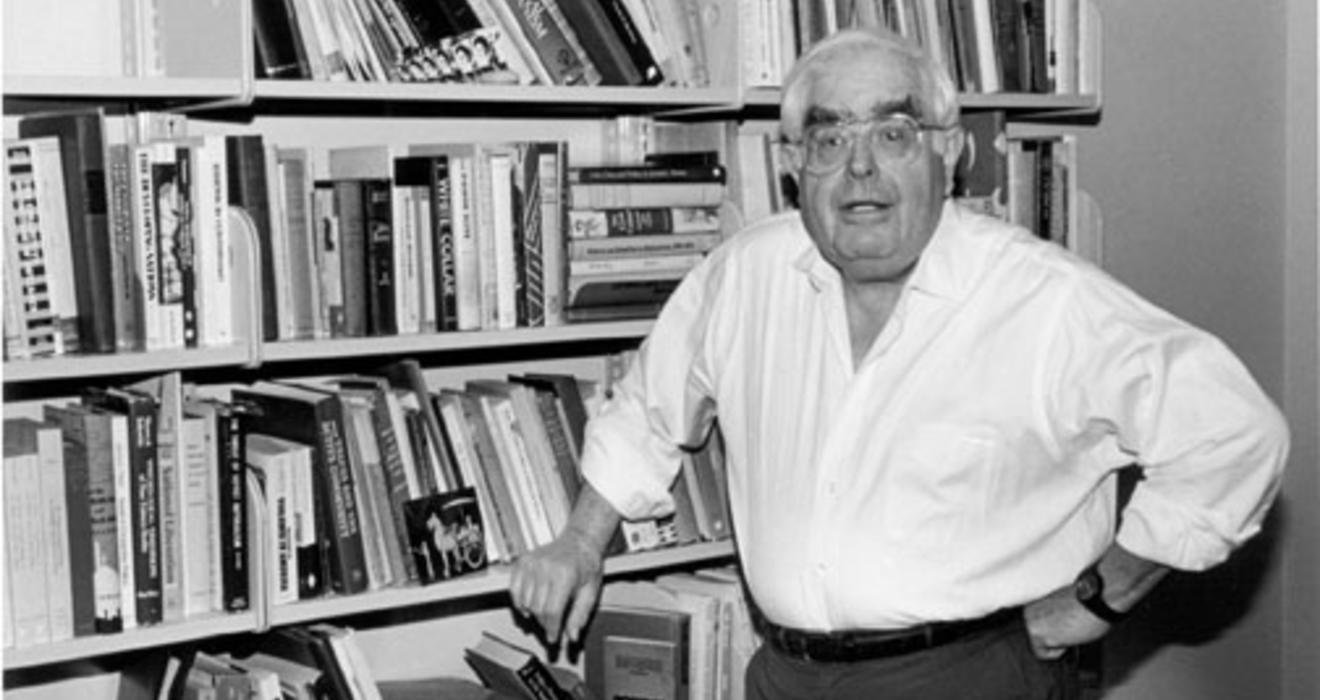

The subtitle to the introduction of Manfred Halpern’s posthumously published magnum opus, “Transforming the Personal, Political, Historical and Sacred in Theory and Practice,” is “Invitation to an Unfamiliar Journey.” That describes not only the journey Halpern believed all people take in life, but the journey his book took on its road to publication. Halpern, a longtime professor of politics at Princeton, died in 2001. It was not until eight years later that the manuscript he labored over for much of the second half of his career reached completion, thanks to his colleague and former student, David Abalos.

It was an unusual collaboration, one that began long before Halpern, knowing that he had only weeks to live, asked Abalos to take the manuscript home and finish it. For more than a decade, Halpern would share chapter drafts, scratched in pencil on yellow legal pads, which he and Abalos would pore over before Halpern finally sent them to a typist.

“We just had the most wonderful conversations about it,” Abalos recalls.

Even so, the manuscript Abalos inherited was in several computer file formats, lacked source attributions and footnotes, and had no final chapter. Filling those holes took years as well as time away from Abalos’ own work as a professor at Seton Hall University and as a visiting professor at Princeton. Yet he has insisted that Halpern get sole credit as the author of the book, which was published in the fall by the University of Scranton Press. Abalos lists himself as editor.

“People say congratulations, but I say this was Manfred’s book,” Abalos says. “I just feel happy that I was able to bring it to publication.”

Halpern’s theory, which Abalos says is applicable to all human experience, was born of his study of the Middle East and the difficulty that the region and traditional societies face in adapting to a changing world.

Life, Halpern argued, is a journey in which the “four faces of our being” — the personal, political, historical, and sacred — are transformed. That process occurs, like a stage drama, in three acts. Act I he called emanation, a way of life lived in the service of a dying set of loyalties and customs. As the old certitudes, whether they be Islamic fundamentalism, socialism, or capitalism, fail to enable humans to achieve their fullest existence, life moves into Act II, which Halpern called incoherence, a stage in which people and societies struggle to re-create life from fragments of the old way of doing things. In many cases, Act III begins with what Halpern called deformation, when attachment to a single fragment of life leads to violent outbursts, such as terrorism, xenophobia, racism, or other forms of repression. If we persevere, however, Halpern said that we ultimately reach transformation, a state in which all four faces of being are liberated and people can be truly themselves.

“We live at every moment ... in the core drama of transformation, and nowhere else,” Halpern wrote. “But if we arrest ourselves at a crucial moment in this process of renewal and consolidate it into a way of life, then, living within a fragment of the core drama of life, we cannot solve any fundamental problems.”

Halpern was born in Weimar Germany, in 1924, into just the sort of disintegrating society that he later would try to understand. He was raised amid secular socialism, but in 1937 he and his parents, both nonobservant Jews, fled Nazi persecution and moved to the United States. After serving in the infantry during World War II and fighting in the Battle of the Bulge, Halpern joined the counterintelligence service at the war’s end, tracking down Nazi fugitives.

Like many veterans, Halpern returned to college, earning a B.A. in literature with highest honors from UCLA in 1947, and eventually a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins. In between, he worked for the State Department as director of research for Europe; senior analyst in the division of the Near East, South Asia, and Africa; and in other posts, receiving the department’s meritorious-service award in 1952. By the time he arrived at Princeton as a visiting associate professor in 1958, he already was at work on his first book, The Politics of Social Change in the Middle East and North Africa. The book is considered a classic in its field and has had six printings.

Although Halpern continued to teach at Princeton until his retirement in 1994, producing more than 30 scholarly articles and book chapters, he did not publish another book. He had grown disenchanted because traditional political models, he felt, did not explain adequately the process of transformation that he saw occurring in traditional societies. Over a period of decades, Halpern explored and developed his own theories in numerous articles and in two Princeton courses, “The Sacred and the Political” and “Political and Personal Transformation,” both of which were so much the fruit of his own ideas that the University ceased to offer them after he retired.

Emeritus professor Fred Greenstein, a longtime colleague, characterizes the new book as “a work of true dedication, for which he forswore a career as a well-recognized Middle East specialist.” If Halpern did not receive the recognition that his achievements might have warranted, Greenstein says, his peers appreciated their importance. “One of my colleagues,” he says, “had the nightmare that he was reading a history book of the future which described him as a minor contemporary of Manfred Halpern.”

Halpern also was recognized as an outstanding teacher, whose courses Princeton undergraduates twice listed among their 10 most popular. He would begin each semester by insisting that students think for themselves, saying, “Don’t believe what I say. Test it with your own life, with your own experience.” One of his first students in the late 1960s as he was beginning to develop these new theories was Abalos, who was pursuing his Ph.D. at Princeton Theological Seminary and taking classes at Princeton. Halpern always was concerned, Abalos recalls, that his work should not become so philosophical and abstract that it would be unintelligible. Over the course of many years, Abalos helped Halpern test his theories by applying them to Latino politics, particularly in two of Abalos’ books, Latinos in the United States, The Sacred and the Political and The Latino Family and the Politics of Transformation.

Halpern seems to have known that he was running out of time in which to complete his book. Two bouts with cancer, the first in the 1980s, had been pushed into remission, but in 2000 a CAT scan showed that the cancer had returned and metastasized to his brain. Given three weeks to live, Halpern turned again to his former student. “David,” Halpern said, “take this manuscript home and finish it.” Just days later, on Jan. 14, 2001, Halpern died at home. His wife, Cindy, told The Daily Princetonian shortly after his death that her husband was “pure soul,” and a radical to the end.

It was not until Abalos began to work on the book that he realized what a large undertaking it was going to be. For one thing, there was no complete manuscript, but rather pieces and chapters on different disks and in different formats. A graduate assistant, Christopher Mackie *06, managed to pull everything into a single file so that Abalos could begin the process of revising and editing.

Though Halpern had completed all but the final two chapters, even the finished chapters required the filling in of some details. Chapter 15 — called “What Kind of Theory Is This?” — was written in longhand and the numerous quotations contained no sources or footnotes, all of which Abalos had to hunt down. “Thank God for the Internet,” he says.

Abalos had even less to go on to prepare the final chapter, “On Justice.” Before tackling it, Abalos pored through a large folder containing miscellaneous handwritten notes and ideas, in order to synthesize Halpern’s thoughts. In a stroke of luck, he also stumbled upon an early draft of the chapter, and this gave him a rough framework upon which to incorporate Halpern’s later thinking and complete the chapter.

In one of their last meetings, Halpern exhorted Abalos, “Don’t be a scribe. Let your own voice be heard. If you disagree or don’t understand something, put an asterisk there and say why you don’t agree.” That did not prove necessary, Abalos says, nor was it difficult to write in Halpern’s voice. “We had spent so much time talking about this,” he says. “And we complemented each other very well.”

Halpern had submitted a very early version of the book to the Princeton University Press, but withdrew it because there was much more he wanted to say. “Above all,” Abalos explains in the book’s preface, “he felt that he had not written enough about the deepest realm of our lives, the source of the fundamentally more loving and just, the deepest sacred source that inspires us to participate in the continuous journey of transforming the personal, political, historical, and sacred faces of our being.” Abalos sent the completed manuscript to 10 other publishers before the University of Scranton Press accepted it.

The book was published in November. Its journey, and Halpern’s, were complete.

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

No responses yet