Sideshow Bob: “Oh, come now! You wanted to be Krusty’s sidekick since you were 5! What about the buffoon lessons? The four years at Clown College?”

Cecil: “I’ll thank you not to refer to Princeton that way!”

“Brother from Another Series,” The Simpsons, Season 8, Episode 16

When a Princeton Alumni Weekly editor called and asked if I wanted to write a story on the funniest Princeton professors, I immediately and enthusiastically accepted. Though writing an article on funny Princeton professors certainly would cut into the time I had set aside for my book on the NBA’s greatest Jewish slam-dunk champions and my end-of-the-year countdown of 2010’s most popular investment-bank CEOs, the PAW idea inspired me instantly, tickling me in all of the right creative anatomical crannies. Who knew what closet Seinfelds or Sandlers toiled undiscovered at Old Nassau? Despite not yet having heard one professorial joke, I imagined that the article might spawn a reality show, an anthropological exposé of a heretofore unknown segment of society — The Real Gauss Lives of New Jersey, Are You Funnier than a B+ Grader, Last Academic Standing. As for the article itself, the content would be so surprising that I would not be surprised if this became the first Princeton Alumni Weekly to be sold at the front of super market checkout counters, as the finished cover page appeared instantly and clearly in my mind:

Paul Krugman on airline food!!!

Sir Andrew Wiles on the kind of people who watch Antiques Roadshow!!!

And don’t miss Toni Morrison’s unforgettable 267-page version of “The Aristocrats”!!!

Yes, Virginia: PRINCETON PROFESSORS ARE FUNNY!

There seemed to be, however, just one hitch. As English professor Jeff Nunokawa so eloquently stated: “We’re all academics here. We’re not funny.”

Of course, the possibility of a total absence of even mildly humorous professors had occurred to me. Distant though it seems, I once was a Princeton undergraduate who did not, I confess, find my professors particularly gut-busting. I can say with confidence that when the Undergraduate Student Government holds comedy nights, there is a reason it hires professional stand-up comedians rather than, say, the linguistics department. None of my classes ever was canceled mid-semester because the professor had scored an eight-episode arc on 30 Rock.

And yet I could not give up, or let the assignment fall to another writer, for I had a horse in the race; and that horse was me. A few months earlier, I had ended my one year as a professor, teaching intermediate English courses at a university in Thailand. And I realized with some horror that if my Thai students who knew me only from my lectures — especially my Monday 8 a.m. lectures — were to describe me, “funny” would not have made their list of descriptors. “Monotonous,” yes; “sepulchral,” sure; “a Herzogian nightmare,” in some cases — but not, I fear, “funny.” Part of me wanted to investigate and elucidate the subject matter as a defense, an apology, a pre-emptive retort to a playground insult that remained unslung.

And so I ask you to think back, Princeton alumni, to imagine the lecture hall you most often frequented, your home department’s home base — the creaky, smoothed-wood writing desks of McCosh, the sterile conference-room tabletops of the Robertson Hall bowls — and remember this, if you can: that when you sat in class crusty-eyed on a Monday morning or heavy-lidded on a Thursday afternoon, your favorite professor, in the middle of a heartfelt and profound exploration into an integral part of the curriculum, broke tone for an instant and cracked a joke, from out of nowhere, and, like a middle-of-the-night fire alarm that wakes an entire building of sleeping tenants, you and your classmates laughed — relieved, surprised, exhaling as one.

It seemed to me that this generic scene occurred each semester, in each class, of each year of my four at Princeton. And so I headed back to campus in search of Princeton’s funniest professor.

If a notebook-toting, dandruff-bearded young PAW reporter, unkempt as a lumberjack, zigzagged toward me on McCosh Walk and asked, without introduction, for a list of my funniest Princeton professors, I would not have begged off and claimed I was late for a nonexistent lecture or hair appointment; but rather, I would have replied with confidence:

“Mr. Reporter, Sir, my answer is simple. Every English major should be so lucky to bookend their surveys of the canon with:

“On the one side, D. Vance Smith’s Middle English interpretation of the 1985 Dead or Alive dance-hit single ‘You Spin Me Round (Like A Record),’ whose chorus, as rendered by the Pearl Poet, is: ‘Yow speen may richt roond richt roond bahbeh richt roond’; and on the other end, Benjamin Widiss’ line-by-line reading of ‘Kyle’s Mom,’ an impossibly profane song from the impossibly profane 1998 cartoon movie South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut, as a subversive and uncompromising feminist salvo against the double standard that the media and Hollywood set for strong woman leaders.

“These — with Sophie Gee, Michael Cadden, and Lawrence Danson — are the linchpins of a humorous Princetonian English education. Thank you, Good Reporter Sir, and best of luck on your quest.”

I admittedly had thought longer and harder about the subject than my interviewees. Indeed, after my first morning of randomly asking undergraduates the question, “Have you ever had any funny professors at Princeton?” a very clear non-English department favorite had emerged:

Capturing nearly 100 percent of the vote, Professor Uh-No of the Japanese department, congratulations — you are the funniest professor at Princeton University!

(For those of you wondering about Professor Uh-No, I give you the answer that I most often received to the question “Have you ever had any funny professors at Princeton?”: Uh, no.)

To the more direct question “Who is the funniest professor you have ever had?” I received an answer that either was a reassurance that the Socratic method still is in use at Princeton or proof that Goodfellas had just been screened by the University Film Organization, as an entire campus squinted, smirked, and wondered aloud: “What do you mean by funny?”

Apparently, many students find their professors to be unintentionally funny, but for the purposes of this competition, intent does matter. Also ruled out: professors who wear humorously mismatched clothes or irregularly large eyeglasses; professors who sound like Borat or Philip Seymour Hoffman when they speak; and professors whose foreign names, when transliterated into English, resemble curse words or euphemisms for the male anatomy.

“Michael Wood is pretty funny,” one student told me of the highly regarded (and quite witty) English professor, breaking a long string of non-answers and absent headshakes.

I was thrilled.

“What makes him so funny?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” the student said. And then, after a moment’s thought: “He kind of looks like Michael Caine.”

This did not qualify a professor, either.

Most students were more eager to tell me which professors and departments were not funny, rather than which ones were (“I don’t have any funny professors,” a sophomore in front of Brown Hall told me. “He’s an engineer,” his girlfriend apologized). And many professors recommended to me were, in the grand postmodern tradition, inevitably unreachable. An entire faculty’s worth of funny professors seemed to be suspiciously missing during the semester of my investigation — on sabbatical, on international exchange, not lecturing, writing a book, on maternity leave, semi-retired.

“Oh, I have the perfect person for you!” computer science professor Bernard Chazelle cried with his slight French accent. “Except, he is dead.”

Other professors were less forthcoming in their praise, for the dead or the living. During a lengthy stop at the astrophysics department, I told Professor David Spergel ’82 that I was surprised by how funny some math professors were when I had talked to them. Professor Spergel scoffed jovially and offered an appraisal of his neighbors in Fine Hall:

“How do you tell the difference between an introverted math professor and an extroverted professor?” he asked me.

“I don’t know,” I said eagerly, notebook in hand. “How?”

“An extroverted math professor looks at your shoes when he’s talking to you.”

Poet and professor Paul Muldoon won points for his appearance in a Tiger magazine video dissecting the recent lowbrow pop hit “Tik Tok,” which recently went viral on the Internet. “I do end up using humor as a teaching device,” he said. “Teaching is about substance, but it’s also about style. There’s a performative aspect to teaching which almost inevitably leads to humor.”

To investigate whether the performative aspect to teaching really did lead to humor, I decided to experience some of these classroom performances firsthand. I followed up on a few recommendations and visited fall-semester classes with high enrollments, reasoning that the funniest professors might attract large audiences. Over several days I traipsed around campus, sitting in on approximately two dozen lectures that spanned a wide variety of subject matters and academic tones.

Though most of this effort consisted of three Ws of undercover reporting — walking, waiting, and wishing — the hours I waited and wished were punctuated, albeit sparingly (imagine punctuation in an e.e. cummings poem) with laughter. Youthful and eloquent Professor Melissa Harris-Perry of “Women, Media, and Contemporary U.S. Politics” scored laughs during a discussion of the importance of full disclosure of one’s past in the Facebook age, noting with awe that “the past three presidents have been high!” Professor Scott Lynch announced the results of midterms in his statistics class matter-of-factly: 44 As, 18 Bs, 16 Cs, 22 Ds, 28 Fs. The class was stunned.

“How would you describe that distribution?” Professor Lynch asked.

The class rabbled loudly and impatiently.

“I think I heard ‘sucks,’” the professor deadpanned.

On a similar statistical note, one of the first lectures I attended was delivered by the economics department’s Bo Honore, who had been recommended as funny by a fellow professor (“And if he’s not funny,” the professor assured me, “then he’s at least really tall”). I settled in at Professor Honore’s econometrics course at 1:30. PowerPoint Slide 1 was entitled “Standard Error of Regression” and was followed by six lines of numbers, Greek letters, WingDings, and non-standard cuneiform. For those of us having difficulty understanding this symbology, the professor wrote a hint at the bottom of the slide. “RECALL,” it began, followed by a colon; and though my math is rusty, I believe that what he wanted us to recall was that Y-squared is equal to the inverse of Pacman and Ms. Pacman eating two candy canes belonging to a moose wearing a party hat.

After 50 minutes of similar mathematical reminders, I am happy to report that Professor Bo Honore is, indeed, really, really tall. Like, at least 6 feet 7.

On my way to another class, I heard belly laughs coming from a room in the basement of McCosh. Sneaking up to the door, I realized with disappointment that the laughter was not the professor’s doing, as I heard the very specific tortured, robotic Spanish that can only mean Introducción al Español. The students were rejoicing in their butchering of Cervantes’ mother tongue; when I arrived outside the classroom, a girl was finishing up a riotous story, apparently about her elaborate attempts to meet her boyfriend that past weekend “al club del Cap y Gown.”

“En Español,” another student pointed out, “es Sombrero y Gown,” and the estudiantes again erupted in laughter.

For better or for worse, this moment marked the end of my quest. Randomness had seeped in and was tainting my findings; that I happened to wander by an open classroom while “Cap” was being translated to “Sombrero” was as arbitrary as it was for me to unsystematically sit in on lectures and judge professors based on snippets of that day’s talk.

I cannot say with any verisimilitude who is the funniest professor at Princeton. After weeks of polling, interviewing, attending lectures, blog reading, and Facebook poking, nothing close to a consensus was reached. I received too many answers, too many candidates, too many professors I just had to talk to. If Princetonians agreed on anything, it was this: first, that the rent is too damn high; and second, that though it is not a clown college, Princeton professors can be funny, and that each student and professor did have that generic memory, that middle-of-the-night fire-alarm humor shock of a great teacher.

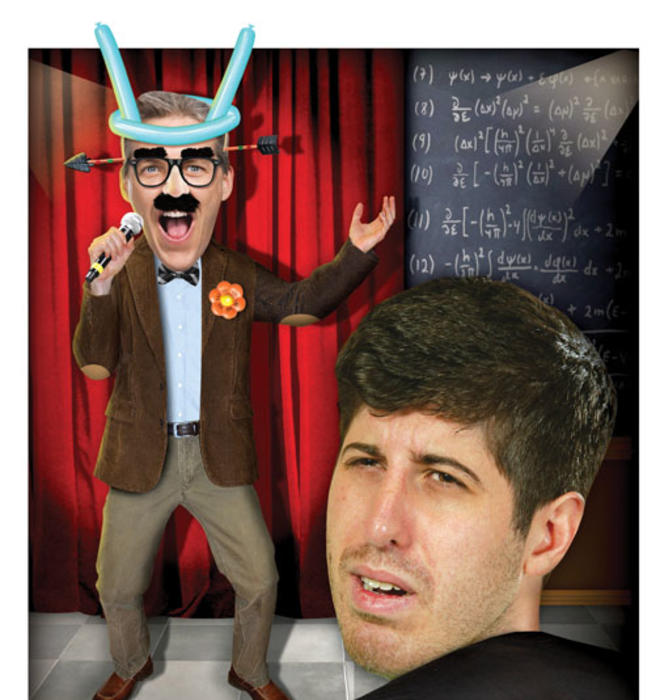

Let the following, then, represent an unranked, biased list of the best fire alarms I talked to or heard about. Ladies and gentlemen — apologies to Dr. Uh-No — your funniest Princeton professors of 2010:

J. Richard Gott *73, who begins one lecture of his Astronomy 101 course by entering the room in casual clothes and hiding his briefcase somewhere in the lecture hall where all of his students can see. He then leaves the room, without explanation, and lets his students sit in the lecture hall, befuddled. Five minutes later, Professor Gott returns in his customary suit and tie and explains to the class that he has forgotten his lecture notes in his briefcase, which he has left at home. “Luckily,” he explains in a thick Southern accent, “I own a time machine!” When he gets home from work, he tells them, he will use the time machine and travel back in time to five minutes before class starts and hide his briefcase in the room. Now, about five minutes ago, did anyone happen to see Professor Gott from the Future and notice where he placed his briefcase?

Jeff Nunokawa is the Robin Williams of Victorian literature. My 15-minute interview with him began with a direct quote from Derrida and ended with an argument for the transformative power of the works of George Eliot. In between, we discussed the importance of Spam to Hawaii, the ways in which he would advise actor Keanu Reeves (in life and in career) if he were to gain his counsel (“like Aristotle with Alexander”), and the cast members of the television show Jersey Shore: “I think they’re fantastically good-looking; I want to know them.”

Theater and drama lecturer Tim Vasen, reviewing the dress rehearsal of a student production: “What this play needs is acting.”

While an undergraduate at Berkeley, Anatoly Spitkovsky of astrophysics participated on a Russian-language comedy team. When I asked him for a sample joke, he apologized that most of the jokes are unsuitable for PAW, because they are in Russian. When I asked Professor Spitkovsky if his students would say that he was funny, he responded as one might expect a left-brained thinker to respond: “I can be more quantitative: 56 percent of class evaluations mentioned my great sense of humor. The rest were more smitten with my good looks.”

A random sampling of the “areas traditionally ... thought to be outside the scope of the field” that Harvey Rosen uses to teach basic economic principles: Beer and marijuana are complementary goods; if the expected utility of a crime is greater than the expected utility of what one would earn by honest labor, then the crime will be committed; and whips and chains are related in consumption. (“I leave it to my students’ imagination to think about how,” Professor Rosen notes.)

German professor Tom Levin has become noteworthy for inventing absurd words and phrases through the addition of suffixes: “the bourgeoisification of cinema,” “the paparazzisation of the political,” “hyperbolical stereotypicalization.” Perhaps most descriptively, when asked to clarify a point he had made, he said: “Yeah, it’s sort of a polysyllabic mouthful.”

Far Side-referencing, oft-nominated psychology professor Danny Oppenheimer says about his comedic professorial origins: “The first time I ever taught a class, back in graduate school, one of the teaching evaluations I got back read: ‘His jokes aren’t funny, but we appreciate that he keeps trying.’ ”

Upon being informed in September that a student had nominated him as one of Princeton’s funniest professors, Bernard Chazelle of computer science said: “This is terrific!!! Almost as terrific as when I hear, in a few weeks from now, that I got the Nobel Peace Prize!”

Most professors were similarly excited (if a tad less so than Professor Chazelle) upon receiving their nominations; many gleefully wondered aloud who had selected them, as though I were delivering roses and chocolate from a secret admirer. But my greatest joy surely was learning, again and again, that for all of the sepulchral and Herzogian classroom days I may have had in Thailand, and all the doubts I had about my classroom funniness, my intellectual and pedagogical superiors had them, too.

“In my lab meetings, we have an award for the funniest comment of the meeting, and also an award for the least-funny attempt at humor,” Professor Oppenheimer told me. “I’ve ended up with the latter award almost every week for the past six years.”

And after all, what are our failures of wit but trifles and minor setbacks when compared to the meaningful work we do? What are our jokes but whims and notes in the margin? This point was eloquently made by a story Professor Rosen told me, which serves as both a coda and a definition of what it means to be a funny Princeton professor:

“I really just can’t help cracking a joke once in a while,” Professor Rosen said, lamenting the curse of all born-comedians. “When I was chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, I did the same when I used to brief President [George W.] Bush in the Oval Office. “

And how did he do?

“I’m not sure how funny he thought I was,” Professor Rosen said, “but at least he never threw me out.”

Jason O. Gilbert ’09 is head writer for the sketch-comedy group Business Flannel. He lives in Union, N.J.

2 Responses

Sun-young Park ’03

10 Years Ago20 minutes of stand-up humor

How is it that Professor Uwe Reinhardt was never mentioned in this article? During a stint my sophomore year when I thought that I, too, could become an investment banker, I enrolled in Econ 102, and Professor Reinhardt’s 20-minute stand-up session at the beginning of each lecture was the only thing that kept me from dropping the class.

Carrie Johnston ’93

10 Years AgoFunny professors

I was interested to read Jason Gilbert ’09’s musings (feature, Jan. 19) on which of Princeton’s teachers are funny. I was eager to read about my favorite Princeton professor, Scott Burnham, from whom I took Music Theory 101 and 102, and was shocked not to see mention of his name.

I’m sure others will write in to nominate their favorite funny professors, and I hope additions can be made to the list. Burnham was extremely knowledgeable, wonderfully engaging, a gifted teacher, and one of the wittiest people (let alone college professors) I have ever met. I loved his class not only because of the fascinations of music theory, but because I invariably ended up laughing a lot.