A Language for Idealists

Professor Esther Schor takes a new look at Esperanto, invented to unite the world

THE SWEET-FACED TODDLER GAZES expectantly at the camera. “Kie estas via nazo?” asks an off-screen adult voice. “Nazo,” the little boy repeats, planting a pudgy index finger on the side of his nose.

It’s just another cute-baby video from YouTube, except that this one shows something remarkable: an American child on his way to becoming a native speaker of Esperanto, a language invented 130 years ago by a Polish Jewish eye doctor on an idealistic mission to repair a broken world.

Alternately embraced and mocked, persecuted and ignored, Esperanto has stubbornly survived, and today it is spoken by an international community whose members are estimated to number anywhere from the tens of thousands to 2 million. Esperantists open their homes to Esperanto-speaking travelers and mingle at conventions where they wear the Esperanto color (green), sing the Esperanto anthem (“La Espero” — “The Hope”), buy Esperanto sex manuals and Shakespeare translations, and share the foods and cultures of their native lands. And a few of them raise denaskuloj (“from-birth-ers”) — Esperanto-speaking children or grandchildren.

“You’re in a room, and there’s someone from Nepal and someone from Cuba and someone from China and someone from Japan and someone from Indonesia, and they’re all speaking Esperanto and drinking mojitos,” says Princeton English professor Esther Schor, whose history-cum-memoir, Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language, was published last fall. “It’s just kind of an amazing feeling.”

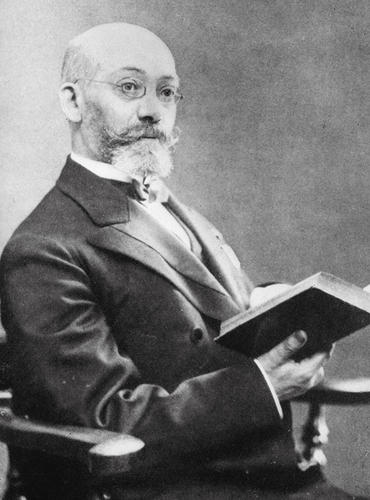

Esperanto was the brainchild of Ludovik Lazarus Zamenhof (1859–1917), who was born in the multilingual city of Bialystok, in Russian-controlled Poland, where Jews, Poles, Germans, and Russians lived in mutual hostility. From his teenage years, the linguistically gifted Zamenhof dreamed of inventing a new language that would bridge ethnic and national differences — not by replacing native languages, but by becoming a universally shared second language for people around the world.

The project wasn’t as quixotic as it sounds, says Princeton history professor Michael D. Gordin, whose 2015 book Scientific Babel examines how English displaced predecessors like Latin, French, German, and Russian to become the primary language of scientific publication. At the time Zamenhof was developing his ideas, scientists were beginning to worry that important discoveries might be overlooked if researchers couldn’t understand the languages in which they were published. A neutral “constructed language,” which would short-circuit European nations’ jockeying for linguistic predominance, seemed like a viable solution.

“It wasn’t a bunch of weirdos,” Gordin says. “It was always a marginal movement, but it was a serious movement that serious people took seriously. It was grava, as Esperantists would say.”

In 1887, Zamenhof — by then a trained ophthalmologist who would eventually practice among the impoverished Jewish citizens of Warsaw — unveiled his new language in a pamphlet published in Russian under the pseudonym “Doktoro Esperanto” (“Doctor Hopeful”). The founding document, which Esperantists call the Unua Libro (First Book), laid out 16 fundamental principles and listed 900 prefixes, suffixes, and word-roots, but it left most of the work of vocabulary-building up to the language’s users.

To make his new language easy to master, Zamenhof eliminated the irregular verbs and arbitrarily gendered nouns that bedevil language learners. Esperanto’s roots are drawn from German, English, Russian, and especially the Romance languages; most of its conjunctions and particles come from Latin and Greek. Every singular noun ends in “o,” every plural noun ends in “oj” (pronounced like the English “oy”), every adjective ends in “a,” and every adverb ends in “e.” Many common adjectives like bona (good) can be transformed into their opposites by adding the prefix mal- (malbona = bad), halving the vocabulary that learners must memorize. New words are coined by stringing together roots and affixes.

Spoken Esperanto sounds a bit like a Slavic-sprinkled Italian, and with no ethnic or national community to insist on a received pronunciation, every speaker invests the language with an individual accent derived from her own native tongue. Written Esperanto looks semifamiliar to an English speaker, even one with no prior knowledge of the language.

When Luke Massa ’13, a Princeton philosophy major who now works as a software engineer, wanted a secret language he could speak with a friend at his suburban Philadelphia high school, Esperanto seemed the perfect choice. After four months of online study and conversation, the two friends were more proficient in Esperanto than in the German they had studied for years in school, Massa says.

As a vehicle for covert hallway gossip, however, Esperanto fell flat. “It really sort of failed as a secret language, because there are so many words in it that are cognates to English or French,” Massa says. “People could figure it out.”

Living amid the interethnic tensions of turn-of-the-20th-century Eastern Europe, Zamenhof had loftier goals for his project, which soon came to be known by his pseudonym. “He dreamed of a language as a tool for building something that he didn’t have,” says Carolyn Biltoft *10, a Princeton history Ph.D. whose forthcoming book on the interwar League of Nations includes a chapter on the language-reform and language-creation movements. “He thought that language might be a tool for achieving a transborder conception of a peaceful community.”

In the decades after the publication of the Unua Libro, Esperanto gained adherents and suffered growing pains. Zamenhof’s Jewishness repelled some early Esperantists, especially after he codified his universalist vision into a religious philosophy, eventually called Homaranismo (“Humanity-ism”), based on the ethical teachings of the Jewish sage Hillel. In 1907, Esperanto faced its most significant challenge when a conference that had convened to select an international auxiliary language from among some two dozen competitors passed over the leading contender, Zamenhof’s Esperanto, in favor of a reformed Esperanto known as Ido. In the resulting uproar, perhaps a quarter of Esperanto’s leaders, but a far smaller percentage of rank-and-file users, defected to the new language, which fizzled out in less than a decade.

As European nationalism devolved into world war and revolution, Esperanto’s utopianism frequently inspired hostility, Schor’s book shows. (An Esperanto history of the movement, forthcoming in English, is titled Dangerous Language.) Esperantists — who, as Gordin points out, were often involved in other forms of social or political activism, from vegetarianism to pacifism — were persecuted by Stalin and by the Nazis; all three of Zamenhof’s adult children died in the Holocaust. Efforts to make Esperanto one of the official languages of the League of Nations foundered. During a 1922 debate, a Brazilian delegate called Esperanto a language of “ne’er-do-wells and communists.”

At a moment when governments were deploying language as a tool of propaganda and warfare, Esperanto aimed “to undermine the power structures embedded in language,” says Biltoft, an assistant professor of international history at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva. “It was moving against the grain of power sources that were increasingly using communication technologies and standardizing languages in violent ways, to consolidate power.”

In post-World War II Eastern Europe, embracing Esperanto provided a way for dissidents to forge links to the West, via Esperantists and their organizations, and to express “quiet resistance” to their regimes, Schor says. But Gordin notes that some communist regimes actively promoted Esperanto as well, seeing it as a way for their people to communicate with others in the Eastern bloc. Esperantists like to portray themselves as embattled dissidents, “because it gives a sort of heroism to the story,” he says. “And there’s plenty of heroism without having to make up reasons.”

Whatever the European situation, at least one Cold War institution assuredly associated Esperanto with communism: the U.S. Army, which used Esperanto as the language of a fictional enemy known as “Aggressor” in a training exercise employed from 1947 to 1967. “Onto Zamenhof’s language of peace, equality, and world harmony, the Army projected its terror of — and disgust for — communist aggression,” Schor writes. (Ironically, during the same period, the American Esperanto movement was tearing itself apart in a McCarthyite effort to unmask supposed communist infiltrators.)

Although Esperantists like to think of themselves as politically neutral, the language’s countercultural thrust is inherently political, Schor argues. Esperanto “symbolized an alternative to the given, and certainly an alternative to totalitarianism, an alternative to repression and bigotry and to war,” she says. “It’s not partisan, but I think it’s deeply embedded in the political nature of human beings.”

In its oppositional nature, Esperanto differs radically from English, which today serves as a de facto international language, performing some of the functions that Zamenhof once envisioned for Esperanto. English, which spread around the globe via the imperial might of Britain and the economic muscle of the United States, is far from the peaceful, neutral tool that Zamenhof imagined, Schor says.

“There’s a power story behind it, and this is what Esperanto eschews,” Schor says. “Esperanto is not a language that’s promoted by power. It’s a language promoted by conviction, by love, by idealism.”

As a high school student in India, Avaneesh Narla ’17 was attracted to Esperanto in part because of his annoyance at the postcolonial persistence of the language of British colonialists. “I hated the fact that everybody was learning English,” says Narla, a physics major who speaks six languages but says he is no longer proficient in Esperanto, his seventh. “Why can’t we just learn Esperanto? I liked the idea a lot.”

In an English-centered world, native speakers have an edge over those who acquire English later — an inherent unfairness that bothers Alice Frederick ’17, an anthropology major from Texas who is writing her senior thesis on the contemporary Esperantist community. “What I like about Esperanto is that it really removes my privilege as a native English speaker,” says Frederick, who learned the language in order to attend international Esperanto conferences and consult the archives of the Netherlands-based Universal Esperanto Association. “It was like the tables were suddenly turned on me. I was obligated to learn this language if I wanted an ‘in’ in the community, and I’d never had that experience before.”

The fact that virtually all Esperanto speakers start out as fledgling second-language learners — native-speaking denaskuloj remain a small minority, numbering perhaps 1,000 people, Gordin estimates — has helped forge Esperantists into a friendly, welcoming community. For decades, Esperantists have maintained the Pasporta Servo (Passport Service), a listing of Esperanto speakers around the world who are willing to host fellow Esperantists for a night or two. Massa, the 2013 Princeton graduate, has never used the service, but when he travels, he wears his Esperanto lapel pin — a green five-pointed star — to announce himself to any fellow Esperantist he might encounter (no luck so far). “It’s something for me, to remind myself about what I think about languages and travel and the world,” Massa says.

Schor joined the Esperanto community in 2007–08, not long after publishing a biography of the 19th-century American Jewish poet Emma Lazarus. As she cast around for a new project, she considered “other Jews who were thinking outside the box” and remembered hearing of Zamenhof.

In the course of her research, Schor took a three-week Esperanto immersion course in San Diego; attended Esperanto conferences in Turkey, Vietnam, Cuba, and Poland; browsed through an illustrated Hungarian-Esperanto sex guide; visited a school and foster home run by Esperantists in rural Brazil; and spent a chatty day in Uzbekistan with the Esperanto-speaking director of Samarkand’s International Museum of Peace and Solidarity.

“Zamenhof’s real insight, I think, is not the language itself, but it’s that you can’t have a language without a community of speakers,” says Gordin, the Princeton history professor. “Building the language, he also built the community of speakers.”

And of readers: Zamenhof himself translated Hamlet and the Hebrew Bible into Esperanto, and today it’s possible to read Esperanto-language versions of everything from Dante’s Inferno to Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, as well as original works of prose and poetry. Schor, herself a published poet, tried translating Elizabeth Bishop into Esperanto (verdict: not easy).

Online, today’s would-be Esperantists can study for free through the website lernu! (www.lernu.net), which reports 200,000 registered users, or with the help of the language-learning app Duolingo, which claims 569,000 students of Esperanto. Esperantists can look up information on Vikipedio, meet in online forums to debate the most appropriate Esperanto coinage for terms like “smartphone” and “flash drive,” or visit YouTube to watch clips of Esperanto rock bands and a full-length (albeit subtitled) version of one of the world’s few all-Esperanto movies, the 1966 horror film Inkubo (Incubus), starring a pre-Star Trek William Shatner.

Despite this flourishing culture, however, Esperanto has always encountered plenty of dismissiveness and ridicule. In 1908, Theodore W. Hunt, the first chairman of Princeton’s English department, told a gathering of the Modern Language Association that constructed languages like Esperanto “can never rise to the plane of language as the expression of thought for the highest ends.” (At least one of his Princeton colleagues disagreed: Some years earlier, retired biology professor George Macloskie had translated the Gospel of Matthew into Esperanto.) A century later, late-night TV host Stephen Colbert attended the 2014 Comic-Con costumed as Prince Hawkcat, supposedly the star of “the most popular human-animal fantasy hybrid franchise ever published” — wait for it — “in Esperanto.”

Earlier this year, Frederick, the senior anthropology major, found herself bristling unexpectedly when a professor jokingly compared Esperanto to Klingon, the language of the extraterrestrial villains on Star Trek — a language invented to serve the purposes of commercial entertainment, not utopian idealism. “I immediately wanted to jump in,” Frederick says. “I kept my mouth shut, but it struck me as something that Esperantists might call an indignity.”

From time to time, Massa was forced to defend Esperanto from the criticism or mockery of fellow students who passed by the poorly attended mealtime Esperanto table he founded in Rockefeller College. Esperanto is “the thing I’m the most irrational about in my life,” Massa says. “I will defend it forever, and I know that, and I am ready to do that at the drop of a hat.”

Esperanto attracts scorn in part because of the very nature of the project. “There’s a silly notion that because it’s an invented language, it can’t be a real one,” says David Bellos, a professor in Princeton’s comparative literature and French and Italian departments, who arranged daily Esperanto lessons for the Princeton students he taught during a six-week-long global seminar on multilingualism, held in Geneva, in the summer of 2014. “If you stop to think about it, most languages have been invented at some point. When they were invented isn’t really relevant to whether or not they can be made to serve the functions that you want a language to serve.”

Esperanto’s earnest idealism also exposes it to attacks from the more cynical. Zamenhof wholeheartedly embraced the notion of an interna ideo (inner idea), a higher purpose to which his new language was dedicated, and even today, Esperantists call each other samideanoj: “same-idea-ers.”

Exactly what that inner idea consists of seems up for grabs, however. Over the years, suggestions from scholars, movement leaders, and ordinary Esperantists have included not only Zamenhof’s Homaranismo but also peace, social justice, language justice, interethnic harmony, anti-nationalism, and anti-fascism. Nor is it obvious that Esperantists must embrace any interna ideo at all. “It is possible to approach Esperanto and to make use of Esperanto without feeling that you have to be a vegan, long-haired, sandal-wearing peacenik,” says Bellos. “It’s about how you can ease the difficulties of the world by having a common interlanguage.”

Narla, who has taught Esperanto mini-classes to local high school students and to fellow Princeton students during Wintersession, believes Esperanto’s future may lie in its usefulness as a tool for promoting second-language acquisition. In Britain, a small program called Springboard to Languages claims that school-age children who first master Esperanto’s transparent, regular grammar gain the confidence and structural grounding they need to tackle more complicated languages — just as learning the recorder prepares music students to play more complicated instruments. “French in the classroom is a bassoon,” Springboard’s creator, Tim Morley, argues in a 2012 TEDx talk. “Esperanto is a recorder.”

Such modest goals seem a far cry from Zamenhof’s vision of the finavenko (final victory) — an Esperanto-speaking world. These days, his ambition seems more distant than ever, and realizing it, were it possible, might not even be desirable, suggests Frederick, the senior anthropology major. “Esperanto is kind of in a bind in this way,” she says. “It wants to be the second language for the world, but in order to do that, it would ultimately have to become so huge that people felt this sense of obligation to learn it, like if they didn’t, they would be missing out. Esperanto would become invested with this power that it has really avoided trying to have. It can aspire to be like English, but I almost think it would lose some piece of itself if it did that.”

In any case, Schor says, Esperantists no longer believe in that aspect of Zamenhof’s dream. “Finavenkismo is finished, is over,” she says. “No one thinks it’s going to happen.”

Not so fast, says Bellos, her Princeton colleague. Nowadays, English is firmly entrenched as the international language, he says, but once upon a time, so were Sumerian, Ancient Greek, Latin, and French.

“Over the course of human history, no central language has ever stayed central for more than a few centuries,” Bellos says. “Something will change one day. Esperanto is a perfectly reasonable project, and people may come to it. I think it’s utterly premature to say that it’s missed the boat.”

Deborah Yaffe is a freelance writer based in Princeton Junction, N.J. Her most recent book is Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom.

VIDEO: Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language, by Esther Schor

Courtesy Henry Holt

6 Responses

Miko Sloper

8 Years AgoIt cannot be claimed that...

It cannot be claimed that Esperanto does these tasks better than other languages; this well-engineered language functions just as well as any other. Its main advantage is that it is easily learnt, and it is also important that it is politically neutral.

Matt Conner ’88

9 Years AgoAn interesting article, but...

An interesting article, but despite its title about ideas, this one stopped on the threshold of some important ones. It would appear that Esperanto is an efficient language, easily learned, that can resist the “power structures” represented by more established languages like English. That’s fine, but is a language any more than a power structure? Chinese has recorded the thoughts and feelings of one of the world’s major civilizations for thousands of years. There is a body of work about how the hybridization of Ango-Saxon, French, and Latin adapted English for developing an ethic of personal freedom that it spread. To consider another representative medium, blues music, which grew out of the tragedy of slavery, has a pathos that is more than a theoretical description of its chords. The role of language has been theorized in a great variety of ways that include mirror, lamp, communication tool, aesthetic object, speech-act, reservoir of the unconscious, ideological register, archive, philosophical game and much more. To propose that an invented language could do all this better than the ones that have developed over history seems improbable.

Angelos Tsirimokos ’74

9 Years AgoI am tempted to copy...

I am tempted to copy Dietrich Weidmann’s comment word for word.

As a Princeton undergraduate in the 1970s, I met precisely one other Esperantist among the students. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, he was of recent European origin and settled in Europe later.) It is good to hear that a professor is now sympathetically exploring this rather peculiar phenomenon ...

Dietrich Michael Weidmann

9 Years AgoCongratulation for your very...

Congratulation for your very interestic article about my beloved Esperanto...

David MacLeod

9 Years AgoNo idea where you got the...

No idea where you got the idea that Ido “fizzled out in less than a decade.” I’ve spoken it for hours at a time with various people and it is very much alive. Small (about 1000 users total), but alive.

Don Cantrell ’53

9 Years AgoLinguistics and Language

Dankon pro via engaĝi artikolo pri Esperanto! Kiel studento de la hispana dum miaj studentaj kariero, kaj fine kiel instruisto de hispano en miaj postaj jaroj, Esperanto estis de iu intereso por mi, sed mi neniam eniris gxin. Via artikolo vekis interesoj kiuj bezonas multe pli studo!

(Translation: Thank you for your engaging article about Esperanto! As a student of Spanish during my undergraduate career, and finally as a teacher of Spanish in my later years, Esperanto has been of some interest to me, but I never went into it. Your article aroused interests that need much more study!)