May 28, 1931 – July 23, 2015

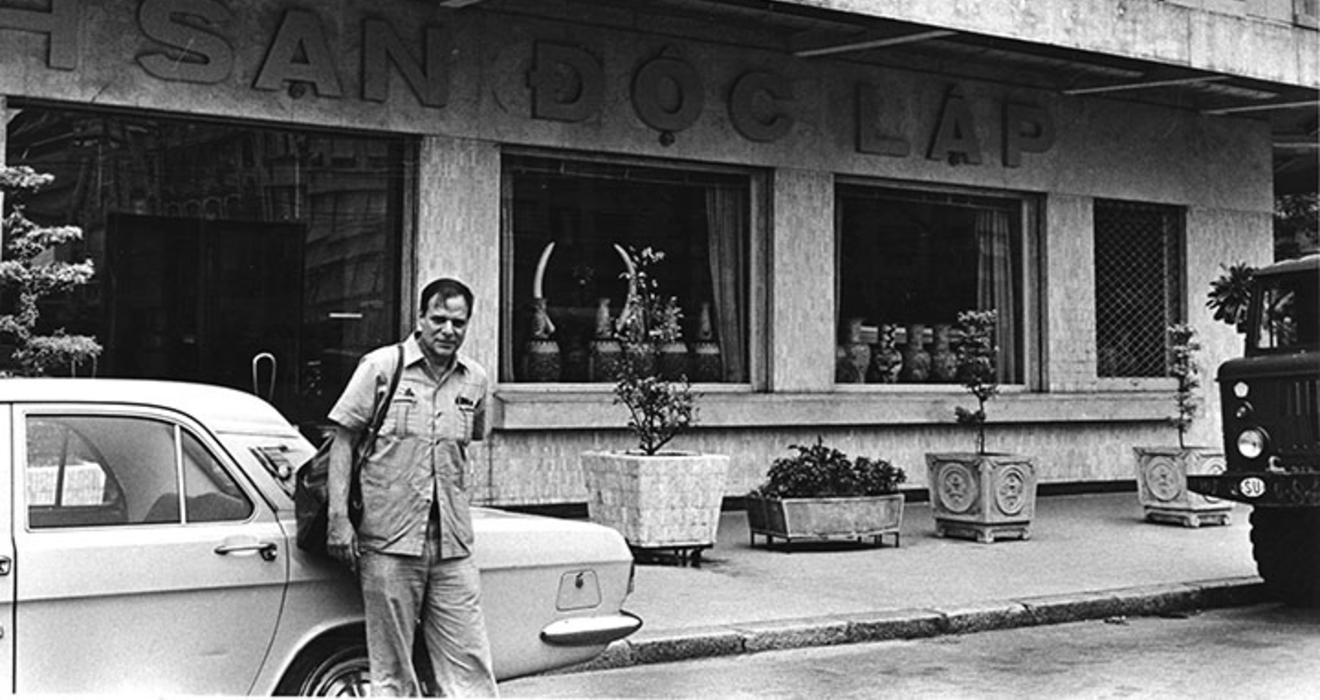

Don Oberdorfer — he eschewed using his full name as a byline because it was just too long — was nobody’s stereotype of a journalist. He was not cocky, flashy, superficial, or speedy. Friends described him as sober and contemplative, rumply and kind. Over four decades at The Washington Post, The Charlotte Observer,and the Saturday Evening Post, he was a phenomenon that today is very much in danger of fading away entirely: a journalist who was an expert in his own right. He cultivated and maintained sources for decades, specialized in a small handful of topics, and bridged the worlds of journalism and academia, becoming something of a colleague to the scholars and government officials who shared his fascinations with Korea, Vietnam, the Cold War, and the art of diplomacy.

Oberdorfer spent the bulk of his career at The Washington Post, where he covered the White House, the State Department, and foreign policy, and served as the paper’s Tokyo bureau chief. Rare is the reporter whose notebooks are worth saving, let alone becoming part of Princeton’s Mudd Manuscript Library, where 17 boxes of Oberdorfer’s notes chronicle his time as what legendary Post editor Ben Bradlee called “a foreign-affairs expert who could and did peg even with the very best foreign-affairs experts.”

He covered superpower summits and ministerial meetings, conducting long, detailed interviews with the principals — presidents, secretaries of state and defense, foreign ministers, intelligence sources. He was a master of the art of playing one side to win over the other; for Oberdorfer’s book on the end of the Cold War, The Turn, Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze gave him the only book interview he ever provided while in that position. Oberdorfer’s book on the Tet offensive, the turning point in the Vietnam War, remained in print for decades, becoming a standard college text.

Rare is the reporter whose notebooks are worth saving, let alone becoming part of Princeton’s Mudd Manuscript Library.

Oberdorfer grew up in Atlanta and landed at Princeton because a good friend in high school was eager to go there. Oberdorfer had “no idea what I was getting into,” he told C-SPAN interviewer Brian Lamb. “I was scared to death. All the people around me had come from, I thought, the best prep schools in the United States.”

He flourished. He’d known since third grade that he wanted to be a newspaperman, and he went from editor of a neighborhood newspaper in grade school to editor of his high school paper to editor of The Daily Princetonian and on, after a stint in the Army in Korea, to the paper in Charlotte, N.C.

In 1995, Oberdorfer, who returned to Princeton three times to teach, wrote the coffee-table book commemorating the University’s 250th birthday. In Princeton University: The First 250 Years, Oberdorfer called Princeton “a national institution before there was a nation.”

On Oberdorfer’s first day at the Post, in 1968, Bradlee summoned him to breakfast and asked how he’d feel about covering any of the presidential candidates: George Wallace, Hubert Humphrey, and Richard Nixon. “Fine,” Oberdorfer responded in each case. Several of the Post’s national political reporters couldn’t stand Nixon, and Bradlee was determined to have a reporter without pre-fixed notions on the beat. Later that day, Bradlee put Oberdorfer on the Nixon campaign. “Fine,” the reporter said.

Marc Fisher ’80 is senior editor at The Washington Post.

1 Response

Jan Lodal *67

9 Years AgoA Model Reporter

I met Don Oberdorfer ’52 (“Lives Lived and Lost,” Feb. 3) as a young deputy to Henry Kissinger on Richard Nixon’s National Security Council staff, where I was responsible for arms control. I sat in on all the NSC and summit meetings of that era. Don and Mike Getler of The Washington Post were my main press contacts. I always felt that I learned more from them than they did from me! Don was a great reporter, a model for generations to come. He never betrayed a confidence or stretched the truth, while always getting the story.