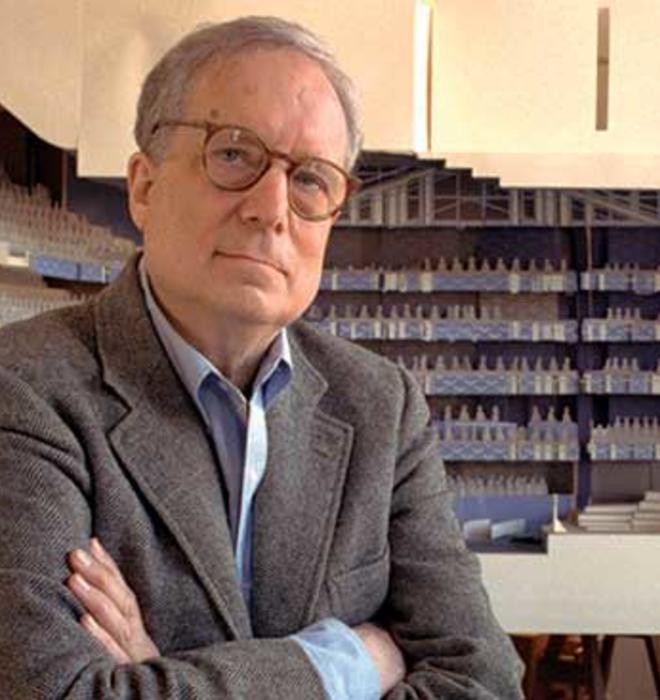

June 25, 1925 • Sept. 18, 2018

ARCHITECT ROBERT VENTURI ’47 *50 credited his studies at Princeton for his love of history, which he translated into a one-of-a-kind style that blended the nostalgic and cutting-edge. At a time when modernism had captured the country’s attention, the work of the Pritzker Prize winner and his wife and partner, Denise Scott Brown, incited both critics and admirers. Venturi came to occupy a singular place in the architectural landscape that will endure long after his death Sept. 18 at age 93.

He felt that the industry’s embrace of spare design ignored “the richness and ambiguity of modern experience,” as he put it in his 1966 book, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. He argued that the stark, boxy structures architects were creating were not in touch with the “messy vitality” of their surroundings.

Venturi and Scott Brown embarked on a quest to understand what America really looked like. The duo famously argued that the flashy architecture of Las Vegas was not only worthy of study — they took a class of Yale students there and went on to publish a book on the topic — but also an important indication of where design was going.

“If you went [to Vegas] as an architect, it was kind of a joke,” says architect Frank Gehry, a friend of Venturi and Scott Brown. “You go there and everything is so exaggerated, you have to do something exaggerated to exist in it. Bob understood that idea. I think he was trying to tell us that our culture was gone wild, gone rogue, and we’ve got to look at it and see what we can learn from it.”

Venturi and Scott Brown’s architectural contributions to the Princeton campus, including Gordon Wu Hall, Lewis Thomas Lab, and Schultz Lab, encapsulate their unique perspective. Architecture critic Paul Goldberger notes the profession’s split between practitioners who sought to mimic historic architecture and those who rejected it. “If you look at something like Gordon Wu Hall, it doesn’t fall into either of those categories,” he says. “It incorporates historical references, but in a much more original and slightly quirky way.”

Each boasting a mix of techniques and styles, the firm’s structures — which include the Seattle Art Museum and the Sainsbury Wing at the National Gallery in London — evade simple categorization. Venturi himself felt incorrectly classified. Many consider him to be the father of postmodernism, a title he rejected — appearing on a 2001 cover of Architecture magazine with the quote, “I am not now and never have been a postmodernist.”

Today, postmodernism is receiving renewed attention as preservationists fight for the survival of its buildings across the country. Interest from new fans and sympathy from past detractors have started to chip away at a decades-long resistance to the trend, which fell out of fashion following its heyday in the ’70s and ’80s. Despite Venturi’s disassociation with the style, his work and writings will continue to be a central part of its rediscovery.

“There’s no question Venturi will loom larger and larger,” Goldberger says. “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture is really one of the seminal books of the 20th century. It will always have things to teach people about how to see and understand architecture.”

Allie Weiss ’13 is a freelance writer and editor.

Watch: American Architecture Now’s Interview with Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown

Courtesy Duke University Libraries

No responses yet