Over beers at a watering hole in downtown Leeds, England, Jesse Marsch ’96 ponders a question that, truth be told, he probably would prefer not to answer. When Marsch took over as the head coach at Leeds United earlier this year, he became the second U.S.-born field boss of an English Premier League team — his college coach at Princeton, Bob Bradley ’80, was the first — and last summer Leeds spent $54 million to sign two young U.S. stars, Tyler Adams and Brenden Aaronson.

Never have so many Americans held such prominent roles on the same team in the world’s most popular domestic soccer league. For the most part, the English have been famously dismissive of Americans in “their” sport, and there is still a resistance to the wave of U.S. owners in the English game. Hence the question: Rightly or wrongly, will the performance of Leeds United be a referendum on Americans in the Premier League?

Marsch hems and haws for a bit. But unlike a lot of Premier League managers, he has a reputation for actually answering the questions he receives.

“I care so much more about just the team,” Marsch finally says. “I don’t have an attachment to the history of what this means, and I was a history major,” he laughs. “When I first came, I tried to reiterate that there wasn’t an Americanization of Leeds United. It’s harder to make that case after two American transfers, and with the [NFL’s San Francisco] 49ers being part of the ownership group.”

“But the beauty is, we have an Italian owner, an English CEO, a Spanish sporting director, an American manager, and then a couple of American owners who, by the way, I didn’t meet until two weeks before I took the job. And in training, I have an American manager, an Austrian assistant, an English assistant, a Welsh assistant, a French fitness coach, and a Spanish goalkeeper coach.”

Not only is the Premier League the planet’s most cosmopolitan sports league, but its unparalleled television revenue means it also has a large number of the world’s most revered coaches, including Manchester City’s Pep Guardiola, Liverpool’s Jürgen Klopp, and Tottenham’s Antonio Conte. Marsch, who grew up in Racine, Wisconsin, and won nine trophies in a 14-year Major League Soccer playing career, is now one of 20 Premier League managers, all of whom are under so much pressure that a half-dozen or more could lose their jobs this season. But the benefits if you succeed are just as large as the potential pitfalls.

“As a coach, you’re challenged at this level by all the geniuses in the sport and what they do, and you’re tested to see: Can you be as good on a day?” Marsch explains. “You have a weekly test. And with your teams can you manage to find a way to emerge? And there’s a lot that goes into success and failure in our sport — in any sport, in any business, I guess — but the challenge of trying to test yourself against the best and with incredible talent is a really enjoyable process for me.”

By the time of the September international break, Marsch had steered Leeds to a promising 3-0 victory over Chelsea, and his club had a mid-table position in the Premier League, several places above the relegation-zone battle that he had walked into when he took the job in February before clinching safety on the last day of last season. (The bottom three teams in the Premier League are demoted to the next-lower division, called the Championship, while the top three teams of the Championship are promoted to fill those spots the next season.)

“After the game, we celebrated like we won the league, except there was no trophy,” Marsch says with a cackle. “I had more people congratulate me for finishing in 17th place than I think I would ever have in any realm of anything. As Americans, it’s like if you’re not first, you’re last. Well, I realized that 17th is sometimes like first.”

Marsch’s recent coaching influences have been international, largely from the six years he worked with the German figures running Red Bull’s global soccer operation. But he still maintains close ties to people from Princeton. From his current position managing Toronto FC, Bradley has observed his former player and assistant’s growth as a coach. “Jesse has done a great job of taking his playing and coaching experiences and thinking about them,” Bradley says, “and then turning that into how he wanted his team to play, how to implement ideas. Ideas on the kind of culture that he wanted to create and what his leadership style was going to be all about.”

Mitch Henderson ’98, who has been the Princeton men’s basketball coach since 2011, is one of Marsch’s best friends, someone who was on the phone with Marsch five minutes after the landmark victory over Chelsea. “I think his great gift is his relationship with people and players and families,” Henderson tells PAW. “Connecting with people is the thing that we probably talk about the most when we’ve got time.”

Over the decades, Miami University in Ohio became known as “The Cradle of Coaches,” a reference to the famous sports leaders who had roots there, including Bo Schembechler, Ara Parseghian, and Paul Brown. But most of Miami’s alumni have been football coaches. Princeton has produced one NFL head coach (Jason Garrett ’89), but in recent years, the University has become its own Cradle of Coaches in two other sports: soccer and basketball. And there is no better representation of that than the bond of Marsch and Henderson.

Pete Carril, the legendary princeton basketball coach, died in August at age 92. During his 29 years coaching the Tigers, from 1967-96, Carril had a massive influence on his sport through his innovative Princeton Offense (which spread to high school, college, and NBA teams) and through his coaching tree of acolytes who moved to destinations throughout the basketball firmament. Bradley, who was the Princeton soccer coach for 11 years, from 1984-95, developed his own coaching tree from his days leading Princeton, the Chicago Fire, the U.S. men’s national team (which he led at the 2010 World Cup), and nine other head jobs on his soccer journey.

Two of the most prominent branches on the Bradley and Carril coaching trees are Marsch and Henderson. “I love the term Cradle of Coaches,” Henderson says. “It certainly applies to the men’s basketball side here at Princeton with Coach Carril’s influence. And the influence Bob had feels similar to the way Coach Carril influenced us. That’s the connection.”

Henderson and Marsch had met during their days as students on campus, but they became best friends in Chicago, where Marsch played for Bradley, and Henderson was former Princeton coach Bill Carmody’s assistant at Northwestern. Henderson moved a few blocks from Marsch and his wife, Kim, and they hit it off. “I spent pretty much every free moment I had with them for years,” Henderson says.

They all lived in the same town again — this time in Princeton — when Henderson was the Tigers basketball coach and Marsch was between pro soccer jobs assisting the Princeton soccer program and then becoming the head coach of the New York Red Bulls. Henderson and his wife, Ashley, were a fixture at Red Bulls games, and when their third child, Archie, was born, they asked Jesse and Kim to be his godparents.

Henderson has visited Marsch over the years during his coaching stops in Germany (Leipzig), Austria (Salzburg), and now England (Leeds). Soccer and basketball don’t have a lot of overlap, both coaches concede, but some common areas exist. Player management is one of them, as is the case in all sports, and Henderson says he has learned plenty from Marsch on connecting even better with his players. Then there are the dead-ball situations that in soccer are called set-pieces and in basketball inbounds plays. Both coaches are now hailed as innovators of designed plays.

“He used to tease me when I would go to Chicago Fire games,” Henderson says. “I would say, ‘How come you guys don’t practice corner kicks like all day? And he would laugh and say, ‘You can’t do that.’ But as he got to be a coach, he started to think about different ways he could set things up, and his teams have been terrific with set-pieces. Now a lot of soccer teams are hiring set-piece coaches, and [those plays] are huge in basketball too.”

Let’s make something clear: I am not a neutral observer when it comes to Jesse Marsch. We’ve been friends since 1994, when we were both 20-year-olds who got sick and shared a room for a few days at Princeton’s McCosh Health Center. We watched that year’s Winter Olympics together on TV, and I got to know the guy I covered for the school newspaper on Princeton’s soccer team. If you had told us that 28 years later I’d be a soccer writer interviewing Marsch in England for a story on him coaching a Premier League team, we both would have laughed you out of the room. MLS hadn’t even started yet, and nobody (not even Marsch) thought he’d become a professional soccer player, much less a coach. And while I had a goal of writing for Sports Illustrated, I hoped I’d be covering basketball — not soccer, in which the U.S. media had shown next to no interest for decades.

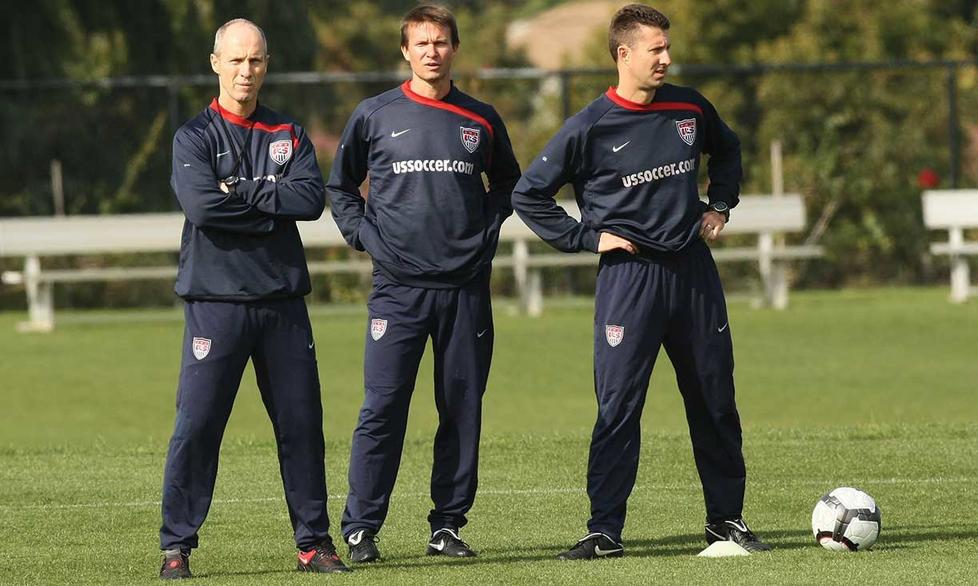

Yet somehow we both made it here. Over the years, I was in the stadium for Sports Illustrated for some of Marsch’s biggest moments: when his Chicago Fire, coached by Bradley, won the 1998 MLS Cup as an expansion team; when Marsch kicked England mega-star David Beckham in the midsection and started a melee in a 2007 game between Chivas USA and the LA Galaxy; when the U.S., with Marsch as Bradley’s assistant coach, won its World Cup 2010 group on Landon Donovan’s last-second goal against Algeria; when Marsch’s Salzburg came back from 3-0 down to tie Liverpool 3-3 in the UEFA Champions League at Anfield in 2019 — only to end up losing 4-3; and when Marsch got his first Bundesliga win during his short-lived tenure at Leipzig in the fall of 2021.

In the basement storage unit of my New York City apartment building, I still have a yellowed 1996 Daily Princetonian clip in which Marsch, who’d had a surprise All-America season his senior year, says he’s hoping to get drafted by a second-division U.S. pro team. But MLS was starting that year, and D.C. United — with Bradley as an assistant coach to Bruce Arena — selected Marsch with its last pick in the college draft. Marsch was just nine spots from being the MLS version of Mr. Irrelevant (the final pick of the draft), and he had a choice to make: accept a job offer to go into advertising in Chicago, or take a risk and become a pro soccer player.

“Bob convinced me to kind of gamble on trying to be a professional for a couple years, and he thought I could be good enough,” Marsch says. “My first contract was $6,750 with D.C. United, and then I had a developmental contract with [the minor-league affiliate] Hampton Roads Mariners. At the end of the year, I made a little over $40,000, so I lost money that year [in relation to the advertising offer].”

Marsch’s coaching preparation started in earnest in 2000. A mid-level European club offered him a playing contract that was slightly better than his MLS offer, but he and Kim, who were expecting their first child, decided to stay in Chicago. “So I re-signed with MLS on a really bad contract,” he says, “and I made the decision that I was going to be a coach.” He started doing the work to obtain his coaching licenses, and during MLS offseasons, Marsch would visit former American teammates in Europe — Brian McBride, DaMarcus Beasley, Sacha Kljestan, and others — to attend training sessions and speak to their coaches and sporting directors, taking furious notes all the while.

After retiring as a player in 2009, Marsch took a job as Bradley’s U.S. assistant for nearly two years and then spent one season as the head coach of the Montreal Impact of MLS. He departed with a mediocre record (12th-best in a 19-team league). “But it was probably the most important experience,” he says. “I had an idea in my head of what I thought the job was that I think was wrong, and I needed to learn about how to work with people and lead better. That’s when I really think I developed who I am as a coach and what my leadership ideas are and how to invest in people more.”

Yet more than two years would pass before Marsch coached another pro team. Not long after leaving the Montreal job, he and Kim had dinner with another couple who asked a question: What do you want to do? But they weren’t looking at Marsch. They were asking Kim. She and Marsch had been together since their high school days in Racine. “I was 16,” Marsch says. “I got my driver’s license on my birthday and asked her on a date two days later.” They married in 1998. Kim had been a social worker in Chicago until their second child was born in 2003. She answered their friends’ question: If there wasn’t a job to start for Jesse, who’d received severance from Montreal, then she’d love to travel. And so they did. Marsch and Kim pulled their three kids — daughter Emerson, then 11, and sons Maddux, 9, and Lennon, 5 — out of school and spent the next six months staying in hostels and visiting 33 countries, including Nepal, India, Vietnam, Egypt, and a host of European nations.

Upon returning to the U.S. in 2013, the family settled in New Jersey, where Marsch helped the Princeton men’s soccer staff while seeking pro head coaching jobs. “I was second in seven interviews in MLS,” he says, “and I was worried I would never find the right people again.” But his experience with the Red Bulls was different. After a promising phone interview, general manager Marc de Grandpre invited the Marsches to a dinner with him and his wife.

“I can handle it if you don’t get hired because of you,” Kim told Jesse, “but I can’t handle it if you don’t get hired because of me.”

“Honey, you can only help my chances,” Marsch replied.

The couples hit it off, and Marsch got the job. As part of the process, he spent time with Red Bull’s international soccer braintrust, including head of global football Gérard Houllier, director of football Ralf Rangnick, and CEO Oliver Mintzlaff. Marsch traveled to observe the training sessions of Leipzig and Salzburg, and Rangnick “explained to me the entire philosophy from A to Z,” Marsch says. “I almost couldn’t believe what they were describing to me at the time. It was so complex and aggressive tactically in so many different ways. But it fit me. I said: This is going to work.”

Marsch’s team became a force of nature. During his first season, the Red Bulls won the 2015 MLS Supporters Shield with the league’s best regular-season record, and they did it again in 2018. Marsch was there for only half of that campaign. In June of that year, Red Bull sent him to Leipzig, where he spent a year as Rangnick’s assistant. Then came two seasons as the head coach at Salzburg, where Marsch won the Austrian league and cup double both years and competed toe-to-toe with giants Liverpool, Bayern Munich, Atlético Madrid, and Napoli as the first American to coach in the Champions League. A Hard Knocks-style video of Marsch’s impassioned halftime speech in Salzburg’s wild 4-3 loss at Liverpool went viral in October 2019, replete with his F-bombs and half-German, half-English exhortations. (Marsch is still chagrined over its popularity, since he prefers not to be singled out.)

Last December, Marsch departed Germany’s Leipzig, the jewel of the Red Bull soccer empire, by mutual consent after just four months of games (and six years with Red Bull teams). There were too many losses. But he was also eager to leave. In a strange twist, Marsch was deemed “too Red Bull” for Red Bull, too pure in his all-out press-and-attack strategy for a team whose players had grown accustomed to possessing the ball. And from a vibes perspective, the energy-drink club was lacking the appropriate, well, energy. “The energy in Leipzig, I knew even from my time as assistant that it wasn’t right,” Marsch says. “And I tried to change it in Leipzig, but they weren’t interested in that. And to be fair, they’ve had great success before me and after me, so they don’t need me, and why should they have me there?”

“Energy” has become a commonly used word in the Marsch household over the years. “My wife always spoke about energies when we were younger, and I always asked her, ‘What the heck are you talking about?’” Marsch says. “But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve described things more the way that she did when we were younger. And energies to me is like, ‘What’s your gut feeling of situations, of people, of circumstances?’ And from day one, being here in Leeds, I’ve just always had the best feeling about the energy and the connection of what we’re doing here.”

Leeds is off to a good start in the Premier League season, but Marsch knows as well as anyone that job security is never a sure thing in this coaching gig. And as much as Marsch appreciates the situation in Leeds, sometimes even more enticing jobs can open up. Every American at Leeds hopes the U.S. does well at the upcoming World Cup, which could lead to coach Gregg Berhalter being retained for the 2026 cycle and a home World Cup. But it’s also possible that U.S. Soccer could be looking to hire a new men’s coach in January. If that’s the case, Marsch would easily be the domestic-born candidate of choice for U.S. fans.

“That job, it’s massively attractive,” Marsch allows. “Not now, and not six months from now. But I was in Salzburg 13 months ago, right? And lots happened. It feels like I’ve lived a lifetime in the last 13 months, so I would obviously never say no to the possibility of what it would mean to coach the national team. It’s just hard to picture where I’m at right now and that timeline for six months from now really fitting. Impossible.”

He’s right, of course. Yet it’s hard to imagine that Marsch won’t coach the U.S. at a World Cup someday, just as Bob Bradley did in 2010 with Marsch at his side, planting the seeds for a coaching tree that just keeps growing.

After writing at Sports Illustrated for more than 25 years, New York Times best-selling author Grant Wahl ’96 started his own subscription site covering soccer, GrantWahl.com, on Substack in August 2021. In Year 1, he wrote 30 magazine stories from 15 countries and attracted more than 2,700 paid subscribers, and is now making preparations to bring his premium coverage to the men’s World Cup (in November-December) and women’s World Cup (July-August 2023). Wahl also helped produce Good Neighbors, a three-hour documentary series on the U.S.-Mexico soccer rivalry premiering on Amazon Prime in November.

2 Responses

Dave Sherry ’86

2 Years AgoRIP, Grant Wahl

I never met Grant but always enjoyed the humanity and passion that came through in his writing over the last quarter century. He will be missed by many that loved his work and the man himself.

David Driver

11 Months AgoGreat Read by Grant Wahl

What a great story but that should not be a surprise. I wrote a book about American basketball players in Europe so this was really interesting to read.