red trees titled Her Insomnia. Hysteria, female sorrow, the social assumptions that lead to the undoing of women — the feminist themes were fairly explicit.

Also explicit was her fascination with the surface of the painting. Some of her Violetta paintings feature a target created with a handmade “drawing machine” using string, a metal square edge, and a pencil to carve ovals into wet oil paint. (“It was like a giant Spyrograph.”) Another features delicate, silk-screened violets that flutter across an expanse of almost fluorescent yellow.

She was also experimenting with materials that lacked the “historical baggage” of oil and the “sheen” of acrylic. She loved the vinyl-based paint Flashe. “It was so matte, it absorbed the light. Like a fresco.”

From targets she moved to silk-screened images: unearthly white peonies against a black-green ground, blood-red rose stems with thorns, oil-and-ink feathers, black swans and white swans.

A New York Times art critic praised Weatherford’s “determination to turn abstract painting into a crossover art form.” Sam Hunter wrote in New Directions that his former student’s “ease and mastery in large scale form recently combine with vibrant color interaction and nuanced surface to subvert even her most didactic intentions. … Her art clearly sustains her declared aim to ‘make political art that can be beautiful.’”

The year 1992 was a watershed. After a big show, she felt her work was too cool, too distant. She became less concerned with art history and more with her own history. There was a moment, she says, when she decided, without trepidation, to oppose postmodern ideas, to become “the author rather than the reader.”

“For me to make art about my experience, for me to think that is a worthwhile topic — that’s political,” she says.

There was another shift: She turned to assemblage and things she’d done in her childhood. “When I was in elementary school, we would make these incredible tidepools. We’d line the bottom of a shallow flower pot with sand, and build a tidepool with stones and fill it with shells, and I’d made sea anemones by pushing clay through garlic presses. I’d pour the resin over the whole thing.” She would set it on her dresser and peer into this ocean world.

In 1994, Weatherford made her first painting with starfish,

the ocean is in the sky. Moths, chrysanthemums, jellyfish, shells, and sharks all became her subjects, whether painted on the surface or affixed to it. She added whole sea sponges, what one critic called “organless masses … extending in bulbous efflorescence.”

WEATHERFORD MOVED HOME TO CALIFORNIA IN 1999. She doubled down on landscape painting with coastal scenes, cloudscapes, birds, rocks, and sea caves, describing her themes as “the big ones: mortality and morality.”

As she moved to staining, the surfaces of her works changed. She seemed to stretch out — more white space, more loose and layered washes, more veils of luminous color. The caves yawned, inviting the viewer into a mysterious, immersive environment. Weatherford describes the style today, with a laugh, as “Frankenthaler meets Warhol.”

Then came Bakersfield.

Wanting to make an exhibit of large-scale paintings in a museum-sized space, she accepted a residency at Cal State Bakersfield that would have her teach a five-week class and make paintings responding to the high-desert landscape.

“Everything is transient, it’s a moment that will be then gone. That’s loss; joy and loss. They are somehow knitted together in a depiction of a moment of joy and utter hopelessness.”

At the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley, in the vast and prosaic Central Valley, Bakersfield is known for pistachios, almonds, and oil fields. “It’s like Texas inside California, or the town that time forgot,” Weatherford says. “I wanted to see the cotton fields, where Texans and Oklahomans came after the Dust Bowl. I wanted to research the Kern River, the place where John Steinbeck conceived The Grapes of Wrath, the Bakersfield sound.

“I got into Merle Haggard and Buck Owens and looked around for honky-tonks where these guys still played. And they did, at Trout’s in Oildale. I would go to the club and try to do the two-step.”

The town’s main drag was once studded with fancy hotels and businesses, but years after Highway 99 diverted traffic, only derelict shells and old neon signs remain. One of them is a giant T — all that is left of a Thriftimart sign. The Bakersfield signs haven’t been taken down just because, well, there’s no reason to.

“The color of the sky in the San Joaquin Valley is so beautiful,” Weatherford says, “and at the end of the afternoon, the sun goes down behind the mountains, but it stays light for a couple of hours. One day I was driving around and the sun was setting and the sky was turning colors and these signs were coming on.

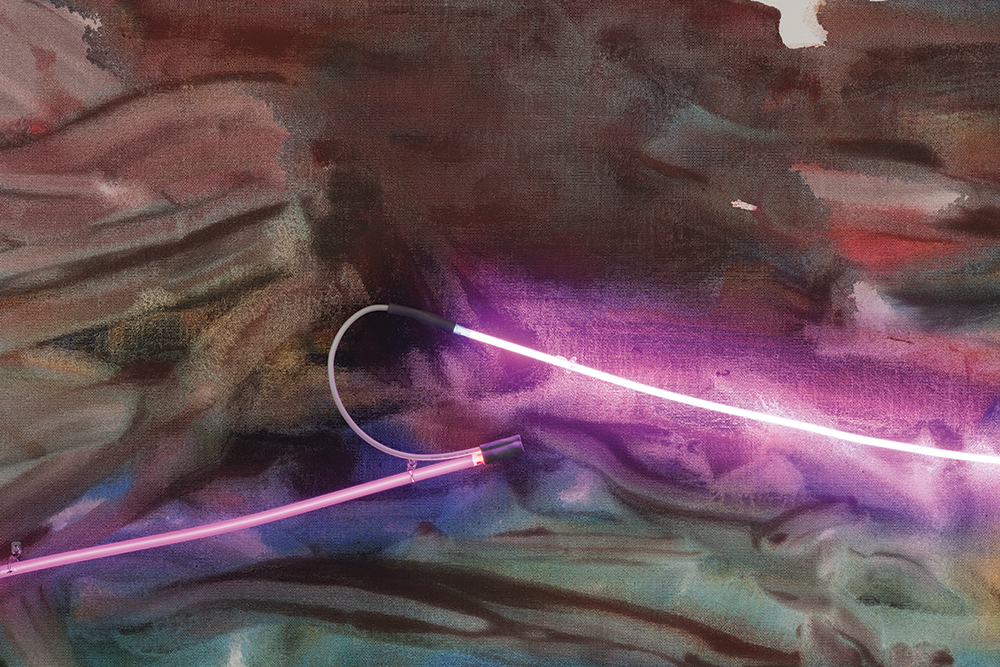

“I thought, I wonder if I could put a piece of neon in a painting. The neon will represent the town. Other artists have put neon words on canvases, but I wanted the neon to be not a sign, not a letter, not something recognizable, but an effect. This goes to the loss, the seeing something in your peripheral vision that’s passing you by. You see it, it’s passed. You don’t quite recognize it, but you know it went by.”

She called Center Neon, a 50-year-old family business in Bakersfield, and asked how much they’d charge for a 3-foot-long crooked piece of neon. She mounted those eerie lights on color-washed surfaces, setting the canvas aglow, and left the power cords hanging heavy and crude, plugged into anchoring transformers.

“I had come to a point where I thought, I want to make work about people’s lives. Whenever you see photographs from space you see the cities glowing. Or, even when you’re driving through a dark landscape, you see a light, and you say, ‘There’s somebody, some human, there.’”

The neon tubes are literal lights as well as linear elements; a cut as well as a compositional force. They illuminate the layered surfaces and jolt them alive. Critics have compared the canvases to visual tone poems, “psychogeography,” and a “reframing” of the abstract painting and of the tradition of art.

“I don’t ever think of [my] work as landscape in the sense of ‘I’m painting that landscape over there,’” Weatherford told an audience in Berlin in June. “No, I’m painting the experience of a moment that is over. Every experience is one of constant movement, even a conversation. … We enter a dialogue, it’s moving, and we become different people because of it. We lose the person we were when we began.

“This leads to a kind of melancholic state. It may be hard to understand how I might depict that in a painting, but that’s what I’m trying to do.”

TODAY WEATHERFORD LIVE NORTHEAST OF LOS ANGELES, atop Mount Washington, in a midcentury modernist home designed by premier architects, which she restored. She works nearby in Glendale.

After weeks of finagling and many emails, I finally gain entrance to Weatherford’s studio, which resembles nothing so much as an airplane hangar — a clean and exceedingly organized airplane hangar. It is 10,000 square feet with a 10,000-square-foot parking lot and a redwood vaulted ceiling, built after World War II. (It was actually a bolt-manufacturing plant, owned previously by her uncle.)

I wander among the nine staff members and studio assistants who help her keep the space organized for utility. Neon rods are stacked on wooden shelving and packed in boxes; plastic buckets of Flashe pigments are arrayed on horseshoe-shaped tables, beckoning like pots of fingerpaint, and dozens of grouting sponges line up at the ready, clean but colorfully stained.

Weatherford arrives, wearing jeans, a blue sweater with a thick cowl, and work boots. Her hair hangs straight and unstyled. She is accessible and open, making me feel welcome and showing great consideration with her bevy of assistants.

The first question was hers: What did I think of a new canvas hanging behind us, not yet neoned? Was it any good?

She takes me back to the rear portion of her studio. Here she paints alone, with canvases stretched on the floor, a tall ladder nearby so that she can take them in from on high. She points down at the painting in progress. “I’m trying to get a color I saw in the water on Kauai.”

In her now highly evolved method, she spreads over the floor heavy-gauge Belgian linen with an exaggerated warp and weft that creates pockets for the paint. After it is prepped, she mixes Flashe pigments and, using sponges and large brushes, lays swaths of color. The dried canvas is stretched and hung on the other side of the building. She attaches neon tubes (replete with cords), choosing the color for the way they interact with the paint.

She told The Brooklyn Rail art journal that in the studio she hangs the lights with fishing lines and moves them around like puppets. But staff and visitors to the studio jokingly call her “the human level” for her seemingly supernatural eye.

By the time I leave, Weatherford and I are chatting like girlfriends and she’s wondering whether she might come to a writers retreat I lead on Oahu in Hawaii. “I want to write poems about color,” she says.

She did come to the retreat. She didn’t write about color, but rather, in charming iambic verse, about barnacles. She made a lei out of nuts and shells that showed off her manual dexterity. She garnered attention with the flowered pants she donned for dinner, and I’d call her glamorous if that didn’t mask her down-to-earth quality, or her kindness in getting a plate of food each night for my 89-year-old mother.

JUST BEFORE JULY 4, at the Altadena Town & Country Club, I meet Weatherford for a final in-person interview after months of snatched conversations and Zoom meetings. Her initial reluctance to be interviewed has evaporated, and we’ve developed an easy rapport. When I arrive, she’s at her tennis lesson, and when she finishes, she leads me into the dining room for a late lunch.

We talk about Sam Hunter, the tide pools she made as a kid, how her art is political, and why Princeton was the right place for her to study art. She muses about radical shifts in the art world (“Young women are selling work for $1 million”).

We talk about Berlin (“oppressive architecture”), where she has just been for an opening. A few days later, she sends me a transcript of remarks she made there. “There is loss in my works from the very beginning. It’s been made sharper since the death of my sister (in 2012). Yet even before that particular loss, the suffering, the sense of something heavy in the human condition, was already present.

“Take Night Blooms Green — the blooms are transient, they’re moving. Everything is transient, it’s a moment that will be then gone. That’s loss; joy and loss. They are somehow knitted together in a depiction of a moment of joy and utter hopelessness.”

As the waiter clears our plates, Weatherford muses softly: “When an artist observes, senses, takes it in, and then runs all that through the mill and renders it in a way that is meaningful — it’s transcendent, it’s divine.”

Constance Hale ’79 is a journalist and poet based in California.

1 Response

Gary R. Walters ’64 *75

1 Year Ago‘Decorum’ in the Arts

The Academie Francaise made rules defining high art in the 17th century. In addition to creating a hierarchy of types of subject matter (history painting over genre painting) and styles appropriate, they created a kind of grammar called decorum. With this word a moral responsibility is introduced as well.

In a play by Racine for, example, the events needed to take place within the time frame of the story. Similarly with history painting, then considered to be the apogee of painterly effort. In other words, a set of guidelines within which to make and to judge a work of art relating it to its purpose and place.

Media are freely mixed now as they are in this work. Using colored neon tubes attached to abstract very sensitive and very large paintings is to mix different media and their characters.

Such mixing began within the throes of Modernism. Unless we consider frames and settings as part of the work.

However, the neon suggests a realm quite opposite to that of the paintings. Light emitting mechanical structures which we quickly associate with gas stations or movie theaters or Dan Flavin who first used neon as a medium. These neon tubes produce colored light that is reflected from those of the painting underneath. Floating paint elides into other paint, flesh like, cloud like, sky like, expressive of a sensitivity at antipodes from, say, marquees of neon.

This harsh juxtaposition is entirely intended I suppose. To what avail?

The viewer is placed at a crossroads. Is the primary association painterly or conceptual? We can decide to go one way or the other. But not both, for the one excludes the other.

This sensitive painter might think to leave well enough alone without adding the discordant glow (to me) of a neon lit conceptual playground, a visual tilt-a-whirl. Because neon tubes have nothing to do with painterly painting and vice versa, a uniting concept must be introduced. No such concept exists. We could give up. But we have had to think more than see in any case.

Of course this is the 21st century. It is worthwhile considering whether the ideas of decorum still have any validity in the era of anything goes. And where would we find it. Is the experience of the viewer simply an experience of the new as Robert Hughes might have said.

But the new what or the new where? Just the new new is unsustainable. Perhaps in 2024 in America, Planet Earth, that is the point. And then one cannot paint a moment, sorry to say.

But what an extraordinary career on going. How grateful we must be for Mary’s determination and for its generous display in PAW, all too rare, of a graduate’s experience in the visual arts.