April 10, 1926 – Sept. 16, 2020

Bill Danforth ’48 spent much of his life putting Washington University — and St. Louis — on the map. During his 24-year tenure as chancellor, Danforth transformed the school into a top-tier research institution whose faculty, alumni, and medical staff won 10 Nobel Prizes. When he retired from his post in 1995, Danforth went about creating, then leading, the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, a St. Louis nonprofit dedicated to engineering disease-resistant crops to help end global hunger, and gave away many millions of dollars to local organizations through his family’s Danforth Foundation. Then he helped desegregate St. Louis public schools in his role as a federally appointed negotiator, and a decade later co-led an advisory committee to analyze and improve them.

But even in his 80s, he felt his work wasn’t done.

“He said, ‘At my age, I don’t know how many more years I have left, so I have to redouble my effort,’” recalls his brother, former Sen. John C. Danforth ’58. “He was very, very determined that he had to do good things in his life.”

William H. Danforth was born in St. Louis. His grandfather had established an animal-feed company that was the precursor to Ralston Purina, which Danforth’s father subsequently ran. Bill Danforth pursued a career in medicine. After serving as a Navy physician during the Korean War, he returned to St. Louis in 1957 to work as a cardiology instructor at the Washington University School of Medicine. In just eight years, he was named president of the medical school and vice chancellor for medical affairs at the university.

By the late 1960s, students were rioting, and town-gown relations were strained. Washington University’s then-chancellor, Thomas Eliot, sought Danforth’s “advice and counsel on these difficult matters,” says Bob Virgil, dean emeritus of the university’s business school.

Not only did Danforth provide guidance and a steady hand, he was a gifted mediator with an ability to unite people through his modest, deliberate, soft-spoken approach. He had an unwavering belief that Washington University could be an academic powerhouse that would uplift his beloved city of St. Louis, which inspired confidence and trust in those around him. Danforth succeeded Eliot as chancellor in 1971.

“Bill’s greatest talent was his ability to hear other people,” Wayne Fields, the Lynne Cooper Harvey Chair Emeritus in English, wrote in a tribute for Washington University’s alumni magazine. “He cared about people, everyone he met, and respected them regardless of race or gender or economic circumstances.”

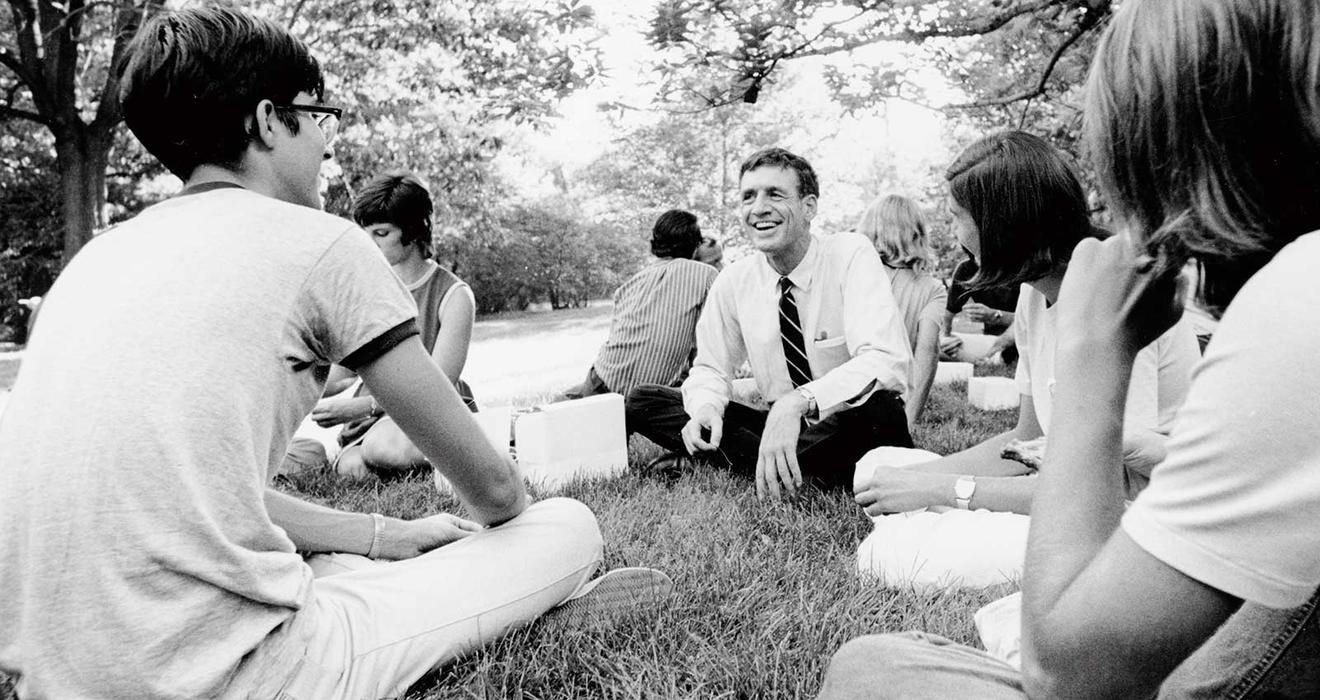

Danforth regularly attended student events and had a ritual of visiting undergraduate dormitories to tell “bedtime stories” — from the history of Washington University to favorite family tales. He knew many of the students, who affectionately called him “Chan Dan,” by name.

Under his leadership, WashU added 70 endowed professorships, tripled the number of student scholarships, and grew its endowment to $1.72 billion — then the seventh largest in the country. He built lasting partnerships between the university and regional hospitals and government.

Ultimately, Danforth’s belief in the potential of Washington University and its impact on the city became reality, Virgil says. “He’s the great St. Louisan of our times.”

Agatha Bordonaro ’04 is a freelance writer and editor based in New York City.

Listen to a remembrance of Danforth from St. Louis Public Radio

No responses yet