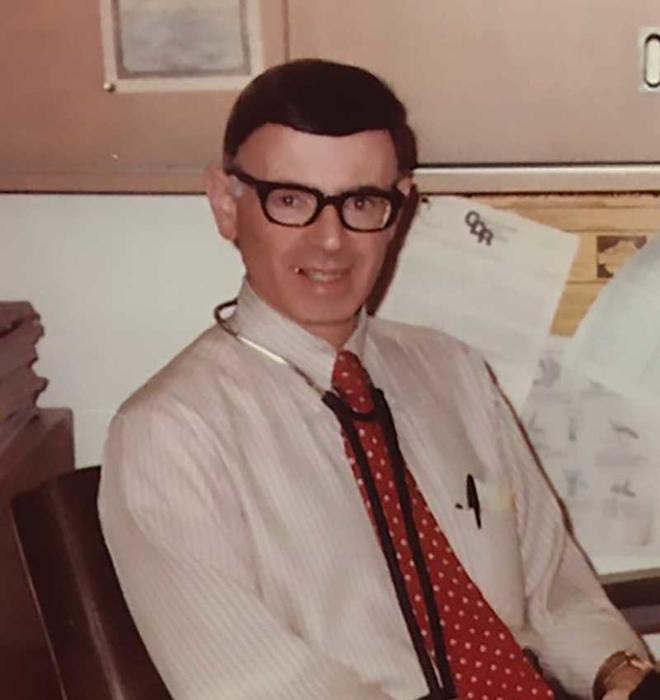

April 28, 1938 – January 21, 2021

From the start, he was a shooting star, a violinist with talent beyond his years, an accomplished writer, a kind and generous soul. What Avron J. Maletzky ’59 was not was a social animal.

He was quiet and shy, seemingly happy hiking alone on long treks into the Cascade mountains of the Pacific Northwest. He lived by himself for most of his life, yet sprinkled through the Seattle area, there are families in which a mere mention of “Dr. Maletzky” summons tears of gratitude, even decades after he cared for their seriously ailing children.

In the mid-1980s, when Maureen O’Reilly’s infant son Devin started to breathe 200 times a minute, she knew that the heart murmur he’d been born with had become much more serious. At the emergency room, Maletzky appeared and instantly connected with her son.

The pediatric cardiologist “looked ridiculous,” O’Reilly says. “He wore a wig that looked like a helmet. But he was a total star with our son, totally available, so shy with adults, but so much more comfortable relating to a child.” During a long hospital stay with her son, O’Reilly would sometimes wake in the middle of the night to see Maletzky with his stethoscope, listening to her son’s heart, “for a long, long time, 10 minutes, just silently listening. The children were fascinated by his calm. He and the child were a team.”

Dr. Barrett Maletzky, Av’s younger brother, says his sibling was a superb physician who “handled the toughest of cases. And he was bizarre at times, had no close friends. He bought a beautiful home overlooking Elliott Bay, but there was no furniture in most of it.”

Av was 16, still in high school in Schenectady, New York, when he won the Voice of Democracy scriptwriting contest, sponsored by the nation’s broadcasters. He received $500, a television set, a trophy, and a trip to Washington, where he met President Dwight Eisenhower at the White House.

At Princeton in the 1950s, during a time of overt discrimination by eating clubs against Jewish students, Maletzky, along with fellow Jews and others who had been excluded in the bicker process, found refuge at Wilson Lodge, a section of Commons that the University established for those upperclassmen.

Maletzky found his way into the life of the broader campus through music. He played the violin in the Triangle Show and was concertmaster of the University Orchestra and the Savoyard.

After college and medical school, he spent two years as a virology researcher for the U.S. Public Health Service in Seattle, and stayed. As hard as it was for him to speak up in groups of people, he was eloquent on his instrument, playing in the Cascade Symphony and becoming concertmaster of Orchestra Seattle and a Gilbert and Sullivan light opera ensemble.

The Cascades were Maletzky’s passion and solace. He bushwhacked his way through the backcountry, sometimes on snowshoes, sometimes wielding an ice axe, says Fritz Klein, a fellow violinist and hiker.

“He was called to the mountains,” says Gene Duvernoy, who ran a conservation organization and occasionally hiked with Maletzky. “He knew routes no one else knew. He even built trails where he thought they should be.”

“He was an eccentric, which a lot of people were in the Pacific Northwest before Microsoft,” Duvernoy says. “You would almost think he was incapable of talking sometimes, but in the mountains, he would talk about things he was passionate about” — the land, music, his patients.

And he was magical with children. “He could adopt the thinking of a child,” Duvernoy says. “He was quiet, really quiet, a modest, self-effacing hero.”

Marc Fisher ’80 is senior editor at The Washington Post and chair of the PAW board.

No responses yet