Issue in doubt

After 65 years, a Princeton family has guarded hope that a loved one’s remains might come home

On paper, the November 1943 battle for Tarawa should have been no contest.

An atoll in the Gilbert Islands about 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii, Tarawa stood at the gateway of the U.S. “island-hopping” drive through the central Pacific toward the Philippines and ultimately toward Japan. An American invasion armada that included 17 aircraft carriers and 12 battleships shielded 35,000 troops, who faced fewer than 5,000 Japanese. In previous amphibious assaults, the United States had not faced serious opposition from the Japanese on the initial landing. But at Tarawa — now known as the Republic of Kiribati — a well-armed, deeply entrenched Japanese force fought almost to the last man, and the United States made crucial mistakes, including poor tide calculations that left Marines struggling to cross 500 yards of reef under fire.

For three days, both sides fought ferociously. And by the time it was over, more than 4,000 Japanese and 1,000 Marines were dead, including Lt. Alexander “Sandy” Bonnyman Jr. ’32. He was one of four Marines to win the Congressional Medal of Honor, three of them posthumously, for their actions during that battle.For decades, the whereabouts of Bonnyman’s remains have been in doubt. Tarawa is no Normandy, with graves laid out neatly in U.S. military cemeteries. On this overcrowded, trash-littered Pacific island, construction projects routinely pull up parts of bodies. The Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office maintains that Bonnyman’s body was “non-recovered.” The official Navy Web site has listed him as buried at sea; an authoritative book about the battle, Utmost Savagery , says his body lies in Oahu’s Punchbowl, the National Cemetery of the Pacific; and his Marine casualty card lists both a temporary grave used immediately after the battle and a “memorial” grave with a marker but no body.

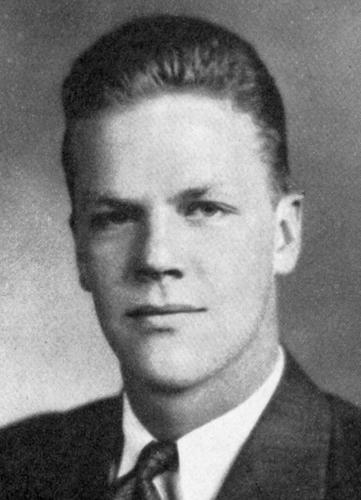

But last November, researchers from the volunteer organization History Flight reported that they had determined the location on Tarawa of the remains of 139 of the 541 U.S. Marines whose bodies never were found, including those of Sandy Bonnyman. Mark Noah, the executive director of History Flight, says that Bonnyman’s body most likely lies under a dirt parking lot. Another private researcher, William Niven, has overlaid Google Earth maps and photographs on the invasion maps and concluded that the remains of Bonny-man and 39 other Marines are located in a different spot nearby, “just southeast and just inland of the old pier the Marines fought so hard to take.” And now, 65 years after Sandy Bonnyman’s death, family members have guarded hope for a U.S. government search that could lead to a proper burial.Sandy Bonnyman lived a restless life, residing in Georgia, Tennessee, New Jersey, Texas, and New Mexico. He was born in Atlanta but grew up in Tennessee, where his father, also named Alexander, was president of the Blue Diamond Coal Co. in Knoxville. Bonnyman moved to New Jersey to complete high school at the Newman School in Lakewood before entering Princeton in 1928, becoming the first of at least six Bonnymans to attend Princeton.

“Sandy was a very handsome guy, a pleasure to be with,” says his 99-year-old classmate John Harmon ’32, who still goes to work in his investment office in suburban Chicago twice a week. “We ate lunch in Commons and talked about women.”

Bonnyman lettered in football and studied engineering, although “studied” may not be the right word to describe his time on campus, and he left Princeton after his sophomore year. Harmon recalls that after the crash of ’29, many young men left because their parents no longer could afford to send them to Princeton. But this was not what happened with Bonnyman. His oldest daughter, Fran Evans, now 74, says her father “had a math class he was supposed to finish, and left instead.” Harmon says Bonnyman wanted “to go to the service. He loved Princeton, but he wanted to do something for his country.”

And that’s what he did. After leaving Princeton, Bonnyman entered the Army Air Corps as a Flying Cadet in June 1932. But he lasted only three months after being sent to the Preflight School at Randolph Field in Texas and was honorably discharged. Explanations about why vary — he either “couldn’t fly in formation, or he buzzed the towers,” his daughter says. It was during his time as a cadet that he met Josephine Bell of San Antonio at a debutante party; they married in February 1933, while Bonnyman was working for his father in the coal-mining business. In 1938 he acquired his own copper mine in the mountains of New Mexico and moved his growing family, which by 1941 included three daughters. Evans remembers a tall man who took his daughters to church on Sundays and “played tennis and had bird dogs and would go out and shoot.” One Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, Fran watched him as he listened, agitated, to news on the radio about the attack on Pearl Harbor.

As a 31-year-old parent and worker in a war industry, Bonnyman could have qualified for a draft exemption. Instead, he joined the Marines as a private in July 1942. There was no long farewell to the family, though he would write letters and send postcards from his postings and would send a dollar when Fran told him that she “could do three chin-ups in a row.” This time, his military service began well; he served in combat during the 1942–43 Guadalcanal campaign, and in 1943 received an unusual field promotion to lieutenant. Months later, Bonnyman was on his way to Tarawa.

Leon Cooper, 89, the writer and producer of the Military Channel documentary Return to Tarawa, was in November 1943 a young Navy ensign ferrying Marine assault troops to Tarawa’s beaches. After his early-morning “battle breakfast” on Nov. 20, the Navy began bombardment of the atoll. Landing craft dropped from the troopship, and the Marines scrambled into Cooper’s Higgins boat. The Japanese were waiting. “The guys were throwing up during the trip from fear and seasickness,” Cooper says. “In the smoke and explosions, I couldn’t see a damn thing. There were a number of boats hung up on the reef. I do remember landing, and that’s when I saw scores of these guys being cut to pieces. I had 30 guys in my boat; only half made it to the sea wall. There were wrecked boats all over.” A high-ranking Marine officer watching the events radioed for reinforcements, ending with the ominous words: “Issue in doubt.”

Once the surviving Marines reached the beach, they confronted a network of Japanese pillboxes, snipers, and artillery fire. Bonnyman was executive officer of the Second Battalion Shore Party, Eighth Marines, Second Marine Division, and he did not have direct combat responsibility. Nonetheless, he took on a leadership role in the chaos, assembling and leading an ad hoc assault team, as shown in the 1944 documentary With the Marines at Tarawa. “He was a good, likable guy, but he took no guff,” remembers Leroy Kisling, 85, of Modesto, Calif., then a sergeant who served with Bonnyman as a demolition man on Tarawa. He recalls Bonnyman as a generous man who would share his officer’s liquor ration with the noncommissioned officers. “Wading into Tarawa, we all had our hands full. ... One of the guys had a mine detector and he thought it was too heavy, so he dropped it into the ocean. Bonnyman threatened to send the guy back under enemy fire to get it. His attitude was, ‘You’ve got a job to do; you’d better do it.’ ”

Bonnyman’s team attacked strongly defended enemy emplacements, including the pillbox where he is believed to have been killed. Fran Evans has seen With the Marines, which contains the last images taken of her father. “It’s just a helmet and a tall man on top of a hill.” The movie would win an Oscar as best short film; its indelible images of dead Marines floating in the surf sparked a storm of protest. According to one officer, the film temporarily cut Marine recruiting by 35 percent.

Originally awarded the Navy Cross, Bonnyman later was deemed worthy of the nation’s highest military honor. The Medal of Honor citation provides details of the events: “Acting on his own initiative when assault troops were pinned down at the far end of Betio Pier by the overwhelming fire of the Japanese shore batteries, 1st Lt. Bonnyman repeatedly defied ... the enemy bombardment to organize and lead the besieged men over the long, open pier to the beach and then, voluntarily obtaining flame throwers and demolitions, organized his pioneer shore party into assault demolitionists and directed the blowing of several hostile installations.”

The next day, the citation continues, “he voluntarily crawled approximately 40 yards forward of our lines and placed demolitions in the entrance of a large Japanese emplacement ... in his planned attack against the heavily garrisoned, bombproof installation. … He led his men in a renewed assault, fearlessly exposing himself to the merciless hostile fire as he stormed the formidable bastion, directed the placement of demolition charges in both entrances and seized the top of the bombproof position, flushing more than 100 of the enemy who were instantly cut down, and effecting the annihilation of approximately 150 troops inside. Assailed by additional Japanese, he made a heroic stand on the edge of the structure ... in the face of the desperate charge, killing three of the enemy before he fell, mortally wounded.” He was 33.

Marine historian Col. Joseph Alexander wrote that Bonnyman’s action “almost single-handedly ended the stalemate on Red Beach Three.” More prosaically, the late Harry Niehoff told Bonnyman’s daughter Alix Prejean, now 68: “I hope you don’t mind that I used your father’s body as a shield.”

Fran Evans learned of her father’s death while on a vacation in Fort Lauderdale: The man who would become her stepfather “showed up and took me deep-sea fishing with my mother,” she remembers. “That’s where he told me my father had been killed. That was horrible. Horrible.” Ever since, she says, she’s hated deep-sea fishing. Her mother quickly remarried, and the daughters were split up temporarily. Bonnyman’s parents — Fran Evans’ grandparents — were heartbroken. “Grandfather Bonnyman wrote letters to everyone to find remains to send back,” recalls Evans. “I don’t remember what they told him, but we got a marker with the name Bonnyman, which was misspelled” as “Bonneyman.” Sandy’s brother, G. Gordon Bonnyman ’41 — who fought with Merrill’s Marauders in China, Burma, and India and was awarded the Silver Star, the Bronze Star, and the Purple Heart after being critically wounded — would recall the letter containing news of Sandy’s death as his worst moment of the war. “If you raised that with him as an older man, he would start crying,” says Gordon’s son, G. Gordon Bonnyman Jr. ’69.

In 1947, with her mother remarried, 12-year-old Fran was drafted to accept the Medal of Honor from Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal ’15. She took a train from Santa Fe to Washington, D.C. Her grandfather was there, along with some of her father’s Princeton classmates. She wore a suit and coat and “horrible loafers,” and a hat. When Forrestal gave her the medal, she says, “I was struck silent. It was very solemn and quite beautiful.”

The military told family members after the battle that Sandy Bonnyman had been “buried at sea,” and those words are etched on his memorial in the family plot in Knoxville, Tenn. But not everyone believed it. Sandy’s brother Gordon, who died in 2004, believed that in the chaos and confusion, a bulldozer had dug mass graves for his brother and other Marines. Gordon Bonnyman had a “pretty brutal idea of what actually happened; he was quite cynical about the glorification of war and its ritual,” says his son.

In fact, Gordon Bonnyman’s view probably was close to the truth. The Marines buried their dead quickly after the battle, placing markers with the expectation that the remains could be reburied under better conditions. But the markers are believed to have been lost during war construction, including the widening of airstrips. Since then, construction projects by residents of the islands also have covered — and occasionally uncovered — the graves.

An Army graves-registration unit that came to the island in 1946 succeeded in identifying and repatriating fewer than half of the 1,000 bodies of Americans to the United States. Annette Amerman, a historian with the Marine Corps, says it was common for Marines to be “buried in a temporary grave and moved after the site has been secured.” A Marine field board determined at the time that Bonnyman’s remains were “non-recoverable.” Could they be recovered with today’s technology? “The U.S. is doing more than any country in the world for its war dead,” Amerman says. “But of course, there are limits.”

After World War II, thousands of people from surrounding islands came to live on Tarawa, and today the island — about the size of New York’s Central Park — is home to about 40,000. “It’s one of the most isolated countries in the world,” says Simon Donner, an assistant professor of geography at the University of British Columbia and a former research scientist at the Woodrow Wilson School. “People live in huts made of thatch, concrete, and sheet metal that don’t have proper garbage disposal, and half don’t have toilets.”

There have been numerous reports of bodies being unearthed in Tarawa. Donald Allen, who wrote and self-published Tarawa: The Aftermath, says “the whole island is, in fact, a cemetery,” with buildings constructed over gravesites. In his 2004 account of living on Tarawa, The Sex Lives of Cannibals, J. Maarten Troost wrote about the corpses found when new wells are dug. In Goodbye Darkness (1980), William Manchester told of the official who “has to handle the delicate consequences of finding the skeletons of fighting men, which are discovered from time to time when new sewer lines are laid, or when children are building sand castles around old spider holes. Last week, a group of little boys unearthed the fleshless corpses of four Japanese and one American. How, I ask, can he tell the four from the one? It is easy, he replies; the American was wearing dog tags and a Swiss watch, and Japanese femurs, teeth, and skulls are microscopically different from ours.”

In 2000, the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory acquired and investigated “human remains and multiple artifacts” discovered by construction workers on Tarawa. The identification tags belonged to Pharmacist’s Mate Raymond P. Gilmore and Pfc. Darwin H. Brown. Brown’s remains later were buried in his hometown of Bernardston, Mass.; his sister, Beulah Denison, said it was “an amazing relief” to be able to say goodbye.

Will Bonnyman’s family say a similar farewell? Following research begun in 1992 by Marine veteran Ted Darcy, and relying on the Marine Corps’ original casualty card, Mark Noah of the Florida-based History Flight organization says Bonnyman is “buried in grave No. 27 at 8th Marine Cemetery No. 2, at Red Beach on the island. This particular site is a dirt parking lot, next to a garbage dump.” The group’s ground-penetrating radar and archival research — out of respect for the war graves, there was no digging — have confirmed the presence of bodies at the site, Noah says. History Flight is completing a report to present this year to the U.S. government.

Nephew and Navy veteran Al Bonnyman ’78, general manager of a fiber-optics company, is hopeful but skeptical. “I’ve used ground-penetrating radar; you just know something’s down there. It’s like when you have kids and you look at their ultrasound; the obstetrician is going, ‘There’s the head, there’s the elbow,’ and you just see a blob.”

Even if the bodies physically could be recovered, it’s not clear that anything will be done. According to Marine spokesman Lt. Joshua Diddams, “As far as the prospect of searching Tarawa for more remains, that is a decision which needs to be made between the State Department and the government of Kiribati,” a sovereign nation. The Marine Corps is not involved in the decision, he says.

Recovery missions are conducted by the Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), whose motto is: “Until they are home.” The command has an annual budget of $50 million, 400 civilian and military team members (including linguists, anthropologists, explosive-ordnance technicians, medics, and mortuary-affairs specialists), and the largest forensic-anthropology laboratory in the world. The command grew out of efforts begun in the 1970s to recover those missing in Southeast Asia, and most of its attention has gone to recover soldiers lost during the Vietnam War; JPAC’s Lt. Col. Wayne Perry acknowledges that’s because those families have been the most vocal.

Despite its resources, JPAC has an overwhelming mandate. To date, the bodies of more than 1,400 Americans have been identified, and JPAC’s lab identifies an average of six people each month, according to its Web site. But many more are still missing, including 1,800 from Vietnam, 8,100 from the Korean War, and 78,000 from World War II — of whom 35,000, not including Bonnyman, have been deemed “recoverable.” This year, JPAC is conducting more than 50 investigation and recovery missions in places like the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Vietnam, South Korea, Cambodia, and Germany. Tarawa is not on the list, but Perry says JPAC can add missions if enough credible evidence is found. “If remains were found by private groups, or if the site were in imminent danger of being destroyed by weather or construction, it becomes a site we want to get to right away,” he says. “We’re tracking the Tarawa losses, but other missions have a higher priority because they have verified remains.”

JPAC historian Heather Harris says the cases of Bonnyman and other Tarawa Marines and sailors are unusual because of the “complicated nature of the initial battle and burials and then the series of reburials by different [military] services and units.” A 1946 report says that the area where Bonnyman was believed to have been buried was searched extensively, she notes, and “this information, combined with our research indicating development of the area of original burial and extensive land reclamation in the vicinity of the pier, serve as indicators that these burials, should they still be in place, will be difficult to locate.”

Retorts Mark Noah: “Someone’s not looking hard enough.”

Even at 89, Bonnyman’s fellow Tarawa veteran Leon Cooper musters a sense of outrage. “People lying where they fell is really a blot on our country’s institutional memory. This is our nation’s shame.” He has met with government ministers in Tarawa, and with senators and congressmen in Washington. So far, he says, nothing has happened: “They don’t give a damn.”

Today, JPAC is seeking DNA samples from family members of those whose bodies were not recovered during World War II and the Korean War. If a search is done and remains are found, Alix Prejean is ready. “My father had four gold dental implants. There’s also plenty of Bonnymans around; I’ve offered to give my DNA.”

“At first, I said, let sleeping dogs lie,” she says. “But it’s not only for my father. The Marines have this thing about not leaving anyone behind. It’s tragic that all those men are just left there in a garbage dump.”

Fran Evans is more philosophical. Over the years, she has christened a Navy ship named after her father, as well as a street in Knoxville and Bonnyman Bowling Center in Camp Lejeune, N.C. “In my old age, I feel sensitive; they don’t need to keep honoring him,” she says.

She has made peace with the situation. “Our grandparents would have been thrilled to have his remains returned to the U.S., but it has been over 60 years ... . ” If her father’s remains are found, she thinks, she would like them to be buried in “the beautiful cemetery in the Punchbowl in Honolulu,” which already has a memorial to him. Still, she believes Sandy Bonnyman would be happy “wherever he is.”

In the meantime, “it would be very honorable and nice to put up a memorial,” she says, “on the parking lot.”

Michael Goldstein ’78 is a Los Angeles-based writer and winner of two Los Angeles Press Club awards. This is his second piece for PAW.

2 Responses

Louis Sanford ’63

10 Years AgoHeroism at Tarawa

Michael Goldstein’s piece, “Issue in Doubt,” recalling the battle of Tarawa, struck a deep chord. My uncle, Gordon Hildreth ’42, was a Marine lieutenant who was among the first 400 men in the first wave of landing forces in that bloody battle of November 1943. Although he never spoke of his experience, my grandmother (his mother) related that her son witnessed the deaths of two of his best buddies as they were mowed down near him en route to the beach. Gordon, known to the family as “Bud,” did share with me that he was a proud member of the 2nd Marine Division (Reinforced). I’ve since learned that the division received a presidential unit citation for its heroism and ultimate victory at Tarawa.

Typically modest, Gordon never mentioned his two Purple Hearts, earned later at Saipan and Tinian in the Marianas (June and August of 1944, respectively). And it was his mother who informed me that — according to one of his compatriots — in one of those battles, my uncle gave up his sickbed to a Marine who was, in his opinion, more severely injured.

In my own service in the Navy as a lieutenant junior grade on a rocket- firing ship (LSMR 525) in Vietnam, I often took heart in remembering Gordon’s bravery and modest demeanor. Bud died in 1989, but he will always remain a hero to me.

Kenneth E. Scudder ’63

10 Years AgoThe battle for Tarawa

Thanks to PAW and to Michael Goldstein ’78 for his article (cover story, May 13) on the search for the remains of Alexander Bonnyman ’32, lost in battle on Tarawa atoll in 1943. It’s a saddening testament to the senseless futility of war that so many men died fighting over such a tiny and insignificant spit of land. I was reminded again that if my father, an Army colonel (West Point ’28), had gone to war a little sooner and had not survived, I would not be here.

Perhaps the most fitting commemoration of the great loss that was Tarawa would be to establish a joint American-Japanese commission to try together to locate the dead from both armies, to bring the families of both the survivors and the dead together, and to create a simple, common memorial to all of the fallen there. Attention must be paid.