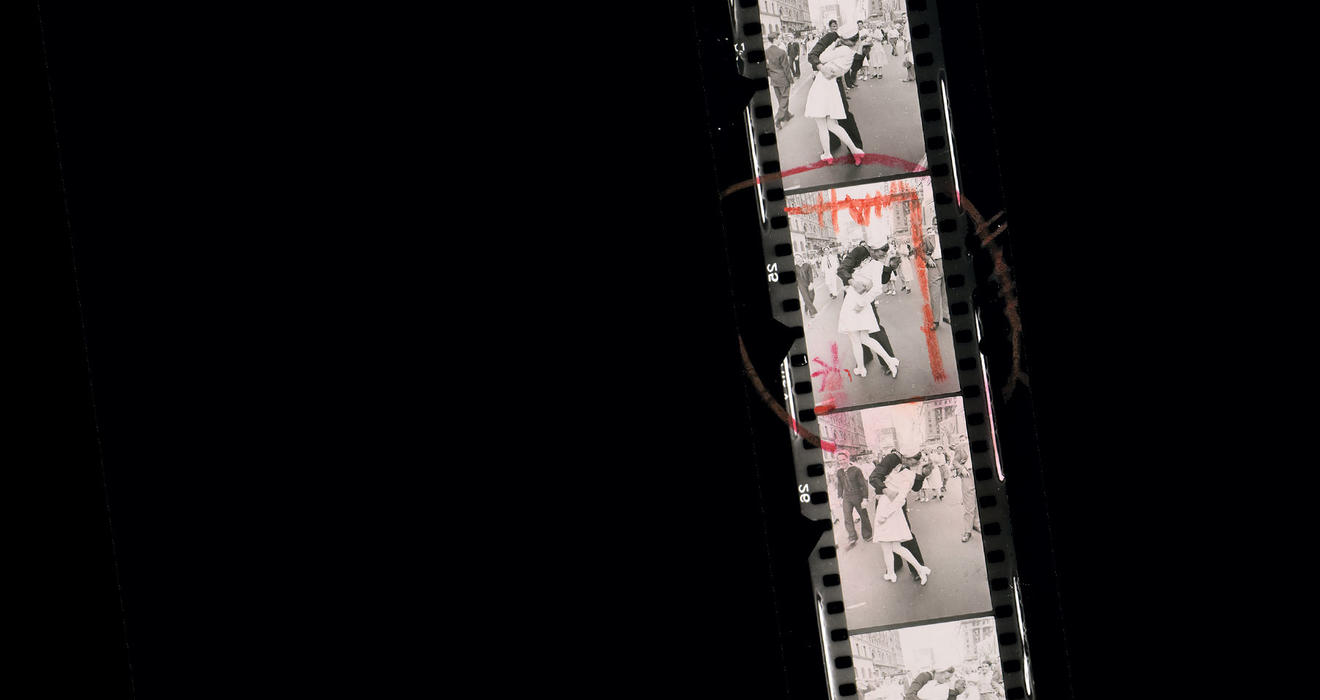

Even if you were born after World War II, there’s a good chance you can clearly picture events of the time. The aerial views of the atomic bombs detonated over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The sailor kissing a nurse in Times Square after Japan surrendered. The view of Adolf Hitler’s bunker after he and Eva Braun committed suicide there.

“To this day, iconic images are part of what gives us a sense of the news and the happenings in our world,” says Katherine Bussard, Princeton University Art Museum’s photography curator. Much of photography’s influence, she says, is because of the legacy of LIFE magazine. As the preeminent picture magazine of the 20th century, LIFE featured about 120,000 photo essays, selected from around 24 million photos. At its peak in 1966, LIFE sold 8.5 million copies each week.

On Alumni Day, the museum opened “LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photography.” Using about 170 images and other objects, the exhibition, which runs through June 21, explains why LIFE was both extraordinarily popular and visually revolutionary — not just in its coverage of news events, but in its photography of cultural figures, politicians, and ordinary people and their communities. “There’s a prominence given to photographers from the start,” Bussard says of the magazine, founded in 1936. Especially in the days before television sets were commonplace, the images in LIFE helped shape people’s views of the world.

The Art Museum is the first to have gained access to LIFE’s complete picture collection, and it’s the first to dive into publisher Time Inc.’s corporate archives, which recently became available in the New-York Historical Society’s library collection. The exhibition examines LIFE’s weekly run, from 1936 through 1972. Though the magazine stopped monthly publication in 2000, the exhibition shows that its legacy — prioritizing photography and visual stories — remains with us today.

Anna Mazarakis ’16 is a podcast producer.

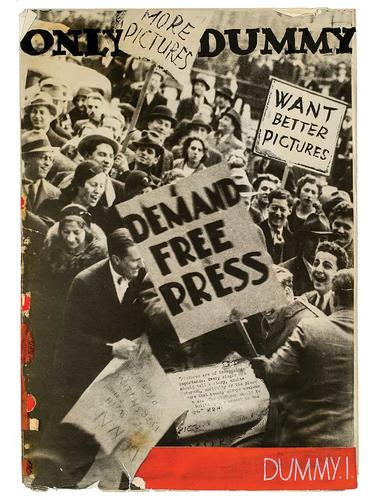

Cover Of Dummy I, Pre-1936

Kurt Safranksi

Before Time Inc. could launch LIFE magazine, the company created an Experimental Picture Department to figure out what a new picture magazine could look like. An integral part of that process included the creation of a “dummy,” or a mock-up. The proposed magazine’s earliest iterations laid the framework for dynamic photographic layouts. They also introduced regular features like “Picture of the Week” and “Life on the News Fronts of the World.”

“The images used in the dummies were meant to be more evocative of what it looked like to harness the power of great photographs and great photographers,” Bussard says.

Kurt Safranksi, who was part of the Experimental Picture Department, created this dummy and would later pitch it to the publisher, Henry Luce.

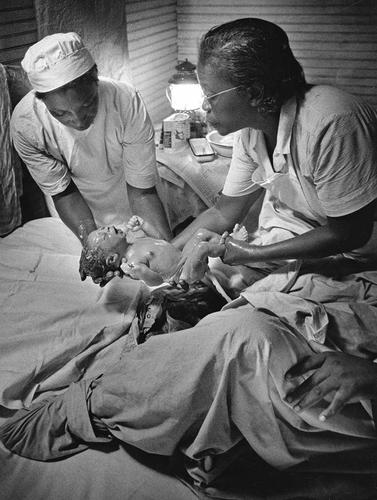

Nurse Midwife Maude Callen Delivers a Baby, Pineville, South Carolina, 1951

W. Eugene Smith

Before the days of smartphones and digital cameras, LIFE photographers might have felt constrained by the number of film frames they had left. Not W. Eugene Smith. For this assignment alone, he shot more than 2,600 negatives. His pictures highlight the tangible tasks of a nurse midwife, Maude Callen — as in this image where she’s helping deliver a baby, and another of a baby in a makeshift crib. They also feature the challenges presented and overcome in her everyday life and work — for example, walking through woods to get to a patient and ruining several pairs of boots.

“It becomes clear just how demanding and how challenging providing health care was for these licensed midwives,” Bussard says. “That’s what Smith is seeing.”

For Smith, this assignment meant taking a midwifery course before spending a month capturing Callen’s life. The Princeton exhibition suggests other ways he prepared: It includes the outline created before the story was assigned and a letter Smith wrote to his editor about his progress, along with two of Smith’s contact sheets — where the film’s negatives were printed — and other vintage press prints in the photo essay.

At the Time of the Louisville Flood, 1937

Margaret Bourke-White

After the 1937 Louisville flood, Margaret Bourke-White was on the scene to cover its impact. The “Great Flood” affected more than 150 cities along the Ohio River and contributed to about 500 deaths. In Louisville, two-thirds of the residents were evacuated.

Bourke-White was one of the first four staff photographers hired by publisher Henry Luce for his new picture magazine in 1936, and her photograph of the Fort Peck Dam in Montana was chosen for the first cover.

Documenting the flood in Louisville, Bourke-White captured submerged cars and people traveling in boats, but the image LIFE led with distanced the flood victims from visible devastation. Instead, they’re standing in line, waiting for bread. But there’s a larger message in the image: Bourke-White framed the line of black flood victims below a billboard featuring a white family. “World’s highest standard of living,” says the sign. “There’s no way like the American Way.”

“There’s a real emphasis on the disparity between advertising and reality, white and black, prosperity and struggle,” Bussard says.

In the exhibition, a small tablet will display the digitized negatives of other photographs Bourke-White took during her assignment. That way, visitors can understand what Bourke-White was drawn to photograph and the importance of how she framed her images.

Normandy Invasion on D-Day, Soldier Advancing Through Surf, 1944

Robert Capa

Only four photographers received permission to document the Allied landing in Normandy, including Robert Capa, who traveled with the U.S. Army between 1941 and 1946. Most of his film was damaged during the invasion, leaving few images from his perspective of the landing, where Capa joined 34,250 troops wading onto Omaha Beach. The detailed notes he sent back to LIFE magazine’s offices were censored by the military. This image shows Pfc. Huston Riley, 22, who was wounded in the invasion; after taking the photo, Capa and a soldier assisted Riley.

The picture is part of an exhibit that examines the work of embedded photographers during war. Capa’s work abuts that of Larry Burrows. Both photographers were killed on assignment in combat zones: Capa when he stepped on a landmine in Vietnam, and Burrows when the helicopter he was flying in was shot down over Laos.

“It’s incredibly high-risk photojournalism,” Bussard says, adding that in the exhibit, “there’s not a moment where it feels like they’re standing to the side observing.”

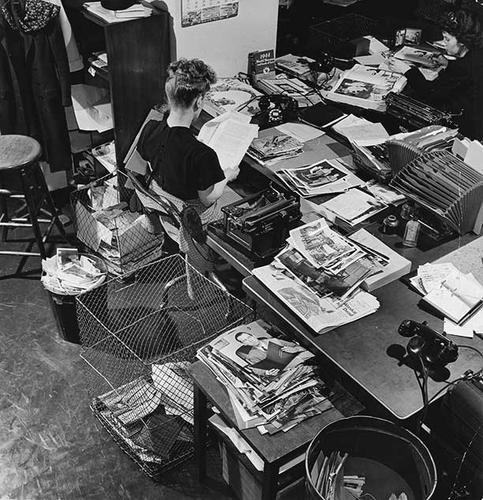

LIFE Photo Editor Natalie Kosek Reviews Photographs, 1946

Photographer unknown

Every part of her desk is piled high with photographs. We don’t know much about the life of the desk’s occupant, “picture researcher” Natalie Kosek, but Bussard says her tasks would have included sifting through images and then helping to decide which ones should be placed in the magazine’s layout. All the picture researchers of the time were women.

Though LIFE magazine was mostly segregated by gender, women had significant responsibility. Peggy Sargent, for example, began as a secretary and eventually became picture editor. She was in charge of reviewing the film negatives, and “photographers would joke that she held their careers in the palm of her hand,” Bussard says.

The Princeton exhibition dives into the role of women at the magazine, both behind the camera and behind the scenes. From the researchers who compiled information for photographers going out on assignment, to the team that filed and organized the picture collection archives, women played an important, yet often unrecognized, role in the production of LIFE.

Gang Member With Brick, Harlem, New York, 1948

Gordon Parks

LIFE magazine’s readers were predominantly white, middle class, and high school- or college-educated, so the stories featured in the magazine often promoted those perspectives. In 1948, Gordon Parks — who had never photographed for LIFE before — proposed a different kind of story: a photo essay on the Harlem gang wars. The story’s success prompted LIFE to hire Parks as its first black staff photographer.

In the exhibition, the photograph is accompanied by other images in Parks’ pivotal photo essay, including those of a gang leader with his family, as well as shots that portrayed the more dangerous aspects of life in a gang. This image, for example, shows the scene of a gang member about to be ambushed.

“To me,” says Bussard, “it’s an arresting moment where it seems very clear that something is about to happen.” There’s an alertness in his body and tension in his arm as the gang member looks toward the shaft of light and prepares for whatever comes next.

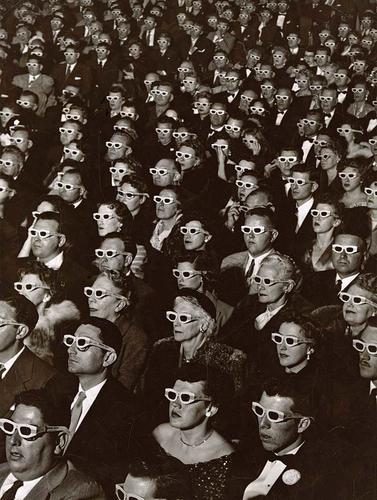

Audience Watches Movie Wearing 3-D Spectacles, 1952

J.R. Eyerman

Sometimes, a photographer might be assigned to cover one story, but the photograph ends up telling a completely different one. That was the case with this image: J.R. Eyerman was sent with a reporter to cover the screening of the first full-length, color, 3D movie, Bwana Devil. The reporter’s notes make clear that they are meant to be covering the technology of 3D film.

“How does the photographer capture that?” Bussard asks. “Well, it’s sort of understandable that he turns his attention to the audience that’s experiencing the technology. So, in some ways, it seems like a very smart move.”

LIFE printed the image on a full page, a suggestion that readers should linger on the photograph.

1 Response

Joseph E. Illick ’56

5 Years AgoIn Appreciation of ‘LIFE’

I appreciated the feature on LIFE at the University Art Museum. Like most of my classmates, I suspect, LIFE was my avenue to national and international affairs as a boy. And I’m happy to be able to say that one of those classmates, Peter Young ’56, was LIFE’s first official correspondent to the USSR after World War II.