Jan. 25, 1935 • Jan. 14, 2018

DURING HIS CAREER in research and development for toy- and-gaming-industry giants Parker Brothers and Hasbro in the 1960s and ’70s, William “Bill” Dohrman III ’57 brought hundreds of games — including the popular word game Boggle and the iconic Nerf Ball — to children of all ages.

But Dohrmann’s enthusiasm for games began earlier. In a letter published in Sports Illustrated just after his graduation from Princeton in the late 1950s, Dohrmann and a few of his friends shined a spotlight on a burgeoning sport.

“Frisbee is no longer merely a game of individuals throwing the unit about at random as in catch. It can be, and is in some locales, an athletic contest resembling a bullfight in its artistic nature, football in its competitive spirit,” he wrote. “Band music blares from a hi-fi set; Yale, Princeton, Brown, and the All-Stars emerge in eye-catching uniforms; and — well, we honestly feel America has a new sport.”

Though he co-authored the letter with two other self-proclaimed “loyal Frisbians,” Dohrmann’s daughter, Natalie Dohrmann ’87, says, “The language and humor are so my dad. He was the world’s funniest person.”

Dohrmann’s friends and family say his humor and his creativity were his hallmarks. “He was the most imaginative and creative person I’ve ever known. ... No one ever made me laugh as long and loudly as did Bill,” says his Lawrenceville friend and Princeton roommate George White ’57.

That wry humor, and his sense of adventure, helped Dohrmann — who first worked as an ad man — develop toys, such as the now-legendary soft, orb-like ball kids could throw inside the house without fear of inciting their mothers’ wrath. “He loved Nerf,” says Natalie. “It was his baby.”

Dohrmann also led Parker Brothers’ research-and-development department during the sometimes-daunting electronic revolution in the toy-and-game industry. “It’s as if someone reinvented dice,” he told Diane McWhorter of Boston magazine in 1978, remembering the time. Natalie recalls her dad bringing prototypes of electronics like the game Merlin to their home in Connecticut. “He loved everything new,” she says.

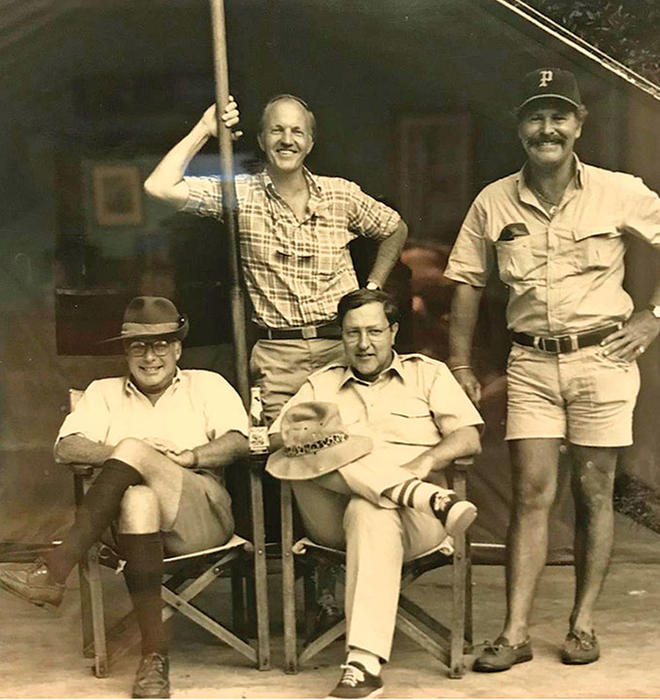

A reader of history, philosophy, and literature who quoted poetry by heart and knew every lyric of the standard American songbook, Dohrmann led his Princeton friends and family to destinations all over the world, White says. Even after he suffered an aortic aneurysm in 2002 that forced him to use a wheelchair, Dohrmann “made sure that his horizons were ever vast,” Natalie wrote in his obituary, with the help of his wife of 28 years, Linda.

The man who learned to love the game of Frisbee on the lawns of Princeton and brought the Nerf ball to the world never stopped making fun and adventure a priority in his life — and he refused to let his friends and family lose their sense of wonder, either.

“That was his legacy,” Natalie says.

Allison Slater Tate ’96 is a freelance writer and editor in central Florida.

No responses yet