A life in opera

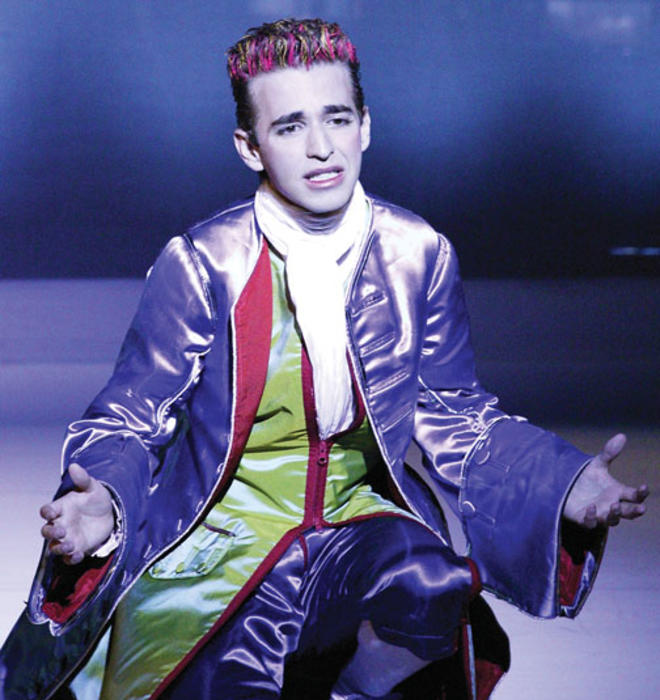

Thanks to his distinctive voice, Anthony Roth Costanzo ’04 seems poised for a career on the stage

In the fall of 2004, Anthony Roth Costanzo ’04 and filmmaker Gerardo Puglia entered a dark, 18th-century theater in Naples to shoot a scene for a documentary about Costanzo’s senior thesis. That a documentary would be made about a student’s thesis was unusual, but so was the thesis itself: an operatic portrayal of a fictional castrato — a singer who was castrated before puberty to maintain his high voice. On this day in Naples, however, the visitors felt dejected: They had been allotted only one hour to film, the lighting was horrible, and noisy workers were dismantling sets from the last production.

The workers were oblivious to Costanzo — that is, until he mounted the stage and began to sing an aria. “All of a sudden,” Puglia says, “the workers put down their tools and the lights started to come on.” Puglia requested and received a spotlight on Costanzo. The noise stopped. The workers postponed their work taking down the set and turned to help Costanzo and Puglia, providing a painted backdrop for the film.

The two ended up filming most of the day.

The voice that so struck those Italian workers has captured the attention of audiences and critics alike: Costanzo is among the small group of opera singers who are countertenors — men who sing in what’s usually a woman’s mezzo-soprano or alto range. In the past year, he’s won six major competitions, including the prestigious Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions program last spring, which has launched many an operatic career (past winners include the soprano Renée Fleming and mezzo-soprano Susan Graham). In that competition’s 56-year history, only four winners have been countertenors. In 2008, Costanzo was the first countertenor to win another major vocal competition, the Opera Index Competition.Like most countertenors, Costanzo specializes in Baroque operas and sings roles originally written for castrati. He enjoys the musical freedom of Baroque opera, comparing it to the improvisation that is such a large part of jazz. A singer in the 17th or 18th century was expected to insert his own melodic creations during the performance, Costanzo says. (Today, he explains, that ornamentation is incorporated during rehearsals.) Handel, who wrote many roles for castrati, dominates Costanzo’s repertoire, though the young performer also sings roles by Claudio Monteverdi, Henry Purcell, Benjamin Britten, and György Ligeti. Between the “hundreds and hundreds” of roles written for castrati by Baroque composers and the increasing number of modern and contemporary composers writing for countertenors in operas, the repertoire for his voice type is “almost limitless,” Costanzo says.

Costanzo used his time at Princeton to become an expert on the lives and music of the castrati, writing his junior paper on the topic and then producing an exceptional senior thesis: a one-night-only production in Richardson Auditorium of The Double Life of Zefirino. Costanzo wrote the dialogue and sang Baroque arias that told the story of a character trying to come to terms with different aspects of his life — both the stardom and the sense of enslavement to his art that comes with castration. Castrati were the “rock stars of their era,” he explains. There was a “certain virility” to their voices; women went crazy over it, “and in some cases, men, too.” Though castrati were most popular during the Baroque period, from about 1600 to 1750, they appeared in church and on the operatic stage well into the 19th century.Later, when the early-music movement of the 1950s and 1960s renewed interest in Baroque opera, directors faced the dilemma of having to cast roles that had been written for castrati. Initially the solution was to assign these roles either to women — usually mezzo-sopranos — or to transpose them an octave lower, so they could be sung by tenors or baritones, explains music professor Wendy Heller, who directs Princeton’s Program in Italian Studies and was Costanzo’s thesis adviser. But soon the countertenor began to emerge.

Countertenors sing in what is called the “head voice” — so called because the voice resonates from the head instead of the chest. It’s sometimes known as falsetto, though scholars have been debating distinctions between those two terms for years. Falsetto is Italian for “false little voice,” but Costanzo says there is “nothing fake about the countertenor voice.” Even he finds it difficult to describe the voice, as each countertenor has his own sound. It has “a decidedly male sound,” he says. “It is a sound that you can tell is not a woman, but it is in the same register that women sing in.”

Costanzo was introduced to the countertenor voice when he was about 13 years old and singing in his first opera, The Turn of the Screw, based on the Henry James novella, at the New Jersey Opera Festival. He played the role of Miles, a conflicted boy who is vacillating between innocence and total corruption.

At the time, Costanzo already was on his way to a career in acting and musical theater. His parents — both psychologists at Duke University — signed him up for piano lessons when he was 6. A piano teacher would have him sing the music before playing it himself, and by age 8, he declared to his parents that he wanted to become a singer. Not long after that, he won a part in a community-theater production of The King and I, and over the next two years performed in local and regional musical-theater productions, landed a New York agent, and won a part in a Broadway national tour of Falsettos. He was 11.

After Falsettos, he moved to New York City and enrolled in the Professional Children’s School in Manhattan, designed for children involved in professional performing arts, entertainment, or competitive sports. That first year, his parents alternated weeks living with him; later, they adjusted their teaching and sabbatical schedules to support their son.

Costanzo knew little about opera when he auditioned for The Turn of the Screw, but he impressed Michael Pratt, the opera’s music director and conductor and, at Princeton, conductor of the University Orchestra and director of the Program in Musical Performance. Pratt recalls casting the adolescent Costanzo for this “very dark opera” because of his maturity, dedication, and focus. “He was thoroughly professional, completely prepared, and had excellent musicianship,” says Pratt. “It was like working with a pro when I first met him at age 13.”

Costanzo found the psychologically complex character and music challenging. “It was very difficult, but very fulfilling in a way I hadn’t yet encountered with the Broadway stuff,” he says. He’d discuss the Miles character with the director and with his parents on long car rides, trying to understand “what was going on psychologically with this kid [Miles] and then to inhabit that.” Costanzo says he approached the character as “more connected to me, as opposed to me going into that dark side of him.” He portrayed Miles as a “likable, happy kid” who descended into darker moments.

That role marked a shift in his career — from then on, he began focusing more on opera, drawn to the emotional intensity of its stories. “Everybody is yearning in opera for something, whether it’s power or love or reconciliation,” says Costanzo. Opera is not about the everyday, he says; “it’s about the day that changed everything. It’s about that one moment.” That intensity, he says, allows for a deeper connection with the audience. He also finds the opera experience more intimate than that of other musical performances, because opera houses use no microphones to amplify the singers. It’s “just a human voice that in its purest form is something that has the ability to penetrate,” he says.

It was during Costanzo’s work on The Turn of the Screw that colleagues suggested he might be a countertenor. At the time, Costanzo didn’t know what that was. But his voice had been changing very gradually, and he continued singing in the register he always had employed. There are “technical challenges” associated with cultivating the countertenor voice, he says, because it is farther from a singer’s speaking voice and uses a different set of muscles. If he didn’t sing as a countertenor, he would be a baritone. But, he says, “I don’t think my baritone would be nearly as interesting as my countertenor voice. As a baritone, I would be nothing special.”

Some teenage boys might have felt pressure to sing in the lower register after their voices changed. But Costanzo says he felt “zero pressure” to do so, crediting his parents, who raised him to disregard gender stereotypes. “I never felt that I should just be a man and stop using this high-pitched voice, even when the low one started to come in,” he wrote in Me, a small quarterly magazine that focuses on creative people. “I have never once felt emasculated even though I sing in a female register.”

As a teenager, Costanzo flourished professionally. He landed a small role in the Opera Extravaganza, a production with Luciano Pavarotti at Philadelphia’s Academy of Music, and performed as a soloist with several orchestras at the Kennedy Center and Carnegie Hall. He toured with The Sound of Music and appeared on Broadway in A Christmas Carol. He made his film debut in 1998, taking on the role of a boy who becomes fascinated with opera and becomes an opera singer in the Merchant Ivory film A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries, for which he received critical acclaim.

Surrounded by friends in New York who were actors and artists, Costanzo lived his art with his voice at the center. By the time he entered Princeton, he had performed in Europe and spoke French and Italian. Costanzo wanted to spend his college years seeing “the world through a larger prism” before moving full time into the narrower world of opera. He majored in music and earned a certificate in Italian, aiming to “get a firm grasp on the material which I [was] trying to convey.”

He took courses directly related to opera — music theory, Baroque opera, Italian, storytelling — and courses seemingly unrelated to his career. “I find everything applicable,” says Costanzo, who took a computer-programming class that he says strengthened his problem-solving skills: “The ways you think about solving intricate problems like [computer programming] are very similar to the way you might approach a challenging contemporary score.” A course taught by philosophy professor Peter Singer helped him delve into ethics, which get “very distorted [in opera], and you want to understand everybody’s perspective.”

Pratt had told Costanzo that if he enrolled at Princeton, Pratt would build things around him, “because even then he was an extraordinary talent.” Each year Costanzo performed a major countertenor role in a campus production: He was Nero in Monteverdi’s 17th-century opera The Coronation of Poppea and the young shepherd, Endimione, with whom the goddess Diana falls in love in Francesco Cavalli’s La Calisto. In his sophomore year, he performed in a concert of castrati repertoire with the University Orchestra. “I think he got a lot of mileage out of Princeton, but we sure got a lot of mileage out of him,” Pratt says. “He brought a level of vocal brilliance here that we hadn’t seen in a long time and maybe never will see again.”

The highlight of Costanzo’s Princeton work was his senior-thesis performance. To mount the production, Costanzo collaborated with world-renowned artists with whom he had worked as a teenager. Choreographer Karole Armitage, who has worked with classical musicians as well as pop stars like Michael Jackson and Madonna, directed the work; Oscar-winning director James Ivory, who had cast Costanzo in A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries, designed the Baroque-period costumes that were made by an atelier in Venice; Italian architect and designer Andrea Branzi created the abstract sets; and two professional dancers completed the small cast. To finance the thesis production and the documentary, Costanzo says, he raised funds from the University and from various departments: $35,000 for the production in Richardson and $82,000 for the film, Zefirino: The Voice of a Castrato, which was released in 2007. (Asked whether this was the largest amount provided for a senior thesis, University spokeswoman Cass Cliatt ’96 says officials are “not in a position to rank historical thesis-funding amounts.”) Costanzo kept track of a myriad of details, arranging dance and musical rehearsals in New York and at Princeton, figuring out how to get costumes safely from Venice to Princeton, shipping sets from Milan, and carving out hours to spend with his cast and supporters, who donated their time.

To collaborate with his co-writer, the scholar and dramaturge Stefano Paba, Costanzo traveled with him on a three-week cruise through Russia, Poland, and Estonia, on which Paba was lecturing about art. Communicating in Italian, they would work on the script half the day, then take a break when the ship docked to look at art, and then write more at night. Costanzo drafted the script in Italian and then translated it into English.

The Double Life of Zefirino opens with the castrato finishing a performance to rousing applause, then proceeds with a series of flashbacks and flash-forwards: his affair with a princess enamored by a performance, the suggestion of a relationship with a male painter, a confrontation. In the final scene, Zefirino deals with the painful memory of his castration and comes face-to-face with himself as a boy. Dressed in white, Zefirino and a boy actor hold hands as Zefirino sings a liturgical piece, recalling the origins of castrati in church choirs. During a moment of silence, the boy gently pulls a red handkerchief out of Zefirino’s sleeve. The boy holds it up and then lets it drop it to the floor, and Zefirino finishes the aria. Costanzo got a standing ovation from the audience at Richardson.

The documentary ensured that the story of Zefirino would not end with that ovation. One of Costanzo’s professors at Princeton, Gaetana Marrone-Puglia, had shared a CD of Costanzo’s singing with her husband, award-winning cinematographer Gerardo Puglia, who recalls being “spiritually moved by his voice.” With Marrone-Puglia as producer, the three decided to make a film based on the opera, shooting at rehearsals, at the final performance, and in Italy at the papal halls of the Vatican, the artists’ workshops in Venice, and the majestic San Carlo Theatre in Naples — places where the castrati tradition began. The result: a 23-minute documentary that was selected for the Cannes Film Festival in 2007 and won a Director’s Choice Award at the Black Maria International Film Festival in 2007.

Within the last few years, Costanzo’s career as an opera singer has taken off. He lives a disciplined life in a sleek Manhattan apartment owned by his parents, getting to bed by 10 or 11 p.m. for weeks before major performances, eschewing all alcohol save for the occasional glass of wine (and never within the week before he performs); maintaining a diet meant to keep his voice in top form. The anatomy of his instrument, the voice, is never far from his mind; over his bed hangs a large drawing of the head and neck. For inspiration, he attends dance performances and art exhibits as well as other operas. He calls himself a “culture addict”: “I’m always looking for that one second — and it’s usually not more than a second — of something moving you. I give myself as many opportunities as possible to experience it ... so maybe I’ll have a better chance at creating it.”

He’s had his share of doubts and worries, most notably in 2007, when he was diagnosed with thyroid cancer and required surgery to remove the thyroid, which sits atop nerves that control vocal functions. His longtime voice teacher, Joan Patenaude-Yarnell, says Costanzo had only one low moment — when, a few days before surgery, he chose to sing for her the somber Italian arias, “Let Me Die” and “What Will I Do Without My Euridice?” about a man who sings over his dead wife’s body. “He sang it like a man going to the gallows. I’ve never heard such intensity in my life,” the teacher recalls. All went well in two surgeries, and Costanzo is cancer-free — with a voice, Patenaude-Yarnell says, that “came back more beautiful than ever.”

For the past two summers, Glimmerglass, a summer opera festival based in New York, has been grooming Costanzo for a title role, and in the summer he will perform the role of Tolomeo in Handel’s opera by the same name. His character is a hero-lover who considers killing himself because he can’t bear the idea of losing the woman he loves. Last summer, Glimmerglass awarded Costanzo the Richard F. Gold Career Grant, for a young artist who demonstrates potential for an important career.

In December Costanzo debuted with the Cleveland Orchestra, singing Handel’s Messiah, and returned to Carnegie Hall for performances of Messiah with Musica Sacra. Next month he makes his New York City Opera debut as Armindo in Handel’s Partenope, and in May appears with the New York Philharmonic as Prince Go-Go in Le Grand Macabre by György Ligeti. Later — the date is not set — he will appear at the Metropolitan Opera.

Costanzo has played heroes, lovers, good guys, and villains. As the treacherous Polinesso in Handel’s opera Ariodante at Juilliard Opera last November, he embodied the character who is rejected by the princess and devises a scheme to ruin his rival, Ariodante. He entered the stage menacingly, projecting tension (the character, Costanzo says, is “a real schmuck,” willing to roll over anyone for power), and later became flirty and sensual as his character seduced a woman and drew her into his web of deception. In its review, The New York Times called Costanzo “an intense, engaging countertenor.”

The singer admits that he gets nervous before each performance, but when he’s at his best, he feels like he’s “floating.” “It’s important to let go of everything you’ve prepared and just perform when you walk on stage,” he says.

That’s what he did when he walked alone onto the stage of the Met last spring to perform in the finals of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions and filled the 4,000-seat hall with his voice and presence. He performed two arias. One was complicated and fast, with strings of moving notes; it told the story of a man torn between his love for a woman and his desire for revenge against her family. In the second, he sang as a man forced to drink poison to prove his love for his wife. Near the end, Costanzo “died” as the poison took effect, and the music faded out.

When he finished singing, there was a moment of silence before the audience erupted into huge applause and cries of “Bravo!”

“I think every singer dreams of this moment,” says Costanzo, seemingly unable to believe it had taken place. “That actually happened.”

Katherine Federici Greenwood is an associate editor at PAW.

No responses yet