Immortality in Plaster

Few know about it, but Firestone Library may boast the world's largest collection of life and death masks

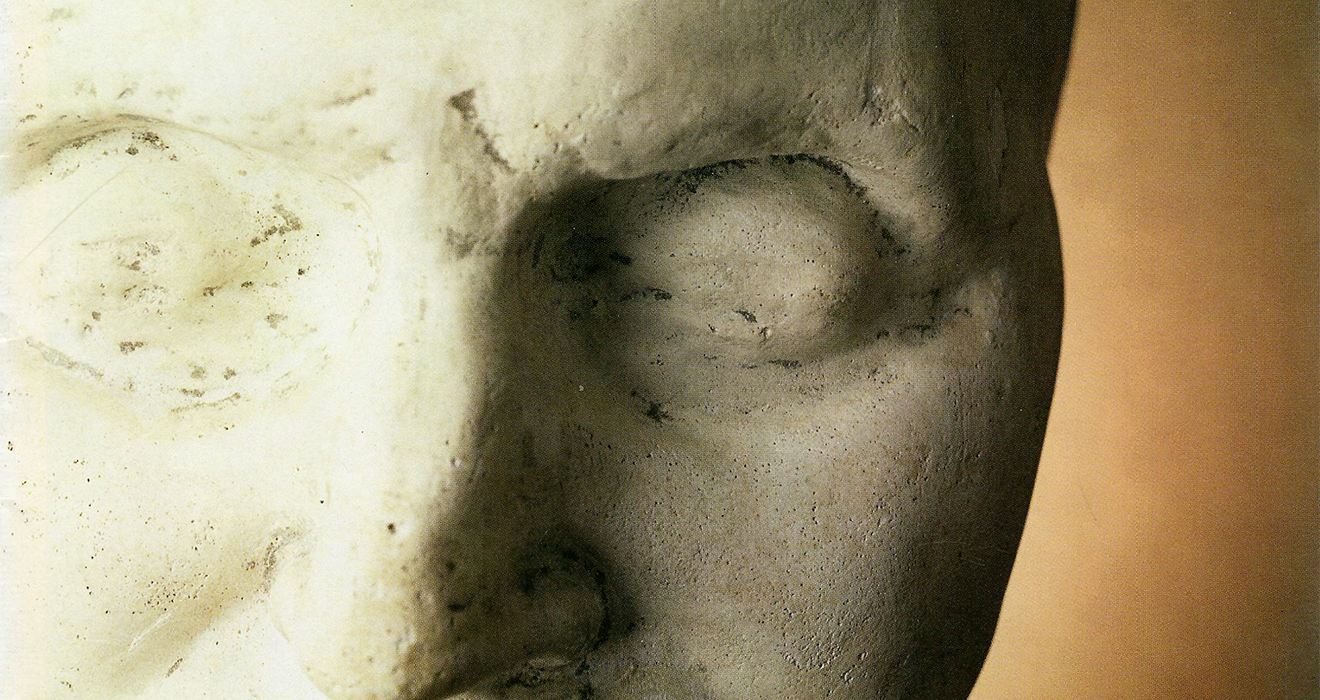

My eyes are six inches from Abraham Lincoln’s nose. It’s late 1860, just a few months before the start of the Civil War, and his expression is inscrutably grave. The lines in his face, particularly around his mouth, are so deep that I can practically lay my finger down in them, and his cheeks are stretched tight enough that I can see the clear outline of his skull and jawbone. Still, there is animation in his expression, and I can’t shake the feeling that the face is alive. Only his vacant eye sockets and his ghostly, chalky-white pallor give him away. I am staring at a mask.

One hundred and thirty-eight years ago, Abraham Lincoln pressed his face into a tub of wet plaster so deep that the gooey mixture covered even his ears. After a moment, Lincoln began to slowly wiggle his face out of the mold, finally emerging minus a few eyebrow hairs and with small, white pieces of plaster still clinging to his cheekbones. Unfortunately, history does not record whether the great orator had a suitable quip for the occasion. Later, once the mold dried, an assistant used it to make several “life masks” of the President-elect’s face for the National Museum.

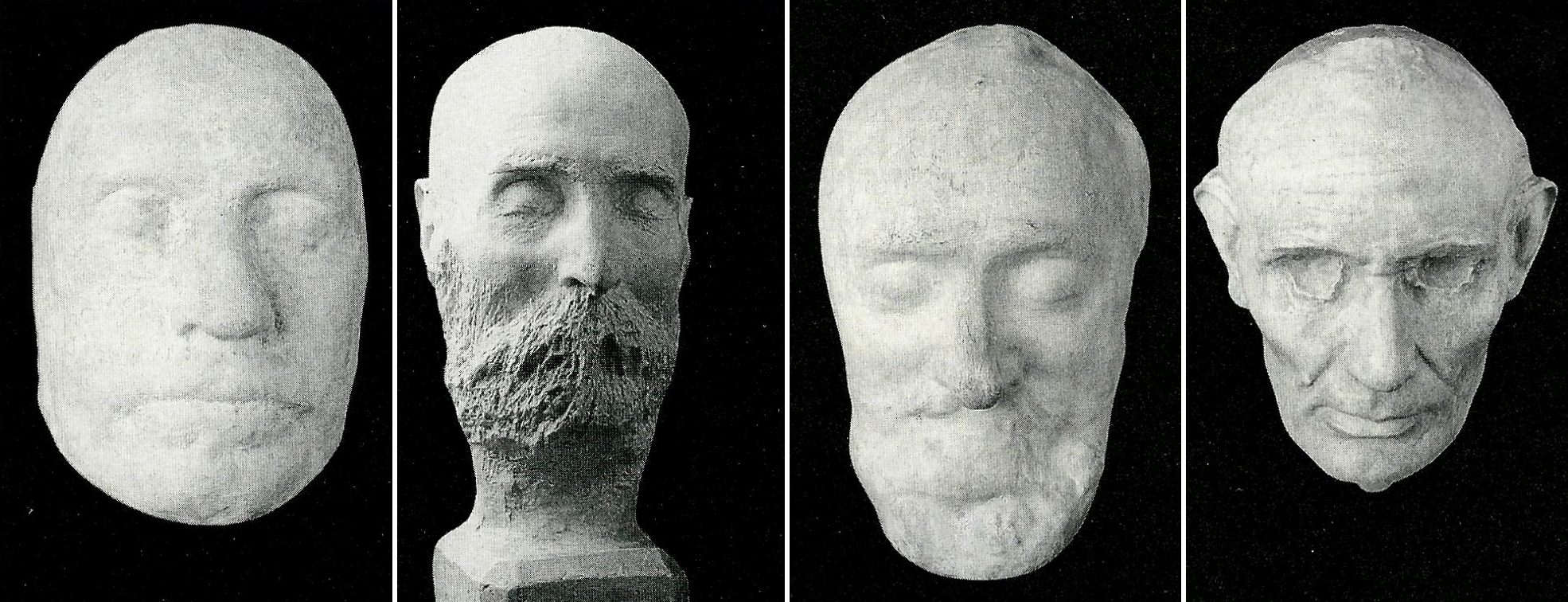

Today, one of the Lincoln masks is part of the Laurence Hutton Life and Death Mask Collection in Firestone Library: arguably the finest collection of life and death masks in the world. The collection, which consists of more than 100 masks, includes images of Aaron Burr 1772, Charles XII, Henry Clay, Oliver Cromwell, Benjamin Franklin, Frederick the Great, Goethe, Jean Paul Marat, Napoleon Bonaparte, Thomas Paine, William Shakespeare, William T. Sherman, Jonathan Swift, Daniel Webster, Walt Whitman, and Woodrow Wilson 1879.

In the early 1950s, the collection enjoyed a brief moment in the limelight when Life magazine published an article, entitled “How Great Men Really Looked,” that featured 16 photographs of the masks. After the Life article, the disparate worlds of pop culture and deep academia briefly touched, and the library received a flood of letters inquiring about the collection. Several people offered to sell death masks to the library — including one of James Dean — but the curators politely declined.

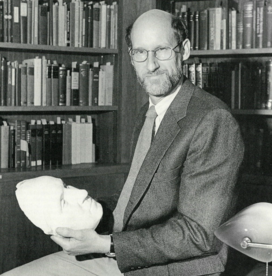

In the years since the Life article, the masks have been largely forgotten. John Bidwell, the current curator of graphic arts, can’t recall a single request to see the masks in the three years he’s worked at the library. “But,” he explains, “that’s how a research library works — you hold things until they suddenly come back into fashion. Perhaps someone will come in here next week and write a book about the masks, and then maybe nobody else will see them again for 50 years. But maybe 3,000 people will read the book.”

OF MASKS AND MEN

I didn’t feel like waiting for the book, so on a quiet Thursday morning I went over to the Special Collections section of Firestone to see the masks. The process was surprisingly painless. After I registered at the front desk, a librarian escorted me into the Dulles Reading Room, where I filled out a slip requesting the Abraham Lincoln mask. A page took my slip and brought me a large cardboard box with a small, neatly printed label that read, “Lincoln, Abraham and Henry IV.” The vagaries of cataloguing make for strange boxfellows.

After I was finished with Lincoln, I pulled Henry IV of France out of the box and placed him on a piece of green foam which the page had brought. As there was something too eerily macabre about having two disembodied heads floating on the foam, I moved Lincoln back into the box. Unlike Lincoln’s, Henry’s mask was a death mask, meaning (as perhaps should be self-evident) that it was made after he died. Most casters preferred to make the masks as soon as possible after death so that the autopsy wouldn’t distort the subject’s features. Henry’s mask, however, has a creepier history. Although Henry died in 1610, the mask in the Hutton collection was made almost 200 years later, in 1797, during the desecration of the royal tombs at Saint-Denis by French revolutionaries. When the desecrators exhumed Henry’s body they discovered it was almost perfectly preserved — and somehow they had both the stomach and the gall to make a mask.

The vast majority of the collection resides in boxes like the one that contains Lincoln and Henry, but six masks are on permanent display in the Scribner Room, on B floor. On my way down to see them, I stopped in the stacks to read about Laurence Hutton. He was born in 1843, the son of a wealthy Scottish merchant, and early in his life he fell in love with literature and the arts. While he wrote some travel books and served as literary editor of Harper’s magazine, the paw of June 18, 1904, remembers that he “had not so much a genius for authorship as he had for making and keeping friends ... Probably no man alive today has as many [friends] among American and English creators of things beautiful.”

Because of those friendships, Hutton’s house in Princeton was a treasure-trove of literary memorabilia from the late Victorian period. He had a huge collection of autographed and annotated books, photographs, scrap books, and letters (including 61 from Mark Twain). And, of course, there was his abiding passion — the masks.

Hutton, who for a time was a lecturer in English literature at Princeton, stumbled onto his collection in the early 1860s while poking around a bookstore in New York. A young boy came into the store with a death mask of Benjamin Franklin and asked the proprietor if it was worth anything. Hutton asked the boy where he’d found the mask, and he replied, “Over on Second Street in an ash bin. There’s a lot more there.” Hutton, his curiosity aroused, paid the boy to take him to the bin, and when he dug around in the ash he found five more masks that became the beginnings of his collection.

Just as important to Hutton as the masks themselves were the tales associated with their discovery. Every mask had a story. There was the Newton mask, which Hutton purchased “for five shillings and a quart of beer.” There was the Swift mask, perhaps the most valuable mask in the collection because it is the most rare, that was reported “broken” at Trinity College, Dublin, yet somehow showed up in a little store in London. Hutton remembered, “I bought the mask from a little dealer in plaster casts whom I never found at any hour of the day or evening in a condition of perfect sobriety. He could never explain how he became possessed of it, and he did not even know whose mask it was.”

The Swift mask is one of the six on display in the Scribner Room. The exhibit, located in a small alcove and partially hidden by a bookcase, contains no mention of Hutton or his passion. The six masks are of literary giants: Keats, Swift, Sterne, Whitman, Coleridge, and Wordsworth. Without any accompanying description, the masks appear to be just poorly sculpted busts — although no sculptor would render Swift so meek or Whitman so saintly. The small printed cards identifying the masks are in an archaic font and yellowing with age, and the whole display looks like something long forgotten.

Every couple of years the library uses one of the masks when it opens an exhibition on an individual in the collection. Ostensibly, that’s their purpose. “The reason you have graphic arts in a research library is to help evoke something of a figure you’re portraying, to make the book collection come alive,” Bidwell says. “Do the masks do that? Perhaps.”

LINKS TO THE PAST

Some other pieces of Hutton’s collection certainly do a wonderful job of making books come alive. Poking around in his letter collection, I found a postcard to Hutton from Mark Twain. The body of the card was one, breathless, 129-word sentence that concluded, “amen Mark. This letter to be mailed surreptitious. Too much editing don’t do no letter no good.” Reading that postcard made it far easier for me to imagine the kind of mischievous personality that could write Huckleberry Finn.

Do the masks serve the same function? That is the seven-million volume question in a library where every available cubic inch of space is needed to store an ever-expanding collection of disparate materials. In fact, some librarians seem downright hostile toward Hutton’s gift. As one who preferred I didn’t write this article said, “The library is not about strange or amusing things. We’re not a dumping ground for curiosities.” In his opinion, an article on the masks publicizes a relatively trivial collection while other, more valuable collections remain in dire need of money to catalogue and digitize them.

The Hutton Mask Collection is probably the largest and most comprehensive collection of its kind in the world, which is not, in and of itself, a reason to keep it. I could give the library the world’s largest collection of used running shoes, and the curators would be quite justified in immediately throwing them away. But the masks are in a gray area — potentially useful, yet largely forgotten. Would it be disrespectful for Princeton to give the collection away to an institution that has the space to permanently display the masks? Is there an institution that would want them?

What will forever separate the masks from the junk at the bottom of my closet (that is, unless the Red Sox teams of the early ‘90s suddenly come back into vogue) is that the masks once attracted a substantial amount of public attention. Perhaps some of that power remains. While I was looking at the Lincoln mask in the Dulles Room, several of the librarians crowded around me to get a closer look. And why not? We obsess over our public figures today, buy magazines with their pictures, and send hordes of photographers scurrying after them. We rarely tire of their faces.

But what of those famous figures who lived too early to be stalked by paparazzi? Photographs of Abraham Lincoln do exist, but none of those stiff portraits has ever struck me with the gripping immediacy of the mask. Perhaps the masks are just memorabilia, and maybe collecting memorabilia isn’t the business of a serious library. But the masks are also a tangible link to the past — objects that some people can use to relate to a time when the faces of the famous were not collected and indexed on CDs, the World Wide Web, and the pages of innumerable publications.

Around the turn of the century, an old man knocked on Hutton’s door in Princeton and asked to see his collection. The man browsed through the shelves until he came to a mask that Hutton had tentatively labeled “Aaron Burr?” The old man asked why there was a question mark after the name, and Hutton replied that he couldn’t confirm the true identity of the mask. “It is Aaron Burr,” the old man said firmly. Hutton asked how he could be so sure, and the old man replied, “Because in 1836 I took a rowboat out to Staten Island the night after his death and helped make this mask.”

Hutton, almost a century ago, used to love to tell that story at dinner parties, and he’d always conclude with the same punch line. “And thus,” he’d say, “I was able to assure the University of Princeton that Burr had come back to his alma mater.”

Where he lives in a box.

This story appeared in the Dec. 16, 1998, issue of PAW.

No responses yet