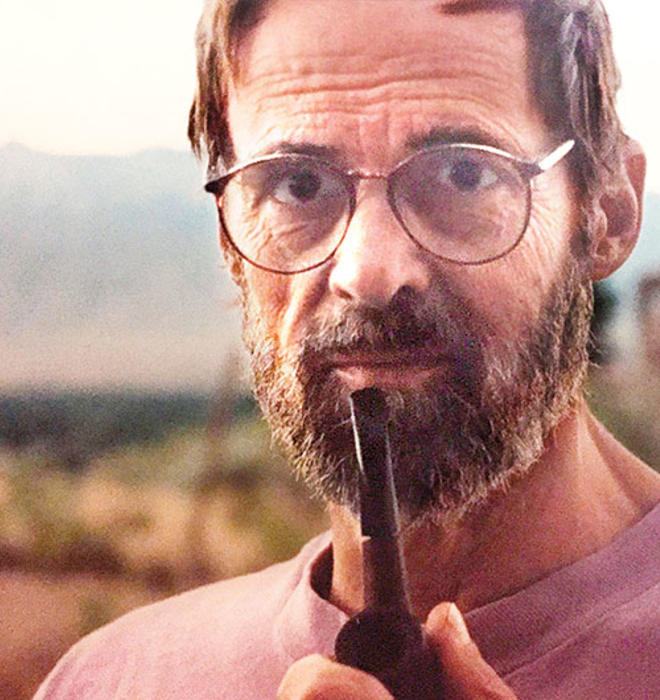

JAN. 24, 1936–FEB. 10, 2016

In 1974, James K. “Jake” Page ’58 made his first trip to the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona with his wife, Susanne, an accomplished photographer whom tribal leaders had invited to create a book about the Hopi community. Page, a freelance journalist, was to write the accompanying text.

The two visited a compact, dimly lit home in the Second Mesa villages, and Page took a seat on a bed that doubled as the living room couch. “All of a sudden there was a terrible scream,” Susanne recalls. “He’d sat on their cat!”

Page quickly made amends for his inauspicious landing, and in the days — and decades — that followed, he built friendships with many in the Hopi communities, chronicling traditions and customs rarely shared with outsiders. “He never took a notepad and never asked questions of people,” Susanne says. “He just let them explain what they wanted to explain.”

Page later wrote that his Hopi friends had enriched his life “in ways that one does not count.” He repaid that generosity with carefully crafted writing that covered contemporary life in the pueblos; history, including an ambitious and widely praised 20,000-year survey of American Indian cultures; and fiction, in a series of witty detective novels.

The novels were inspired by the real-life theft of Hopi religious material, a story Page initially pitched to his magazine contacts. Editors turned him down, fearing that his reporting would cast museums in a negative light or upset gallery owners who placed ads in their pages. So Page turned to fiction, starting what would become a series of five books featuring Mo Bowdre, a blind sculptor and amateur sleuth based in Santa Fe. “Why he is blind I will never know,” Page told critic Ray B. Browne in a 2003 interview, “but he is, and it is an interesting challenge.”

Page’s fascination with Indian cultures filled the latter chapters of a long and varied career that began in book publishing and continued with editorial jobs at Natural History and Smithsonian magazines. He spread his wings midway through his career when he became a full-time freelancer — a “Swiss Army knife of a writer,” in Susanne’s words, which is an apt description since he once co-wrote a seven-page feature about that very object, “the world’s most portable tool kit.” He wrote about space exploration, the inner workings of the U.S. Postal Service, clear-cutting in the Amazon, a search for the best chicken-fried steak in Texas, and scores of other topics that stirred his curiosity.

Page was the author or co-author of 49 books; the last, a biography of Hollywood makeup artist Michael Westmore, is due out in March. His most frequent collaborator other than Susanne was his Princeton roommate, David Leeming ’58, a retired English professor and scholar of mythology.

Leeming and Page wrote four books together, an experience that Leeming describes as “absolutely pure fun.” The two men would sit in the same room, each at a computer, and share ideas as they wrote their drafts. It was as if they were still undergrads at Renwick’s, the Nassau Street restaurant where they would meet most nights to discuss Henry Adams and Henry David Thoreau, the subjects of their senior theses.

Leeming admired Page’s confidence as a writer, which never strayed toward arrogance or pedantry and served him well as he tackled new subjects. “Jake was not intimidated by anything,” he says. “If you had asked him to write a history of life or a history of the world, he would have done it.”

Brett Tomlinson is PAW’s digital and sports editor.

No responses yet