Dec. 9, 1919 – Feb. 21, 2015

To those who love the English language, Welsh has special appeal. The oldest language in Britain, it binds us to our Celtic past, to words and sounds mostly wiped out of the British Isles by successive invasions of Vikings, Romans, Angles, Saxons, Danes, and Normans — and then by the incursions of the New World and new media. Our affection for Welsh may be enhanced by the language’s stubborn refusal to go extinct.

But to Meredydd Evans *55, Welsh (or, as he would say, Cymraeg) was neither abstract curiosity nor source of sentimental interest. It was his life.

He was born in 1919 at Llanegryn in Merionethshire and brought up in Tanygrisiau in Blaenau Ffestiniog, near the slate quarry where his father worked. His mother bore 11 children; it was from her that he inherited his musical gift and his devotion to Welsh culture. “She sang all the time around the house, and in the evening — around the table or the fire,” he once told a documentarian. “She sang because she wanted to sing, or she wanted to calm a child.”

Hers was what he called “that familiar, unaccompanied voice” of true folk singing — “one person, singing as naturally as a bird.” Like her, Evans expressed himself in Welsh; in his case the “unaccompanied voice” was a light tenor, at once clear and enveloping, haunting and reassuring.

Evans inherited his musical gift and his devotion to Welsh culture from his mother. “She sang all the time around the house,” he once told a documentarian.

Evans began singing seriously at the University College of North Wales, Bangor, which he attended after having been exempted from military service as a conscientious objector. He and two friends formed the close-harmony trio Triawd y Coleg (“The College Threesome”).

He met his wife, the American opera singer Phyllis Kinney, in Britain in 1948. The couple married, moved to Princeton (where Evans enrolled as a graduate student in philosophy), and had a daughter. There, and “out of the blue,” Evans received a letter from Moe Asch, of Smithsonian Folkways, who was curious to hear Welsh folk songs. An album was recorded; Welsh Folk-Songs by Meredydd Evans went on to be named one of the year’s dozen best folk records by The New York Times.

From 1955 to 1960, Evans taught at Boston University. But he longed for Wales — and not just for himself.

“If you want to be part of Dad’s life,” his daughter Eluned said in a 2014 interview, “you must speak Welsh.” The family returned, and all three Evanses immersed themselves in the language.

“All my life I’ve been unsure of which direction to go,” Evans mused in 2014. “Philosophy held a great appeal — sharing and trying to understand. On the other hand, I was drawn to the business of entertainment.”

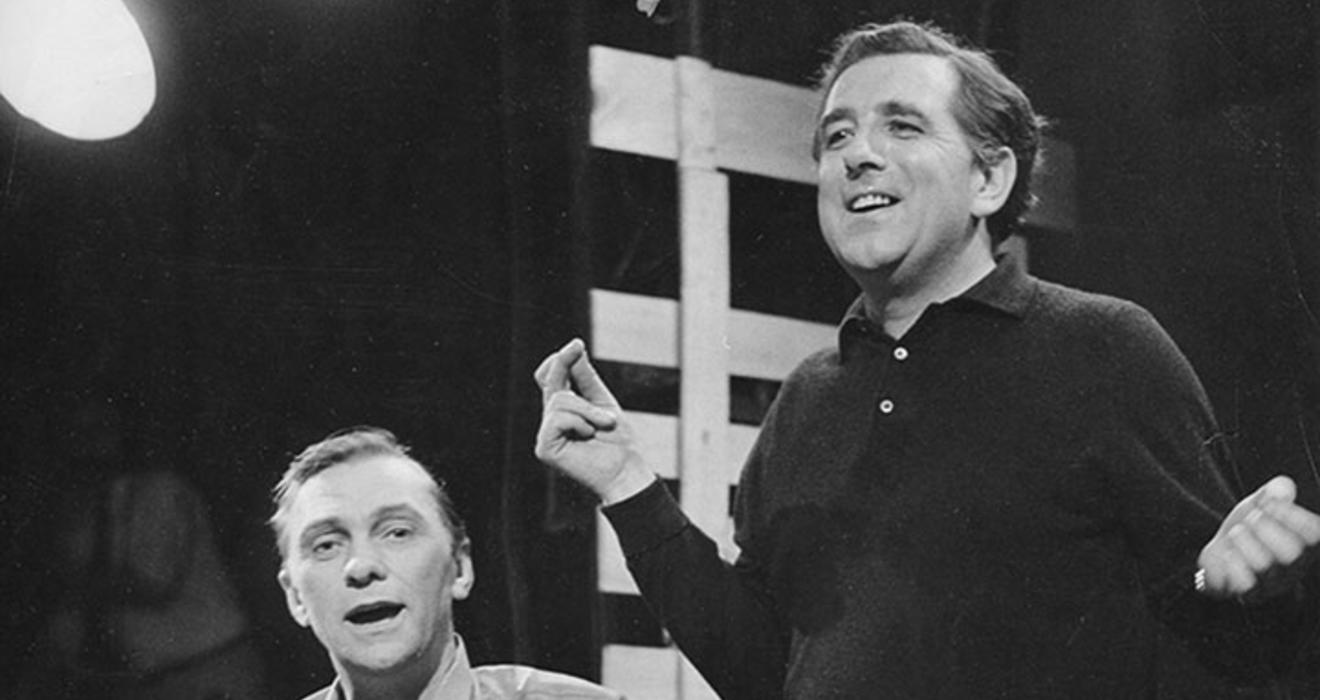

Evans became a university lecturer in philosophy, but then, from 1963 to 1973, was head of Light Entertainment at the new BBC Wales. He produced popular television programs, including Fo a Fe, in which a beery, loquacious, Marxist collier from South Wales came into weekly conflict with a sanctimonious, organ-playing, Liberal deacon from the North.

Evans put his career in jeopardy with acts of civil disobedience and as a senior member of the Welsh Language Society (Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg). In 1979, he and two academic colleagues were found guilty of switching off a television transmitter to protest the government’s delay in establishing a Welsh TV channel. Welsh speakers, Evans believed, had a moral right to full service in their own language, and a right to civil disobedience. The channel, S4C, was launched in 1982.

Evans and his wife settled in Cwmystwyth, a small village in the hills of Ceredigion, near Aberystwyth. Until just a few months before his death, Evans worked daily in his study, lined on all four walls with books and research files and journals. “I wonder sometimes what drives him,” mused Eluned, when Evans was 94. “I feel that he wants to share as much of his knowledge as he can before he departs.”

Journalist Constance Hale ’79 is the author of Wired Style, Sin and Syntax, andVex, Hex, Smash, Smooch.

No responses yet