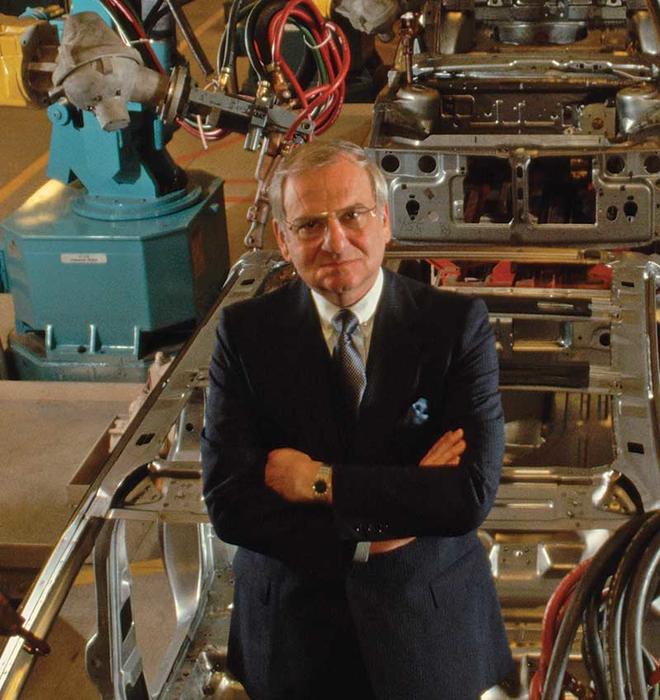

When Chrysler president Lee Iacocca *46 was promoted to chairman and CEO in 1979, he brought five of the company’s leaders to his home to share the news. The carmaker had 140,000 employees, rapidly mounting debts, and a tenuous bid for assistance from the federal government. But Jerry Greenwald ’57, executive vice president for finance at the time, recalls Iacocca’s tone as unfailingly optimistic: “He looked around and said, ‘Well, you guys always wanted to run a company, didn’t you?’ ”

For much of the early 1980s, Chrysler’s trajectory validated Iacocca’s positive outlook. Greenwald compares it to what athletes call being “in a zone” — when every pass reaches its target, every shot hits the mark, and not even the players can explain why.

The management team would continually encounter challenges that could well mean the end of Chrysler. Each time, they resolved the problem. “It would happen day after day after day,” Greenwald says, “and because we succeeded every time, we built this [attitude] — you could call it a cocky attitude — that no matter what happened, we were going to fix it.”

Iacocca — part engineer, part pitchman — would have slumps later in his tenure, but he remained one of the most admired executives in America. Chrysler returned to profitability, and in 1983, it finished repaying the loans from its federal bailout. In 1984, Iacocca’s self-titled autobiography sold more copies than any other hardcover book that year. A son of Italian immigrants, he led the fundraising for a major restoration of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. He was so popular that Democrats tried to recruit him to run for president, even though he was a registered Republican.

For Iacocca, the Chrysler years were vindication following his ouster from Ford, where he’d started as an engineer in 1946 after receiving his master’s degree in mechanical engineering from Princeton. He climbed to the role of president before falling out of favor with then-CEO Henry Ford II.

At Ford, Iacocca left engineering relatively early on and moved into sales, where his mastery of marketing and communication put him on a path to the executive suite. “He could give a speech in front of any audience — might be union guys, the Chinese government, Wall Street bankers, car dealers — it almost didn’t matter,” Greenwald says. “He could charm your socks off, and he could get you to do things you didn’t think you could do.”

Iacocca also understood what his customers valued. Baron Bates ’56, Chrysler’s vice president of public relations from 1979 to 1990, remembers an episode in 1987 when the company faced federal fraud charges for disconnecting odometers for test drives and, in some cases, selling damaged used cars as new. Lawyers advised that the executives say nothing, fearing that any admission would hurt the company at trial.

Iacocca brushed the lawyers aside and scheduled a press conference. With characteristic bluntness, he called disconnecting odometers “dumb” and selling damaged cars “stupid.” He apologized to those who’d bought the affected cars and promised to make things right. Chrysler eventually paid a $16 million settlement and extended warranties for an estimated cost of nearly $10 million more, but Iacocca emerged with his reputation intact.

Brett Tomlinson is managing editor of PAW.

OCT. 15, 1924 | JULY 2, 2019

No responses yet