Learning from Professor Gauss

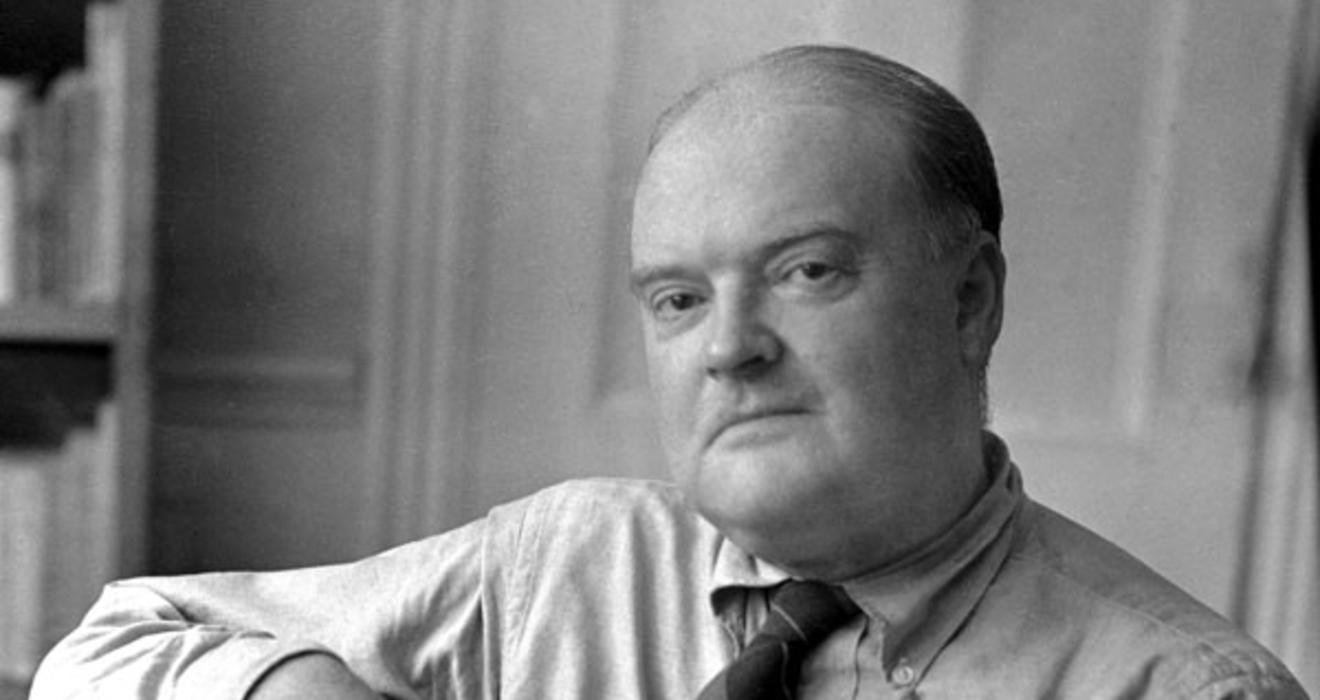

Toward the end of his life, after decades as the country’s preeminent literary critic, Edmund Wilson ’16 campaigned fervently for a publishing project that would make America’s literary heritage universally available. In the words of his biographer, Lewis Dabney, Wilson wanted “a uniform series of affordable high-quality reprints of American classics.” This hope was realized seven years after Wilson’s death with the creation in 1979 of the Library of America, which a New York Times editorial called “Edmund Wilson’s Five-Foot Shelf.” Now, almost 30 years after its founding, the Library of America has dedicated two volumes to Wilson’s essays and reviews from the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s.

Journalism is typically a short-lived form, so it may come as a surprise to find a writer who considered himself first and foremost a journalist enshrined alongside Melville, Faulkner, and Wilson’s friend F. Scott Fitzgerald ’17. But this inclusion is far more than an overdue recompense for lobbying services. Indeed, Wilson shows every sign of being among the enduring American writers of the past century. Writer and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates included his essay “The Old Stone” among The Best American Essays of the 20th Century. Critics and reviewers identify his work as an example of their craft at its best. And if Fitzgerald’s novel of campus life, This Side of Paradise, remains something like required pre-frosh reading, this new collection of Wilson’s work may be more inspiring to alumni in its way, because it shows the central role that the University played in the intellectual development of one of America’s great men of letters.

Wilson arrived on campus from The Hill School with literary ambitions and quickly became involved with the Nassau Lit. Before long he established himself as the central figure of a coterie of students that included Fitzgerald and the poet John Peale Bishop ’16, with whom Wilson later would work at Vanity Fair. Wilson and Fitzgerald wrote the book and lyrics to a Triangle Club show, “The Evil Eye,” in which Bishop starred. (At a performance in Chicago, The Daily Princetonian reported, “300 young ladies occupied the front rows of the house and following the show, gave the Princeton locomotive and tossed their bouquets at the cast and chorus.”)

In those days before creative writing workshops, literary-minded students met in an informal group called the Candlelight Club. At one such gathering during his sophomore year, Wilson met Christian Gauss, then a professor of Romance languages and literature who later would serve as chairman of that department and then as dean of the college. This meeting began a close relationship that lasted until Gauss’ death in 1951, a relationship that had a decisive influence on Wilson and his work.

Gauss came to Princeton in 1905 as one of Woodrow Wilson’s first preceptors, and he retired from the University 41 years later. For students like Wilson, Fitzgerald, and Bishop — who together took his French and Italian literature courses — Gauss cut a romantic figure. “Wilson and Fitzgerald thought most of the English department were old ninnies,” says Princeton’s Henry Putnam University Professor Anthony Grafton. But Gauss was different. As Wilson later wrote in a PAW tribute to Gauss after his death, “He seemed a part of that good 18th-century Princeton which has always managed to flourish between the pressures of a narrow Presbyterianism and a rich man’s suburbanism.”

Gauss had been a journalist in fin-de-siècle Europe, where he covered the Dreyfus case and was said to have tipped glasses with Oscar Wilde. In an essay in The Triple Thinkers: Twelve Essays on Literary Subjects, Wilson imagines Gauss “just back from the Paris of the ’90s, with long yellow hair and a flowing Latin Quarter tie.” At Princeton, Gauss would walk the campus with his dog, Baudelaire. Studying with Gauss, Wilson wrote, was “a voyage of speculation that aimed rather to survey the world than to fix a convincing vision.” In addition to lectures on Dante and Flaubert, Gauss included Walt Whitman in his Romanticism class at a time when other professors still doubted the poet’s place in the canon, and he encouraged Wilson’s interest in French critics Hippolyte Taine and Charles Sainte-Beuve. Throughout his life, Gauss maintained his cosmopolitan outlook, a trait he passed on to his students. In an essay written shortly after the end of World War II, Gauss, by then retired, reflected on higher education and scolded American colleges for focusing their curricula on “how unique, how incommensurable our American civilization is, and how superior to others.”

Gauss “was a legendary figure,” says Grafton. “If anybody stood for Princeton at that time, it was Gauss. He was a model of the Ivy League dean.”

For his part, Gauss was greatly impressed with Wilson, who, he wrote, could not resist a good idea and would gladly discuss writing for hours on end. “He looked upon what we might call the circus aspects of undergraduate life with amused tolerance,” Gauss wrote in a 1944 issue of Princeton’s Library Chronicle dedicated to Wilson. He added that Wilson was a brilliant student who cared little about his marks. Precepts with Wilson were among the liveliest of Gauss’ four decades at Princeton, the professor recalled.

During World War II, Wilson served in Europe as a hospital orderly. His experience abroad and his encounters with ordinary Americans from a wide range of backgrounds would influence his thinking forever. Back in the United States, he took a job at Vanity Fair and asked Gauss to submit an article; he would continue throughout his editing career to solicit works from Gauss for The New Republic and The New Yorker. The two exchanged letters, sometimes several in a week, until Gauss’ death. For a good many years Wilson seems to have sent Gauss every word he published. Although their personal affection for each other is always evident, and these letters contain the occasional congratulations and condolences for family births and deaths, their primary subject is literature, especially each other’s work. (Gauss’ first letter was addressed “Dear Mr. Wilson,” but this soon became “Dear Bunny,” after the childhood nickname by which Wilson was universally known; it would be another 20 years before Wilson felt comfortable substituting “Dear Christian” for “Dear Mr. Gauss.”)

These letters, which are preserved among Gauss’ papers in Firestone Library, show his appeal as teacher and thinker more clearly than his academic writing from the time. He’s learned and quite funny but never pedantic nor condescending, and he writes to Wilson as an equal from the beginning. When Wilson sends a draft of his admiring review of Sherwood Anderson, Gauss complains about Anderson and his contemporaries, “The appeal is too much below the navel. Too much phallus ... Their rumps do not fit the leather of their chairs. How different, Voltaire! How different, Anatole France! You too are different, Bunny.” In a letter dated June 1921, he pleads, “If you don’t come down to Princeton soon, I shall start a demonstration of Princeton fascisti (and you know how numerous they are) in front of the offices of The New Republic.”

In fact, Wilson did return often to Princeton to visit Gauss, sometimes with “Fitz” or Bishop. (“I think he will be fairly tame, because he’s going to have Zelda,” Wilson writes about one impending trip with Fitzgerald. “I trust that she will seize the opportunity to run away with the elevator boy or something.”) During these visits, Wilson recalled in his tribute to Gauss in PAW, “one’s memory of his old preceptorials ... would seem prolonged, without interruptions, into one’s more recent conversations, as if it had all been a long conversation that had extended, off and on, through the years.” After one such trip he told Gauss, “I particularly enjoyed my last visit to Princeton. Such conversation is non-existent in this crazy city [New York].” This conversational quality is one of the great charms of Wilson’s own work. When he writes, for example, about Archibald MacLeish, “His instrument is of the very best make; but, emotionally and intellectually, I fear that a good deal of the time he is talking through his new hat,” one can easily see the remark originating in a walk with Gauss down Nassau Street.

In 1931, Wilson published his first book-length critical work, the classic Axel’s Castle, which traces the roots of writers like James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and T.S. Eliot back to a small band of French Symbolist poets. Though written when some of its subjects were still in midcareer, the book remains one of the best layman’s guides to literary modernism. Wilson dedicated the book to Gauss, to whom he wrote, “It was principally from you that I acquired then my idea of what literary criticism ought to be — a history of man’s ideas and imaginings in the setting of the conditions which have shaped them.” (Gauss said of the dedication, “I do not know that anything in 30 years of teaching has gratified me more deeply.”)

As it happens, this conception of criticism — “a history of man’s ideas and imaginings in the setting of the conditions which have shaped them” — wasn’t much in fashion throughout Wilson’s professional life. Following the lead of T.S. Eliot, the New Critics who dominated the academy in the middle of the century examined works as self-contained aesthetic objects. They might consider novels and poems as part of a larger literary tradition, but they attempted to separate them from the lives and conditions that produced them. As Wilson describes it, “Eliot’s criticism was completely non-historical. He seemed to behold the writing of the ages abstracted from time and space and spread before him in one great exhibition, of which, with imperturbable poise, he conducted a comparative appraisal. This was of course an intellectual triumph, and his essays had their very great value; but it was a feat that could only be performed at the cost of detaching books from all the other affairs of human life.”

Equally misguided to Wilson was the opposite extreme in criticism, where Marxists and other ideologues “merely approve or disapprove when a book does or does not suit their politics.” In an essay on “The Historical Interpretation of Literature,” he writes, “No matter how thoroughly and searchingly we have scrutinized works of literature from the historical and biographical point of view ... We must be able to tell good from bad, the first-rate from the second-rate.”

In the end, this balance has served Wilson remarkably well. It has allowed his work to last, and it makes these volumes from the Library of America a great joy to read. The Shores of Light, Wilson’s collection of his short reviews from Vanity Fair and The New Republic, is subtitled A Literary Chronicle of the Twenties and Thirties, and one of its chief pleasures is its vivid portrait of American culture in the years between the wars, from the apolitical excitement of Jazz Age Greenwich Village to the shock of the stock-market crash to the daily realities of life in its aftermath. Like many, Wilson hoped that the Depression would lead to socialism in the United States, and some of these essays reflect that hope. But others register his disillusionment with the Soviet Union and his repulsion toward Stalin and the Moscow Trials (feelings at which Wilson arrived far more quickly than many of his liberal peers).

At the same time, he is driven above all by his enthusiasm for the work at hand. Reviewing a biography of Stephen Crane, Wilson writes, “What is exciting is to see this life experienced and criticized by a man of first-rate intelligence who was also living in the thick of it — to see its literature tried by the touchstone of a practicing artist.” This is the excitement, too, of Wilson’s work. His rare combination of judgment and wit allowed him to make real-time evaluations of difficult writers that hold up remarkably well today — and to make them with great style. (“For Proust is surely the writer who, more even than any of the romantics, has made heartbreak a protracted pleasure: The romantics’ hearts broke against desolate backgrounds but Proust’s heart breaks at the Ritz.”)

After reading a Wilson essay about H.L. Mencken, Gauss wrote to him, “It is one of the best things you have done. There was background and perspective and penetrations and judgment, all of which I expected. There was also (and more than I expected) a ... sense of enjoyment in what you had read.” When taking Wilson’s final measure as a critic, one returns to this sense of enjoyment. In an essay appropriately titled “Pleasures of Literature,” Wilson summed up the various critical ideologies surrounding him. “The young, usually subject to exaggerated enthusiasms, are today not enthusiastic — not enthusiastic, that is, about books,” Wilson wrote. “I think it a pity that they do not learn to read for pleasure.” In Christian Gauss’ Princeton classroom, Wilson read for pleasure, and he spent the rest of his life passing this lesson along.

Christopher Beha ’02 is a freelance book critic. His memoir of a year spent reading the Harvard Classics, The Whole Five Feet, will be published next year by Grove/Atlantic Press.

No responses yet