Where Hate Hides

Joel Finkelstein *18, co-founder of the Network Contagion Research Institute, built an early warning system for the internet

On a 2018 United flight to South Florida, Adam Sohn, a broad-shouldered businessman, found himself sitting next to a lanky man transfixed to his laptop. Sohn’s eyes popped when he noticed what was on his neighbor’s screen — intricate word clouds with racist and antisemitic language. Words most people never think, much less leave visible on their computer.

Sohn was an open-minded guy. A former Wall Street trader who left that life after 9/11 and had since pursued an eclectic career working for the AARP, Jeb Bush, and Charles Koch, Sohn wasn’t afraid of going against the grain to do work he thought could make a difference. And in this case, he was determined to figure out if his airplane neighbor was a terrorist. “You look like a pretty smart guy,” Sohn recalls saying to the stranger. “But are you gonna crash the plane? Or maybe save the world?”

When Joel Finkelstein *18 told him what he was up to, Sohn was floored. Finkelstein was a neuroscientist whose research had led him to study how hate speech spreads on the internet. By tracking the proliferation of racial slurs and memes on far-right platforms such as 4chan and Gab, Finkelstein had discovered that hate speech activity spiked on social media before hate crimes and other attacks occurred, allowing him to anticipate events such as the 2017 Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally.

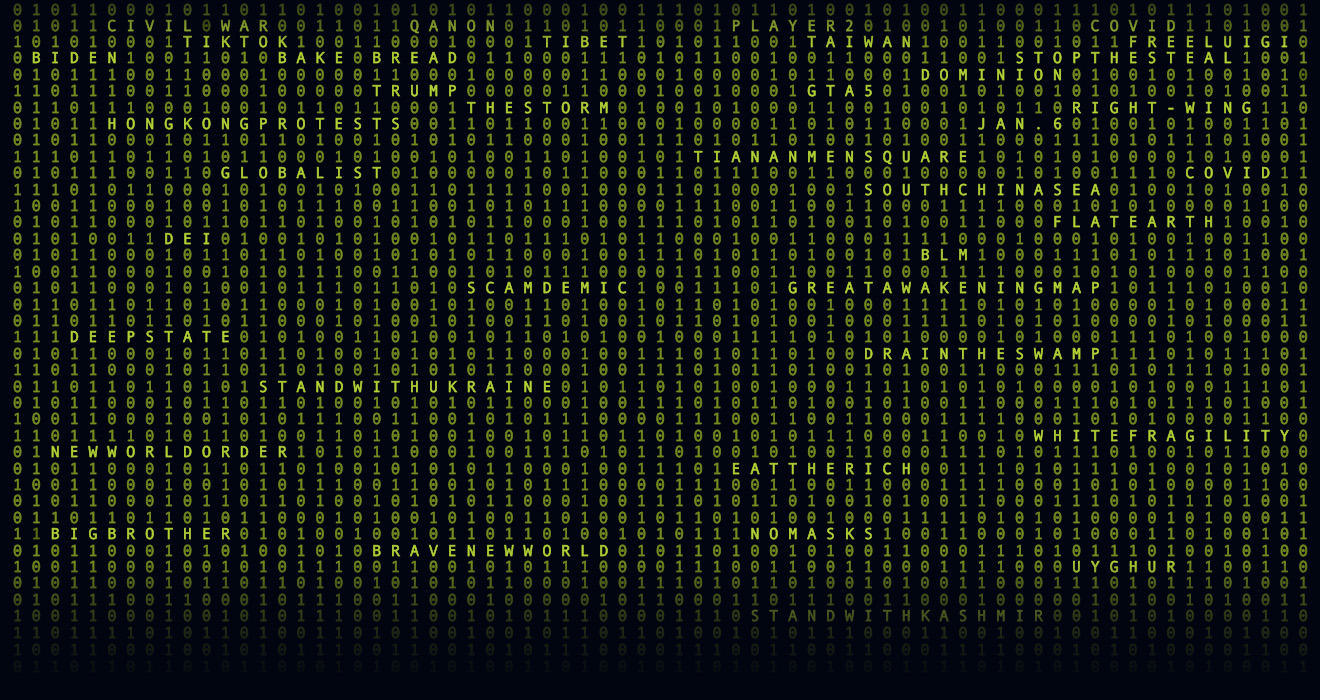

As Sohn heard this, he knew he and Finkelstein were going to be working together. A few months later, in May 2018, Sohn and Finkelstein co-founded the Network Contagion Research Institute (NCRI), a nonprofit research group based in Princeton, with Sohn its CEO and Finkelstein its chief scientist. Since then, the group has released white papers that have had an outsize impact on U.S. policy. A month before the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, NCRI’s December 2020 report on QAnon examined the conspiracy movement’s role in amplifying the false narrative that Dominion voting machines had rigged the 2020 presidential election in President Joe Biden’s favor. And when the dust settled on the Capitol riot, NCRI’s follow-up research informed the ensuing House investigation.

NCRI’s research interests range widely, from prompting the Apple app and Google Play stores to take down misbegotten dating apps for teens that served as the playground for Nigerian “sextortionists,” to understanding the extent of social media posts supporting Luigi Mangione, charged with the December 2024 murder of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson. Perhaps most significantly, NCRI’s work was invoked by Congressional leaders in the passage of the TikTok ban bill, entailing a forced sale or ban of the app that was affirmed by the Supreme Court and postponed three times by President Donald Trump — shortly after he took office in January, again in April, and then for 90 days on June 19.

NCRI is not without controversy. Some data researchers have criticized its methods and questioned why most of NCRI’s work is not peer reviewed, all while the landscape of social media data research has shifted seismically in the past few years.

How did a neuroscientist studying addiction and mind control in mice turn to researching how hate and misinformation metastasize across the internet? Despite Finkelstein’s relatively recent transition to the field, the connection between the two subjects is clearer than one might expect. For Finkelstein, it all started with puppets.

Finkelstein grew up in Tyler, a city in east Texas of 100,000 known for producing the “Adopt-a-Highway” program, Hall of Fame running back Earl Campbell, and not much else. The son of an Orthodox rabbi, Finkelstein briefly played football for the “Rebels” at his high school, then named for Robert E. Lee, which belied the school’s culture. Finkelstein found more joy in his side hustle — putting on puppet shows for birthday parties, making $100 an event telling stories about superheroes like Spider-Man. “We’d always have characters that should never be interacting,” Finkelstein says. “Mickey Mouse should never be talking to George Washington.”

But if Finkelstein put on fantasies chronicling superhero origin stories, his own life had a way of mirroring the seminal formative moments in such tales. One afternoon, he and his brother got into a fight with a jock. When the bullying turned antisemitic — and the bully and his lackeys started throwing rocks — Finkelstein took cover behind a car. “I remember at that point developing this incredibly strong allergy to antisemitism,” Finkelstein says.

As Finkelstein pursued his dream of becoming a scientist, he soon got involved in a different form of puppetry: studying the inner workings of the human brain.

After undergrad at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a stint at Google, Finkelstein worked with a neuroscientist, James Doty, to start the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education at Stanford University. The research center focuses on understanding the neural origins of compassion and altruism, and there Finkelstein became interested in the field of optogenetics, which examines how neurons can be genetically engineered with light switching to control the brain. He explains that using these processes, scientists can “turn on” anxiety and bonding behaviors. “You can activate all the machinery and get your hands on it,” he says.

For Finkelstein, it was a familiar feeling — just like his childhood hobby. “As soon as I heard about optogenetics, I’m like, ‘Oh, this is it,’” Finkelstein says. “This is the ultimate puppeteering.”

After the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education awarded a grant to Karl Deisseroth, the inventor of the field of optogenetics, Finkelstein took a job in Deisseroth’s Stanford lab and found a new mentor in Deisseroth’s student, neuroscientist Ilana Witten ’02. Then, when Witten joined the faculty of the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, Finkelstein followed her to pursue his Ph.D. in the same field.

At Princeton, Finkelstein’s dissertation involved understanding the neural mechanism to “unlearn bad habits” through an experiment to cause the extinction of a “cocaine memory.” After mice were given cocaine, they formed a preference for the drug. Then Finkelstein studied the mechanisms in mice to erase that memory. By flashing light at neurons in the reward center of the brain, the memory could be weakened, and the addictive spell could be lifted.

As Finkelstein came closer to understanding the secrets of the brain, he stumbled across a startling discovery — just as flashing lights could manipulate the brain, social media could influence it, too.

After Trump’s 2016 election victory, Finkelstein noticed that a lot of his friends and colleagues had become politically polarized. “People who I knew and respected were suddenly speaking with a kind of jargon that became increasingly more political,” Finkelstein says, and he attributed this shift to social media. “A lot of what we do in terms of putting animals in a virtual environment, and then manipulating their brains with lasers, feels a lot like what we do on social media.”

To his dissertation adviser’s chagrin, Finkelstein started spending more time collecting data on extreme speech. “I wasn’t too surprised that he found interests outside of neuroscience,” Witten says. “But of course, I wouldn’t have predicted the exact thing he would find.”

Finkelstein soon discovered that the antisemitic “Great Replacement” theory — that Jews and other minorities are conspiring to displace white people across society — had trended on far-right platforms before the 2017 Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally. He says the spread of the discourse was “mirroring real-world activities,” reminding him of popcorn about to burst from its kettle. He reached out to Craig Timberg at The Washington Post, who published his findings in September 2018.

A month later, a white supremacist named Robert Bowers shot and killed 11 members of the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh. At that point, Finkelstein realized that he needed to be doing this research full time.

In 2018 — with the help of a partnership forged with Sohn after that chance meeting on the plane — the Network Contagion Research Institute was born. Finkelstein explains that the term “network contagion” is often used in the context of financial markets. “It’s where you have bad behaviors or mindless ideas that can freely replicate opportunistically across a gradient because there’s nothing to stop them, and there’s resources to benefit the replication.”

NCRI began to grow in October 2019, when Finkelstein attended a Princeton dinner with John R. Allen, then head of the Brookings Institution and the former commander of NATO forces in Afghanistan. According to Finkelstein, Allen was impressed with his work. He introduced Finkelstein to NYU security analyst Alex Goldenberg and his father, Paul Goldenberg, a former adviser to the Department of Homeland Security and a fellow at the Miller Center on Policing and Community Resilience. Both became key figures in the burgeoning NCRI apparatus.

In the early days, NCRI was operated remotely, with analysts working from home and petabytes of data stored on servers in members’ basements, but it quickly attracted an enthusiastic following. Key to that was the group’s acquisition of Pushshift, an API tool that allowed moderators to search Reddit data. “The research community loved it,” Sohn says. “We had well over 300 universities that had been [making] over 2,000 academic citations using Pushshift data.”

NCRI’s first big break came with its report on the rise of QAnon, which came out three weeks before the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. The report was co-authored by former Virginia Rep. Denver Riggleman, a castoff of the GOP who lost his 2020 reelection bid after officiating a gay wedding. As Riggleman and his co-writer Hunter Walker described in their 2022 memoir, The Breach, NCRI’s initial report “had demonstrated how QAnon’s myths fueled an insular online social group that was increasingly becoming a real-world threat.”

When then Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., brought on Riggleman as a senior technical adviser for the House Select Committee investigating Jan 6., NCRI faced a fork in the road, as the committee was interested in hiring it.

“We realized that we couldn’t do it,” Finkelstein says. Though the committee was bipartisan, Finkelstein says the NCRI team was concerned about the appearance of being involved in a political action, stressing that he views NCRI as apolitical. “Everybody had mixed feelings, because everybody wanted to be part of it,” Finkelstein explains, but ultimately the team agreed that the risk of politicizing the organization was too high. “We really try to make it that the truth is our first client and everybody else is our second.”

“The key problem is that we aren’t paying attention to who we’re becoming, and we don’t feel like we have any control in that. We’ve given that over to the gleam of artificial intelligence and shiny cultural artifacts.”

— Joel Finkelstein *18

Since then, NCRI has taken on a variety of research questions.

In 2023, NCRI’s research pointed to the previously undisclosed influence of Qatari money on university campuses, and the following year, the Chinese Communist Party’s influence, through the Neville Roy Singham network, on the “Shut It Down for Palestine” movement active in the pro-Palestinian protests on campuses after the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel.

In 2024, it also raised the specter of the “Yahoo Boys,” a ring of Nigerian cybercriminals who extort teenagers by posing as attractive women (often using AI imagery), asking for nude photos and then demanding blackmail payment, leading to a string of teen suicides. In January 2024, that NCRI report motivated the Apple app and Google Play stores to remove Wizz, a Tinder-like dating app for teens. Another report, published in November 2024, argued that corporate DEI training pedagogy seemingly stoked racial resentment, rather than improving diversity in the workplace.

NCRI has also worked on behalf of corporate clients. In 2021, it assisted Walmart in efforts to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake in regions where antivaccination views were common.

“It’s not that NCRI is unfocused, it’s that there are risks coming from the cyber-social domain from everywhere,” Sohn says. “There are so many ‘known unknowns,’ and NCRI’s mission is to try to discover them at as fast a cadence as possible and get them into the hands of the people that can do something about it.”

Through the NCRI Labs offered at the Rutgers Miller Center, where Finkelstein has an affiliation, NCRI also aims to train the next generation of internet intelligence analysts, some of whom, Finkelstein says, have gone on to work for institutions such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation. During her time as a Rutgers undergrad, Prasiddha Sudhakar worked for NCRI and co-authored a report on anti-Hindu hate speech on social media, and was later asked by a British government committee to advise its investigation on the subject following a 2022 attack on Hindus in Leicester, England. Today, Sudhakar is a senior analyst and board member at NCRI. “It was only after being really trained by NCRI,” Sudhakar says, “that I learned how to put this together in a formal paper to really understand the scope of how far the hatred had reached.”

Perhaps NCRI’s biggest moment has been its research surrounding TikTok. In December 2023, NCRI released a report arguing that there was a “strong possibility” TikTok was suppressing topics sensitive to the Chinese government, such as hashtags featuring Tibet, Taiwan, and the Uyghur ethnic group, on its platform as compared to Instagram.

Following TikTok’s methodology used in a November 2023 press release responding to accusations of bias in the Israel-Palestinian conflict, which compared the frequency of pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian hashtags on TikTok and Instagram, NCRI analyzed the volume of hashtagged posts of China-sensitive issues on TikTok using the app’s ads manager portal.

NCRI compared the frequency of those posts to those on Instagram using the app’s “explore” feature. For example, NCRI found that posts about Tibet were 37 times more frequent on Instagram than on TikTok, which NCRI argues is evidence of the suppression of the issue by the platform.

Two weeks after the report’s publication, TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, removed the search tools that had facilitated NCRI’s research, making the study impossible to replicate.

During a January 2023 Senate debate over child online safety, Sen. Ted Cruz ’92, R-Texas, invoked NCRI’s research as he questioned ByteDance CEO Shou Zi Chew. “Why is it that on Instagram people can put a #HongKongProtest 174 times compared to TikTok?” Cruz asked Chew, adding, “What censorship is TikTok doing at the request of the Chinese government?”

In April 2024, Congress passed the TikTok ban bill, which forced a U.S. ban of the app or sale to a U.S. company by Jan. 19. After ByteDance’s lawsuit, the Supreme Court upheld the ban, and the app became unavailable for 16 hours, until the newly inaugurated President Trump issued an executive order delaying the ban for 75 days, a ban extended for an additional 75 days in April, and another 90 days in June.

But critics, such as Cato Institute scholar Paul Matzko, have argued that NCRI’s initial report featured flaws in data science that compromised the study, such as comparing Instagram and TikTok across different timespans, as well as the decision to use Instagram as a control variable.

Since Instagram is active in disparate markets and possesses its own distinct algorithm, Matzko argues, the report produced a skewed lens. And if the ban were to be enforced, Matzko says, “there’s the potential for the impairment of the speech of 170 million Americans. And one of the key evidentiary pillars for one of the largest acts of censorship in American history is a report that’s flawed.”

Matzko, who admits to enjoying a large TikTok following of his own, was surprised when his blog post for Cato was cited by TikTok CEO Chew in the same confrontation with Cruz. However, Matzko suggests that for NCRI’s reports to be taken seriously, they need to be peer-reviewed. “They are not academic, even if they can be scholarly,” Matzko says. “You should have a grain of salt when it comes to this work.”

However, in January 2025, a peer-reviewed version of NCRI's follow-up study to their initial TikTok report appeared in Frontiers of Social Psychology.

“One of the things that’s really important to keep in mind about social media, disinformation, [and] censorship-type research is that it’s all happening very quickly,” says Jo Lukito, an assistant professor in communications at the University of Texas, Austin, who argues that a peer-reviewed paper would take years to publish. “It’s fairly common to put together white papers or research reports that are not necessarily peer-reviewed but have a lot more of a timely relevance.”

In the past year, social media platforms have made it harder for researchers to access their data.

In March 2023, under the leadership of Elon Musk, X, formerly Twitter, raised its fees for API access from “free” to packages that start at $42,000 a month, pricing out most researchers. In August 2024, Meta terminated its misinformation tracking tool CrowdTangle and replaced it with the “Meta Content Library,” only accessible to academic researchers, excluding most news organizations.

In 2023, NCRI’s own Pushshift tool was rendered moot by Reddit’s blockade of the tool, an action associated with higher fees for its own platform data.

“The key problem is that we aren’t paying attention to who we’re becoming, and we don’t feel like we have any control in that,” Finkelstein says. “We’ve given that over to the gleam of artificial intelligence and shiny cultural artifacts. That actually isn’t a new problem. It’s a very old one.”

Finkelstein likens the rise and disruptive spread of social media to the media revolution that accompanied the arrival of the Gutenberg printing press in early modern Europe. Before the printing press, he argues, media was spread by monks to a population that was illiterate. But when the press came along, suddenly there was a lot more media, and many more people who were literate to ingest it. The first “bestsellers” in modern Europe, Finkelstein says, were the Gutenberg Bible, yes, but also the Malleus Maleficarum, a witch-hunting guide, and Martin Luther’s 1543 antisemitic treatise, On the Jews and Their Lies.

“The network, which is used to a certain bandwidth, is now being saturated and breaking at the seams,” Finkelstein says, arguing that the revolution that follows brings with it distrust in institutions and a response by authoritarian regimes to restore order (often by blaming witches and Jews). “Once you decide all these people are monsters,” he adds, “there’s no reaching out to them.”

To make the comparison concrete, Finkelstein has directed NCRI to study how social media users appear to be more willing to violate civil norms and see people with opposing viewpoints as the enemy. In December 2024, NCRI released a report stating that 78% of the users of Bluesky, a mostly progressive alternative to X, considered that Mangione’s assassination of Thompson, the United Healthcare CEO, was justified, and “only extremist platforms such as Gab or 4chan evidenced similar levels of endorsement for the murder.”

Finkelstein attributes much of his thinking on institutions and the health of American society to conversations held with Princeton politics professor Robert P. George, who is listed on NCRI’s website as a “strategic adviser” and authored an introduction to the group’s 2020 paper on antisemitism. In an email to PAW, George downplayed his involvement with Finkelstein and said he does not take an active role in NCRI’s operations.

In describing NCRI’s role going forward, Finkelstein says the group is not supposed to be like the precrime investigators in the 2002 science-fiction film Minority Report, in which a policeman played by Tom Cruise, privy to the oracular visions of psychics, arrests people who will commit murder in the future. Rather, to Finkelstein, NCRI is a cross between “an intelligence agency and a public trust” — and in a more colloquial reference to Harry Potter, “Defense Against the Dark Arts.”

These investigations cost money, and in the past, NCRI relied on contributions from Rutgers University and philanthropist David Magerman, as well as several anonymous donors. At the end of 2024, Sohn stepped down as NCRI CEO to lead the organization’s partner venture, Narravance, a for-profit research intelligence firm that has launched an investment tool called “ChatterFlow,” which charts the risk landscape of the stock market in real time.

Sohn says that establishing Narravance was critical to keeping NCRI independent, as Narravance supports NCRI through shared resources and intellectual property. And because Narravance can hire talent at competitive salaries, these staff can also consult on NCRI projects.

“It’s a wonderful story of being able to keep the mission of a nonprofit alive without having to rely on the gratuitous nature of just a few high-net-worth individuals,” Sohn says, allowing “the private market [to] give [NCRI] a fighting chance.”

That system has already led to new partnerships for NCRI. In May, NCRI announced a collaboration with the Ed Snider Center for Enterprise and Markets, part of the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business. The new lab — facilitated by a financial donation from Narravance and access to its ChatterFlow tool — will analyze how social media can influence markets and trading behaviors.

For Finkelstein, who believes he can tease out the strings attempting to “puppeteer” the American public, there’s a lot of work ahead, particularly in a second Trump administration that has spurred greater polarization.

“The greatest lie that’s been told in the age of technology is the obsolescence of human beings,” Finkelstein says. “We’ve never been more important.”

Harrison Blackman ’17 is a freelance journalist and writer based in Los Angeles.

1 Response

Van Wallach ’80

6 Months AgoTyler’s Pride in Horticulture

The article on Joel Finkelstein *18 was balanced enough, but its description of Tyler, Texas, was way lacking. By snidely mentioning that Tyler is “known for producing the ‘Adopt-a-Highway’ program, Hall of Fame running back Earl Campbell, and not much else,” the author omits any mention of Tyler as “the Rose Capital of America.” Having visited family members in Tyler numerous times, I know the place takes pride in its horticulture. “And not much else” is the kind of pointless dig at Flyover Country that makes PAW such a perverse joy to read these days.