The Legacy of Legacy

Family ties are famously strong at Princeton, but changes to admission policies could be coming. Five alumni ponder the future.

In Princeton families, the Tiger connection often extends across generations, and many alumni, secretly or not, hope that their children will someday follow them to Princeton. It may seem like a small thing, but it matters. Legacy preferences — the boost an applicant receives for being the child of an undergraduate or graduate alum — can provide a thumb on the scale in the hypercompetitive field of college admissions.

According to an essay by Princeton professor Shamus Khan published in The New York Times in July, the University accepted around 30% of applicants with a legacy connection in 2018, compared to 5% of applicants overall. As a group, legacies are more likely to be white and to come from wealthy families than others in their entering class. Academically, they seem to be qualified. The Daily Princetonian, citing Class of 2023 and Class of 2026 surveys, found that legacy admits had higher SAT scores and earned higher undergraduate GPAs than their non-legacy classmates. And make of this what you will: They were also more likely to work in public service or for nonprofits after graduation.

Although the legacy preference in American higher education dates back a century, and has been controversial for nearly as long, it has come under even greater scrutiny since the Supreme Court last summer banned colleges from explicitly considering race, ethnicity, or national origin in admission decisions. Fearing that entering classes will be less diverse as a result, critics have called for ending the legacy preference on the grounds that it provides an unfair leg up to applicants who are already advantaged. Defenders counter that the legacy preference helps bind alums to the University and should not be ended in the name of diversity just when a growing number of minority alums are beginning to take advantage of it.

Even before the Supreme Court’s ruling, several colleges and universities, including Johns Hopkins, Pomona, Amherst, and Wesleyan, decided to end their legacy preference. Since last summer, the Department of Education has opened a civil rights investigation into whether Harvard’s legacy preference discriminates against Black, Hispanic, and Asian applicants, and Oregon Sen. Jeff Merkley *82 has introduced legislation that would prohibit its use at institutions receiving federal funds. At Princeton, the Board of Trustees created an ad hoc committee to review the University’s admission policies, including legacy admissions, in light of the Supreme Court’s decision.

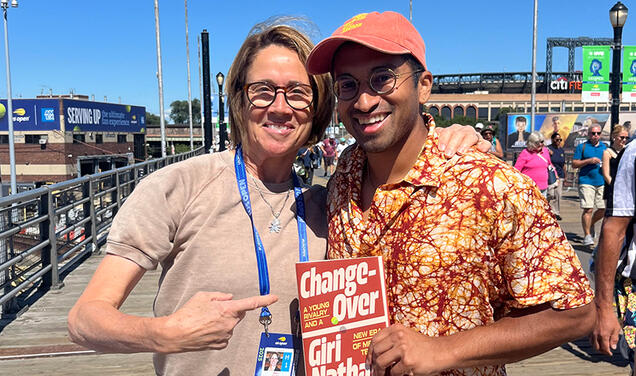

Given the strong feelings that exist on both sides of this question, PAW invited four alums — Lolita Buckner Inniss ’83, Rachel Kennedy ’21, Nathan Mathabane ’13, and Jeffrey Young ’95 — to discuss legacy preferences and whether Princeton ought to continue them. The conversation was conducted on Zoom and moderated by PAW senior writer Mark F. Bernstein ’83.

Bernstein: Lolita and Rachel, can you talk about your own experiences with legacy admissions?

Lolita Buckner Inniss ’83: I’m the first person in my family to go to college, and my coming to Princeton was largely by accident. Yale was actually my first choice. Why? Because I had heard of it, and someone told me it was great. I was accepted, and then in July, shortly before classes started, I met a Princeton alum who told me what a great place Princeton was and that it was probably not too late for me to get in. So, I wrote to Princeton, asked if I could come, they said yes, and I withdrew from Yale. I turned up on Nassau Street a few weeks later, carrying my duffel bag and my basketball and wondering what had happened to me because I had no clue about any of this.

I’m now married to a classmate [Daryl Inniss ’83] and we’ve been together since freshman week. We had kids really young, a set of twins. I think the first time we went back to Reunions they were both in strollers. One of them, Christopher [Inniss ’09], announced when he was 10 years old that he was going to Princeton, probably because of the Reunions experience. My husband and I strongly encouraged him. In fact, maybe one of the hardest things in our family life was when only one of the twins wanted to go to Princeton.

One of the most thrilling things that has ever happened to me is when we got the big envelope for Christopher. He was still at school, so I went out to the mailbox, brought the letter into the house, and fell straight on the floor. My mind was blown. It meant a lot to me that my son went to Princeton, and I think it’s fair to say that he was a lot more prepared to attend than either I or my husband had been, because he grew up with upper-middle-class parents.

My other son, who didn’t go to Princeton, said that my husband and I bleed orange and black. Yeah, maybe. Christopher being a legacy certainly has tied me to Princeton even more closely. If they got rid of legacy admissions, it wouldn’t be the end of the world. I do think, however, that it creates a bond within legacy families that can’t be replicated.

I would be cynically amused if they were to end legacy admissions now when there are finally enough alums of color, especially Black people, to take advantage of it. To end it now really would cut off that opportunity.

Bernstein: How about you, Rachel?

Rachel Kennedy ’21: I’m the seventh person in my family to go to Princeton. So, I’ve had six of the most influential people in my life talking about the ways that they love the school and the ways that they struggled there. Growing up, I was intimidated by that and never wanted to go to Princeton. My dream school was Georgetown, but that started to change in high school, in 2016, when my dad [Randall Kennedy ’77] gave the baccalaureate speech.

I went. I saw Princeton. I saw the most beautiful school ever. I felt that community spirit. Both of my cousins had gone to Princeton, and they also went back to hear my dad speak. Seeing just how much the three of them enjoyed being back together was such a powerful experience. And so even though my twin brother was the first one to be interested, I decided to apply too. We did not think the school was big enough for both of us, so he ended up going someplace else. I loved Princeton. It was an incredible experience.

In terms of the legacy question, though, I do think it should be abolished because stories like ours and yours, Dean Buckner, are the minority. Seventy percent of people who benefit from the legacy preference are white. It’s just another way to give even more opportunities to people who already have lots of them. This is not a popular stance in my family, by the way. There’s a lot of pride and a lot of spirit around the school in general. I celebrate that and I’m grateful for it in my life. But I think with the repeal of affirmative action, the school has to do as much as possible to promote diversity.

Another note from my experience: One of my main friend groups from Princeton is a group of eight students. We’re very diverse in lots of ways: Asian kids, Black kids, queer kids, the whole gamut. That said, six of us are also legacies. We all met from different areas of the campus, but for some reason legacies gravitate toward each other and that limits the college social experience. I love those friends. I’m grateful for them. They made Princeton the place it was for me, but they are not the diverse group that college could be providing.

Bernstein: [President] Christopher Eisgruber [’83] has said that legacy admission is “an important part of who we are as an institution that creates a community that persists long after graduation. Legacy works in our admission process as a literal tiebreaker.” Nathan, from your experience, is that how it works?

Nathan Mathabane ’13: I think that’s accurate. Obviously, anybody who’s getting into the school is academically impressive across a variety of metrics. That being said, with the volume of applications we were getting, we had to be very deliberate about who got that full look, that full analysis by the admission committee. Most legacy applicants were looked at in their entirety whereas other applicants, even those who might have appeared the same on paper, were not given that full review.

Bernstein: You’re a college counselor now at a prep school. Do you tell legacy kids to be sure to check that box when they are applying to a parent’s alma mater?

Mathabane: Yes, except that kids don’t necessarily want to go where their parents went. Sometimes they’re not checking that box because they’re not applying in the first place. I think there is this notion that legacy students are always fired up to go wherever their parents went. Maybe that’s a very Princeton thing, but it’s not always the case.

Bernstein: One of the arguments in defense of legacy admission is that it that leads to more donations from alumni. Does that justification stand up?

Jeffrey Young ’95: There was a book that came out a few years ago called Affirmative Action for the Rich: Legacy Preferences in College Admissions by Richard Kahlenberg, who has looked into that argument. He said the research isn’t so conclusive that the legacy preference directly leads to more donations. I know Princeton has a very good tradition of having alumni give back, but I think it’s less clear whether this is true elsewhere.

One college that has decided to retain its legacy preference is William & Mary, which happens to be where my parents met. William & Mary defended their decision in part because they said that legacy students who are admitted are much more likely to accept, which boosts the school’s ranking. All these highly selective colleges offer incredible opportunities, but they also need to fill their classes and avoid a lot of waitlist stress.

Kennedy: You bring up a great point, Jeff, that different schools have different reasons for keeping legacy. Princeton doesn’t have to worry about filling its entering class, and it has such a huge endowment that it doesn’t need to rely on admitting wealthy students whose parents can pay full tuition. Princeton occupies such a privileged position, which would make it easier for Princeton to get rid of legacy admissions, though I do recognize that other schools are not in that position, which complicates the conversation.

Bernstein: College admission has never been purely meritocratic. It helps if you play the clarinet and the school you’re applying to needs a clarinetist for the orchestra. It helps if you’re a field hockey goalie and they need a field hockey goalie. Given this, what’s wrong with giving a small boost to children of alumni as well?

Mathabane: I think it’s all about the lottery of birth. You could argue that the clarinet player or the field hockey goalie had to do something to earn that distinction, whereas the legacy student, just by virtue of who they were born to, has had a thumb on the scale from the time they were in the delivery room. We do make these arbitrary concessions to different extracurriculars, but there’s no extracurricular for having been born to Princetonians.

Inniss: I get what you’re saying, Nathan. For me, legacy admissions are a more direct route to what is still going to happen because let’s look at those field hockey goalies and excellent clarinet players. You’re right, they would have had to have worked hard to achieve excellence in those areas. But the people who are most excellent in those areas are also typically white, wealthy, and well-connected — I call them the three Ws of getting into a top school.

If anything, taking away legacy admissions makes those realities less transparent. Again, I look at my own kids. All three were top classical musicians. Some of that was because they were born with amazing music genes and intellect genes, but my husband and I also spent many thousands of dollars on lessons and training. They also never had to hold down a job while growing up, and I could argue that without those benefits they wouldn’t have been able to develop their skills they way they did.

Rachel, you mentioned that six of your eight closest friends were legacies, but let’s take away legacy. Those six out of eight probably would have been admitted to Princeton anyway because I’m guessing you are all excellent students. I don’t think legacy admission by itself is as unfair or unjust as it’s often made out to be because it’s just one factor, and often a relatively minor one, that describes people who still have all kinds of outstanding opportunities and characteristics to help get them into these places.

“If Princeton does away with legacy admissions, as indeed may happen, there will still be lots of us who send our children there. Why? Because we have a strong attachment to the place, and thanks to all the advantages our children have received since birth, they will still be very likely to get in.”

— Lolita Buckner Inniss ’83

Bernstein: Xochitl Gonzalez wrote in The Atlantic recently that “ending legacy admissions will most likely mean that wealthy children whose parents went to Brown will go instead to Yale or Columbia.” Is that a fair way of looking at it?

Mathabane: I would say that reading of the situation is probably true. There are no quotas in the Princeton admissions system. No one says, ‘We need X number of this student, X number of that student,’ but we are looking to meet different institutional priorities around social diversity, and we also want to do right by our athletic program. We do have certain buckets that we’re trying to fill in each class. But we would never be looking, say, to decrease the number of Pell-eligible students or decrease the number of lower-income students in favor of admitting a legacy applicant.

Kennedy: This is already a competition among the most affluent of society, why do something to further benefit them?

Bernstein: If the University were to do away with legacy admissions, would it change the “special sauce” that binds so many alumni to Princeton? Lolita, you’re shaking your head.

Inniss: No, because the cynic in me says that there are still going to be a huge number of children of Princeton alums who apply and they’re still going to have tremendous advantages in preparation and resources.

Young: Princeton has changed so much since I was a student, and it’s going to be a profoundly different place regardless of whether we do away with legacy admission.

The social makeup of the University has changed completely over the last 30 years and that is going to continue. Princeton will look very different in 2050 regardless of what happens just because of the type of students who are being admitted.

I do think the reason colleges are rethinking legacy admissions now is because of the Supreme Court’s decision ending affirmative action. If schools can no longer explicitly take race into consideration, will the legacy preference become even more unfair? It seems like a moment to ask tough questions about every piece of the admissions puzzle, including how athletes are treated, how early decision works, all kinds of things.

Bernstein: One of our fellow alums, Sen. Jeff Merkley, has co-sponsored legislation that would ban colleges receiving federal funds from considering legacy in admissions. Is this an issue that deserves a response from the federal government, or should Princeton be left to decide on its own?

Inniss: I don’t think this is something that requires a legal response. If Princeton does away with legacy admissions, as indeed may happen, there will still be lots of us who send our children there. Why? Because we have a strong attachment to the place, and thanks to all the advantages our children have received since birth, they will still be very likely to get in.

Here’s something I’ve thought about, though. What if we just said, after an applicant has reached a certain level in terms of test scores or grades or some other measure of qualification, we’re going to throw everyone in a big barrel, and we’re going to pick our entering class out of there? In some respects, people would say, ‘Oh, that’s fair.’ But when you consider that there’ll still be large numbers of highly educated people in that barrel, many of whom have parents who went to schools like Princeton, they’re still going to be statistically more likely to get chosen.

I just don’t know if this particular aspect of undergraduate admissions is worth the kind of attention we’re giving it. If we care about things like access, fairness, and historical injustice in higher education, this is not the field on which we should be fighting.

Kennedy: I believe there was a study done after Amherst did away with its legacy preference [in 2021], and the number of legacy students in their incoming class fell significantly. Lowering it at Princeton could also have beneficial effects. I agree, it’s not a hill to die on, but I do think it’s a way to avoid giving another privilege to people who already have a lot of it.

Young: There is also a legal question now. The Department of Education has opened a civil rights investigation into Harvard’s legacy admissions policy because a complaint was filed by activists who allege it discriminates against Black, Hispanic, and Asian applicants in favor of white, wealthy ones. They’re arguing to extend the logic of the Supreme Court’s decision abolishing affirmative action in college admissions, to say, essentially, if a racial preference is not legal, then how can a legacy preference be legal? If you eliminate one, how can you keep the other?

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

7 Responses

David S. Gould ’68

1 Year AgoIn Defense of Legacy and Donor-Funded Aid

I am writing to agree with my classmate John Dippel’s letter pointing out the advantages of so-called legacy admissions.

When I was at Princeton, I came across a bunch of students with a bullhorn demanding changes at Princeton including the elimination of legacy admissions. When the speaker finished, I grabbed the bullhorn and said:

“Every professor I have had grades on a curve. I don’t want to spend my years here competing with geniuses. I say bring on more legacy admissions!”

For different reasons, my support for legacy admissions have not changed. I have no dog in this fight because both of my wonderful sons are autistic. (When I saw the Princeton tuition this year, it was the first time I saw any benefit in my sons being autistic).

First, at my recent 55th reunion, I met many legacies of my classmates and it confirmed John’s statement about how truly qualified and wonderful they all were.

Second, legacy admissions are often twined with affirmative action for those who are and would be large donors to Princeton. Facially that seems unfair to those without the silver spoons in their mouths at birth. But it is precisely due to those generous donors that Princeton, Yale, and Harvard are among the colleges that no longer give out student loans. Every penny of the scholarship is free from the yoke of future crushing debt. The beneficiaries of that largess are precisely the less and underprivileged students that have so benefitted Princeton and made it the multicultural institution it is today.

E. Bruce Hallett III ’71

1 Year AgoInside a Legacy Family

The college of your parents occupies a significant space in the firmament of a family.

I was the son of a proud Princetonian (EBH Jr. ’44) and I’m pretty sure his legacy was the reason I was admitted to the Class of ’71. For my five children, I was known as both a one-time cheerleader for Princeton teams, and a figurative one in describing to them the benefits I got from four years at the school.

Yet when my oldest daughter, a cum laude and tri-varsity athlete, graduated from Phillips Exeter in 2002, neither her accomplishments nor our family legacy were enough to earn her a place at Princeton. She matriculated at Brown, but I judge that she never overcame the sense that she had disappointed me, my father, and even her siblings. None of my other children applied to Princeton.

We lost both affiliation and affinity with the school. The belief we carried that the school valued our family and our history there evaporated. Rather like a man whose wife of many years departs for someone new, I felt not just disappointed, but somehow embarrassed.

Martin Schell ’74

1 Year AgoWhat About Siblings?

This quasi-interview is more fragmented than Mark Bernstein’s other articles, which usually are excellent. Nevertheless, it outlines some key points.

Several interviewees and Inbox commenters already noted that being raised by a Princeton parent generally means at least inculcation of an attitude of intellectual curiosity, if not also the financial means to engage in various “culturally enriching” activities, which might even lead to young stardom.

It was also noted that minority groups now enjoy parental legacy. PAW’s coverage of Reunions had a photo of a Black alumna from ’71 with her alum daughter and alum granddaughter. The river is already flowing, so maybe we don’t need to push it anymore (a nod to poet Barry Stevens).

Neither the interview article nor the comments mentioned sibling “bonus.” Michelle Obama ’85 is quoted to that effect in her Wikipedia page (with a citation tracing back a Newsweek story), and at least one inside source told me that Ivy Admissions will generally look favorably on an applicant whose older sibling successfully managed a standard course load (or already graduated). This is particularly true for “first generation in my family to attend college,” which is now a form of affirmative action that applies to all races.

Jonathan Remley ’95

1 Year AgoPrinceton On Its Own Merits

The numbers around legacy admissions rates and class representation are telling. But focusing the debate on “legacies as a percent of the incoming class” vs. “potential legacies denied admission” glosses over two key cohorts — “potential legacies who did not apply” and “potential legacies who were accepted but chose not to attend.” Financial considerations aside, perspectives shared by members of these two categories might decompress the wider issue. We know well that Princeton cannot accept all qualified applicants, but we rarely hear why Princeton isn’t the ideal fit for all admittees, even those with family ties.

John V.H. Dippel ’68

1 Year AgoWhat Legacies Add

Like many alumni, I have mixed feelings about the issue of “legacy” admissions (“The Legacy of Legacy,” December issue). As the father and son of Princeton graduates, I am proud (and grateful!) that this attachment to and affection for the University has been sustained over three generations. However, I also understand that, as Princeton has grown more diverse, the idea of giving alumni children an edge in admissions smacks of indefensible privilege — unearned and inherited, like a country estate.

Perhaps we need to ponder what “legacy” really means and why it should remain important to Princeton. In current parlance, the word is regrettably misleading: It connotes an advantage based upon status and not merit. Statistics belie this view: As the recent PAW article on this subject confirmed, alumni sons and daughters more than measure up academically and in all other salient regards. What they add to the University is a sense of time — a living connection with what Princeton once was and what it will become. As a result of coeducation and the greater emphasis put on attracting nontraditional students, this link to the past has become greatly enriched. Nothing is more gratifying to me than knowing that loyalty to Princeton now encompasses a much more varied group of students.

Without this personal awareness of the past, universities and other communities inevitably become impoverished — their raison d’etre reduced to what they are only in the present moment. Excellence can continue to flourish with this limitation, but its roots will be more shallow.

Jonathan B. Rickert ’59

1 Year AgoFamily Ties to Princeton

The cover of the December issue of PAW could represent my family (minus grandpa’s cigar!) — my grandfather, father, uncle, stepfather, his brother, my two brothers, stepbrother, daughter, and myself all attended Princeton. As my 10th grade granddaughter approaches time for the college application exercise, I wonder whether or not she will be accepted if she applies to Princeton. I can see various pros and cons concerning legacies and am agnostic about their retention or elimination. Either way, I hope that my talented granddaughter will apply and gain admission based on what she has accomplished and all that she brings to the table.

Lawrence W. Leighton ’56

1 Year AgoPositive Effects of Legacy Admissions

The legacy category in Princeton admissions is a major positive for the University, its students and its alumni.

One of Princeton’s important and unique strengths is its culture of being a family and the cohesiveness of its student body, as well as the loyalty of its alumni. Accordingly, a loss of the legacy category would be far more damaging to Princeton than it would be to other universities.

I came to Princeton on financial aid from parents with barely a high school education and I learned a great deal from my legacy classmates. They not only enhanced my knowledge of Princeton’s history but also taught me the many advantages of the extended Princeton family. The implied negative statement that legacies come from only wealthy white families is, of course, outdated. Princeton legacies now include children of Asian alumni, African-American alumni, Hispanic alumni, and others.

The legacy category for Princeton admissions is a commanding strength and it is imperative that it be maintained.