DEC. 27, 1930–MARCH 6, 2016

Few American diplomats played so important a role in 1970s foreign policy as Hal Saunders, assigned to negotiate peace in the war-torn Middle East. Among his many achievements: helping to win the release of the American hostages in Iran in 1981, whom he accompanied home.

Son of an architectural engineer in Philadelphia, Saunders credited Princeton’s American Civilization program with exposing him to interdisciplinary thought, later invaluable in navigating the complex waters of foreign affairs. “The idea of Princeton in the nation’s service was seared in my soul,” he said.

After earning a Ph.D. from Yale, Saunders joined the CIA during the height of Eisenhower-era Cold War espionage. Then, at the National Security Council in the Kennedy years, he worked 10 or 12 hours a day — a schedule that later seemed light.

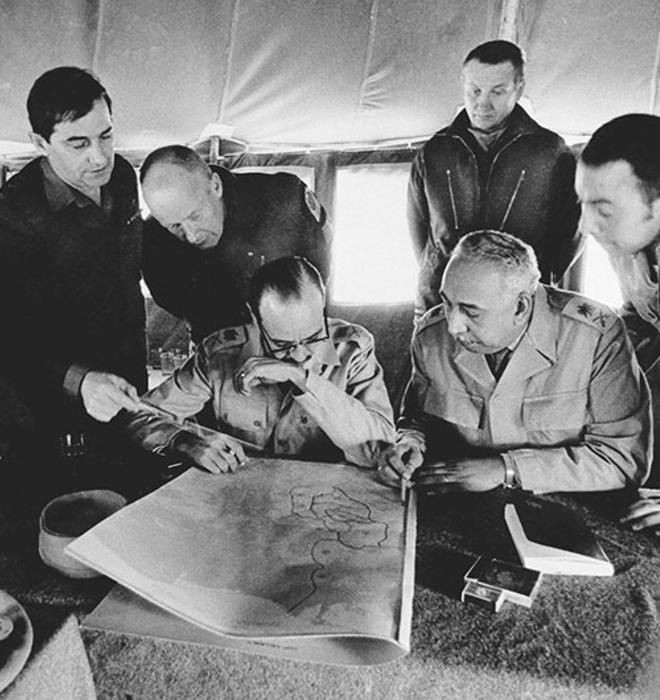

The 1967 Arab-Israeli war found him constantly on a hotline to the Soviet Union. A bloody sequel to this conflict in 1973, often called the Yom Kippur War, led Saunders to undertake a feverish round of shuttle diplomacy alongside Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, with whom he spent much of nine months on airplane trips around the world.

Peace-loving Saunders and the hard-line Kissinger sometimes butted heads about policy. Once, on a turbulent flight, Kissinger fell against a copy machine. “Careful, Henry,” Saunders said. “One of you is enough.”

In a 1993 oral history, he recalled, “I was asking myself how much longer could I physically stand the pace.” But eventually he helped achieve two disengagement pacts in 1974: between Israel and Egypt, and Israel and Syria.

He moved to the State Department in 1974. At the historic 1978 summit at Camp David that brought together Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, and U.S. President Jimmy Carter, Saunders — by then assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern and South Asian affairs — was responsible for the 22 drafts that led to a peace accord after nearly two weeks of negotiations.

“I was immensely gratified by what had been achieved,” Saunders later recalled, although he worried that the agreement carried great political hazards for Sadat —assassinated three years later.

When his first wife, Barbara, died in 1973 — on the day the Yom Kippur War began — Saunders was left to raise two children alone. “He did a very good job,” says daughter Cathy Saunders *02, although it was not easy for the kids when “he had to go two weeks with Kissinger and then actually stayed six weeks. His work was his life.”

Incapable of retiring, the man credited with coining the term “peace process” then developed the Sustained Dialogue approach to conflict resolution, an effort defined by its practitioners as “listening deeply enough to be changed by what you learn.” Saunders applied it successfully, for example, to the peace-building process in Tajikistan between 1993 and 2005, requiring 35 more trips abroad.

Then, starting with Princeton, he founded the Sustained Dialogue Campus Network to help students discuss race and other challenging issues. Saunders oversaw its growth to 53 campuses in nine countries until cancer finally slowed him.

Five days before his death, Saunders was dictating a historical memoir, determined to get the facts right. “Hal’s efforts helped start a peace process,” Kissinger wrote to his widow, Carol. “The nation benefited from his vision and dedication.”

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 is the author of seven books, including the award-winning Princeton: America’s Campus and The Brandywine: An Intimate Portrait.

No responses yet