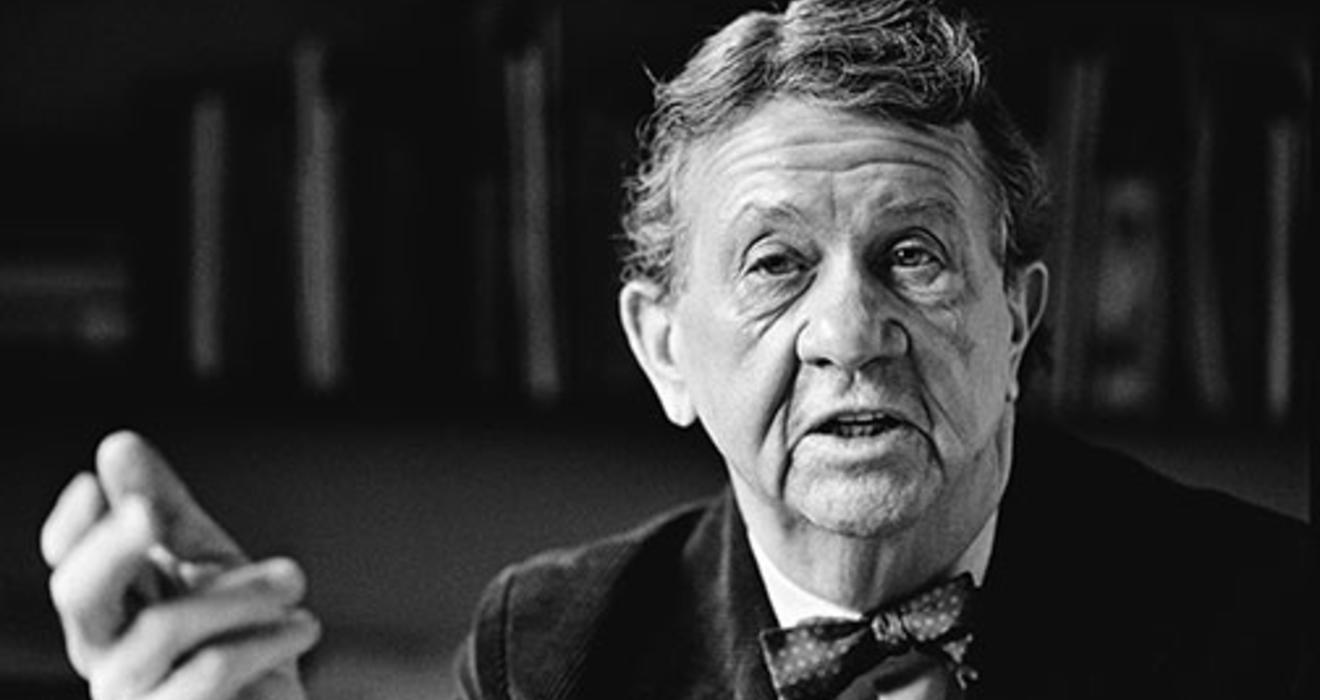

Oct. 12, 1915 – Nov. 8, 2013

Eagle Scout, chairman of the Prince, Rhodes scholar, U.S. Marine in the Pacific theater during World War II; later, a journalist at Time and The New York Times, political adviser, and longtime professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. The record of Penn Kimball ’37 was unassailable but for the asterisk: In 1946, he was falsely, and secretly, deemed a security risk by investigators at the State Department and the FBI.

The dossier against him fattened in the 1950s after investigations by the CIA (which, ironically, may have been thinking of recruiting him). He remained ignorant of the files’ contents for decades, but his quest to clear his name, beginning in 1977, defined the last chapter of his professional life. In school, “we do not learn, nor should we accept, that nameless moles can brand us disloyal for our lifetime,” he wrote in his 1983 book about his travails, The File.

Kimball readily noted that others suffered more than he from anti-Communist witch hunts, but the mainstream nature of his beliefs — he was a down-the-line New Deal Democrat — made the sub rosa judgments about him especially Kafkaesque. He never knew what the files cost him, professionally, but in 1962, for instance, an expected appointment to the Federal Communications Commission inexplicably evaporated.

The saga began in 1945, when, transitioning to civilian life, Kimball took the Foreign Service exam. He scored well and seemed on track to being offered a post in Saigon, but took a job with Time instead. Security investigators’ suspicions had been kindled, however, by his having worked, pre-war, for PM, a left-leaning newspaper, and by comments from residents of his very conservative hometown, New Britain, Conn.

Ignoring accolades, agents played up the views of one New Britainite who called Kimball “one of those young fellows who have received too much education and gone communist or socialist.” They scribbled down the testimony of a Time employee who said Kimball “aligned himself with the communist element” in the magazine’s union. Kimball learned something was amiss in 1948 when, between jobs, he queried if a Foreign Service position was still available. It wasn’t, and he couldn’t extract an explanation of what the investigation had turned up.

Kimball was professionally restless: He quit Time for The New Republic; he helped start the cultural television show Omnibus; and he assisted on political campaigns both successful (Connecticut Gov. Chester Bowles) and not (New York Gov. Averell Harriman’s re-election bid).

In the mid-’70s, with the government promising new transparency, Kimball finally decided to investigate the blotch on his record, and hounded agencies for his files. He reconstructed the “pathetically inept” background checks and confronted people he discovered, or suspected, had spread tales about him (they dodged or pleaded innocence). He filed a $10 million lawsuit against the government and persuaded U.S. Sen. Lowell Weicker to read still-classified files; Weicker said Kimball was owed an apology. Kimball dropped the suit in 1987 when the government stated he was not “ever disloyal to the United States.”

Kimball was incensed by his treatment but never embittered, says his daughter Lisa Kimball. “That was the most remarkable thing about my father,” she says. “He remained an optimist” — an optimist who counseled vigilance against the excesses of the security state.

“What does the future hold — as government officials amass more and more data?” he wrote, presciently, in 1983.

Christopher Shea ’91 is a Washington, D.C.-based journalist.

No responses yet