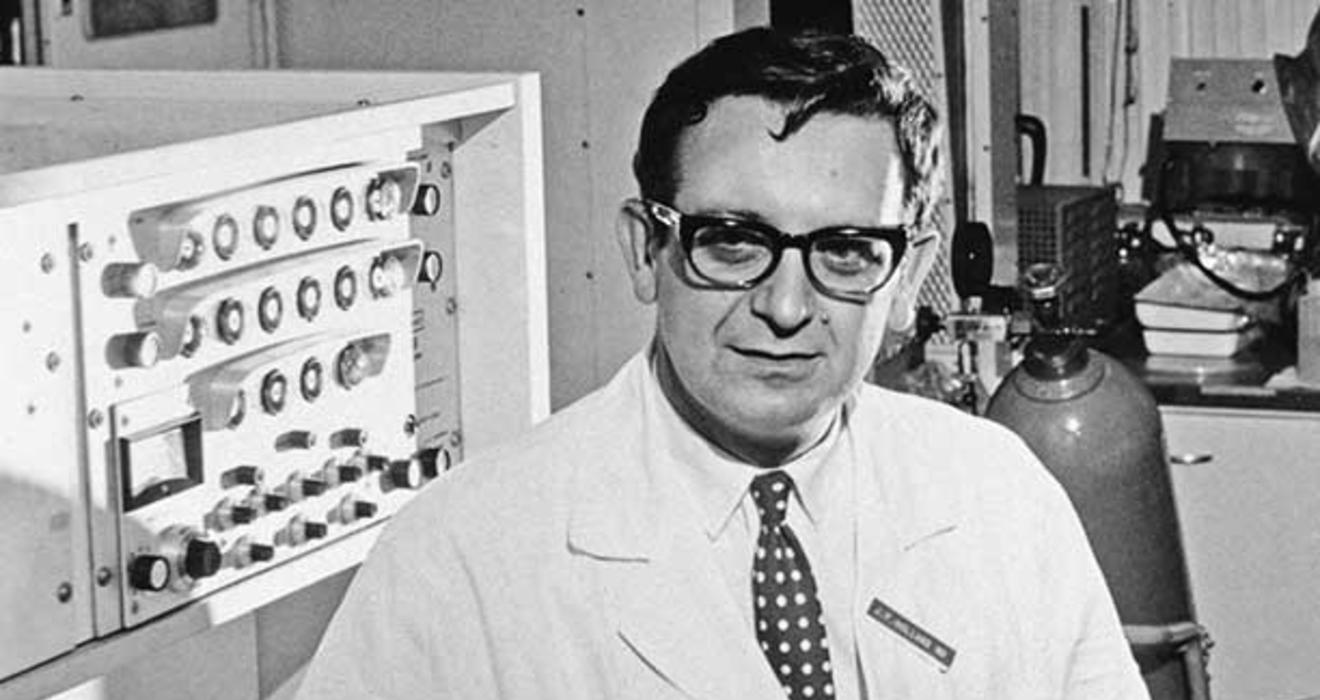

May 16, 1925 • March 22, 2018

JAMES HOLLAND ’45 spent his life fighting cancer — and sometimes, other cancer doctors.

In the 1950s, when Holland began his pioneering work on chemotherapy, acute childhood leukemia was almost always fatal. As Holland’s research team methodically tested high-dose drug combinations in rigorous clinical trials, other doctors accused them of conducting unethical experiments on human guinea pigs.

But their patients began recovering. Today, acute lymphocytic leukemia in children has a five-year survival rate of more than 85 percent.

Holland “brought about a sea change in thinking about the disease,” says Jerome Yates, a colleague and lifelong friend. “He really believed that the problem could be solved, when the establishment in medicine thought that we were blowing in the wind.”

In such groundbreaking research, “nobody else understands exactly why you’re doing it, and every failure is viewed as proof that you were wrong in the first place,” says Holland’s son Steven M. Holland, himself a physician-researcher. “It takes a special guy to power through that.”

Always precocious, Holland was carrying a briefcase to school by fourth grade, says his daughter Diane L. Holland. At Princeton, where he enrolled at 16, a biology class set him on the path to medical school. A post-residency scheduling conflict changed his training plans, turning his attention to the emerging discipline of oncology.

Years later, he said he stayed in the field because “it was the frontier,” Diane Holland recalls. “Nobody had really been there before.”

A father of six, Holland drove his children to school every morning and ate dinner with them each night. But he also worked long hours, returning to his patients at the cancer hospital in Buffalo, N.Y., once his own children were in bed.

“His commitment to his patients and to the science behind making them better was a palpable part of everyday life,” says his son Steven.

Holland shared that commitment with his wife of 61 years, psychiatrist Jimmie Holland, who pioneered the field of psycho-oncology, the treatment of cancer patients’ emotional suffering. She died in December 2017, three months before her husband.

James Holland, who joined New York City’s Mount Sinai hospital and medical school in 1973, continued seeing patients and conducting cancer research there until weeks before his death at 92. “Time is always of the essence in any of this,” Holland told author Tim Wendel, whose 2018 book Cancer Crossings recounts the battle against childhood leukemia. “If I can get a few more years, I sincerely believe I can help find a cure for other cancers. It’s always a race.”

Although the cancer treatments Holland helped develop constitute the best known part of his legacy, equally important was his work as educator and scientist, Yates says: Holland trained a new generation of activist cancer doctors, and the leukemia trials he oversaw — with biostatisticians parsing the effectiveness of competing treatments — helped bring a new rigor to clinical medicine.

“He always was pressing ahead,” says Diane Holland. “He was driven by a passion, and look what it’s done for the world.”

Deborah Yaffe is a freelance writer based in Princeton Junction, N.J.

No responses yet