People often used the word “plainspoken” to describe the poet Galway Kinnell ’48, and, indeed, many of his poems were quite approachable. “When one has lived a long time alone / one refrains from swatting the fly” is how one of his better-known poems begins. But Kinnell also was prone to digging into old, fat dictionaries to rescue words like “plouters,” “sloom,” and “noggles.” Asked by an interviewer why he used such words, Kinnell said, “I hate losing them, so I use them. But I use them only when they pay their way.”

Kinnell died in October, of leukemia, but in August attended a celebration of his work at the Vermont Statehouse. Too weak to read, he listened to his granddaughter recite one of his poems from memory.

Kinnell grew up in Pawtucket, R.I., and joked that the stultifying nature of the place drove him to verse. At Princeton, he eschewed the poetry classes taught by R.P. Blackmur and John Berryman, thinking his work wasn’t yet ready for scrutiny. But after a graduation delayed by a World War II stint in the Navy, he went on to get a master’s degree at the University of Rochester and to peripatetically write, teach, and lecture at American and French universities and even in Tehran. He eventually settled down at New York University, commuting to a farmhouse in Sheffield, Vt. Coming of poetic age in the wake of modernism, Kinnell strived to find a less austere, more personal tone than the likes of Eliot or Pound. His breakthrough work was “The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ into the New World” (1959–60), a Whitmanesque tour of downtown Manhattan that captured the city’s ethnic variety, in all its quotidian tumult, while invoking the Holocaust as a persistent shadow.

He supported the movement against the Vietnam War and the struggle for civil rights in the American South, landing in jail after helping to register black voters in Louisiana. Laments about inhumanity remained a theme of his work from the 1960s into the 2000s. In “When the Towers Fell,” he tried to get inside the minds of those who died, trapped on high floors, on 9/11.

Kinnell won the Pulitzer Prize in 1983, and became Vermont’s poet laureate — the first since Robert Frost — in 1989, two of innumerable artistic honors. He wrote often about his children, Fergus and Maud, and also about the natural world; in some of his most popular poems, the barrier between human and nonhuman all but dissolves.

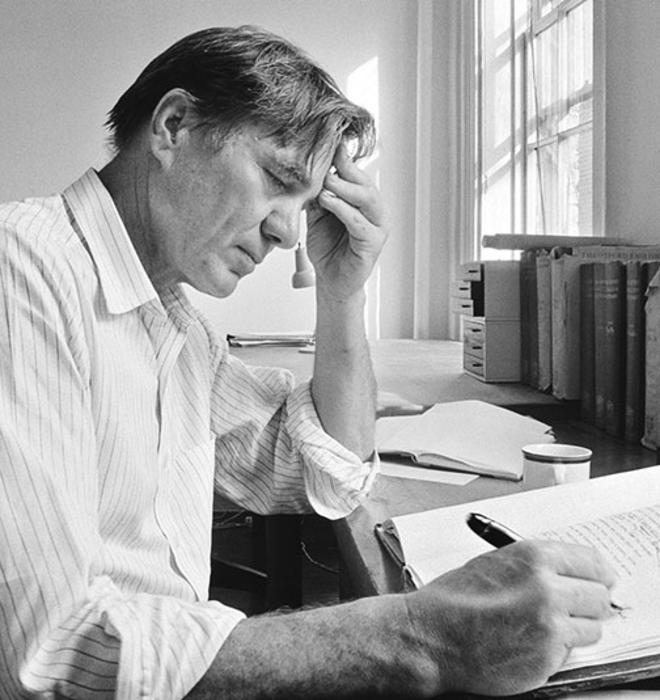

He was a charismatic reader, with a rich voice and striking good looks, a combination that for some poets has proved self-destructive. But Kinnell wrote against the notion that poets could do whatever they liked in their personal lives if they created great art. “He was a decent man, who believed in decency,” says classmate Edmund Keeley, who headed Princeton’s creative writing program for 16 years. Philip Levine, a former U.S. poet laureate, described Kinnell in August to The Burlington Free Press as “a real American ... the kind of person that this country created and hopefully still creates. People from nowhere somehow invent themselves. They say, ‘I’m gonna be a poet, and I’m gonna be a good person.’” And Kinnell was.

Christopher Shea ’91 is a contributing writer for The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Kinnell reads his 2000 poem “Saint Francis and the Sow.” (Links to PoetryFoundation.org)

No responses yet