The Long Road to Paris

Kareem Maddox ’11 heads to this summer’s Olympics as a torchbearer for 3-on-3 basketball and the Princeton program

ON A FEBRUARY EVENING IN a Colorado Springs high school gym, 16 men take turns playing a breathless version of halfcourt basketball. They pass, dribble, cut, and shoot with no coach in their ear, only the thumping of hip-hop and the pounding of a plum-and-apricot colored ball. A 12-second shot clock pushes the pace, and the requisite “clearing” of the ball behind the arc with each change of possession does nothing to slow the tempo. A shot from beyond that arc is worth two points. Anything else counts only one, so a deep shot delivers a 100% premium, not the 50% of orthodox hoops with its twos and threes. A game lasts 10 minutes or 21 points, whichever comes first. Best to get to 21 now.

This is elite 3-on-3 basketball, aka 3x3, and it has jumped the schoolyard to take a place on the Olympic stage. The discipline demands an enervating combination of haste and concentration and has a way of making even the most accomplished 5-on-5 player look the fool. After failing to qualify a men’s team for the first Olympic 3x3 tournament, in Tokyo in 2021, the U.S. has locked up a spot in this summer’s Paris Games, which lay barely five months off. These trials will determine who wears the red, white, and blue.

Now and then a voice cuts through the wall of sound — that of Kareem Maddox ’11, the 6-foot-8 former Princeton star who has become the face of American 3x3. His voice is a professional one: Before taking his current job in player personnel with the NBA’s Minnesota Timberwolves, Maddox worked as a podcaster and public radio host. Tonight he has no qualms about deploying his pipes. Steeped in the Princeton principles that can be so effective in an uncluttered halfcourt, Maddox has strong feelings about 3x3 best practices, which he shares with teammates in sharp interjections. He whips out a whiteboard during timeouts to amplify those points. But most of his fellow candidates perform the basics instinctually: Keep the lane open. Better to cut than screen. If you pound the ball inside, look to kick it out quickly for that extra payoff. “If the pros went to twos and fours,” says USA Basketball 3x3 director Jay Demings, “you’d probably never see a two-point shot in the NBA again.”

With its nod to extreme sports and the X Games, that “x” in 3x3 is no accident. Alarmed to see the age of the average Olympic TV viewer creep up, the International Olympic Committee and its television partners have embraced sports that skew younger and edgier, like BMX cycling, skateboarding, and beach volleyball. To go with the relentless hip-hop, FIBA, basketball’s world governing body, has introduced further streetball touches: no-autopsy, no-foul officiating, a ban on in-game coaching, a slightly smaller and thus more dunkable ball, and flip commentary. In Tokyo, the public address guy would describe a player as “quicker than a Kardashian marriage,” or a team as “all business, like the front of the plane.”

In fact, organized 3-on-3 has suburban origins that date back to the mid-’70s, when teenage friends in a town outside Grand Rapids, Michigan, played for a few bucks tossed into a hat. Within several summers they had rolled out dozens of these so-called Gus Macker tournaments around the Midwest. Sports marketing executives took notice, grafting corporate sponsorship and a network deal onto the Macker’s homespun basics and launching the result, Hoop It Up, in major metropolitan markets.

“It’s a great way to teach because 3-on-3 breaks the game down into parts. It’s all about the togetherness of three. Never one-on-one, never beating someone off the dribble.”

— Mitch Henderson ’98

Princeton men’s basketball coach

Not long afterward, former Princeton guard and captain John Rogers ’80 caught the 3-on-3 bug. In 1992, he joined ex-Tigers Craig Robinson ’83 and Kit Mueller ’91 in entering Shoot the Bull, a tournament in Chicago’s Grant Park staged by their hometown NBA team. That summer they reached the final four of the elite division and a year later won it all. “It was a magical experience, beating players from all over the country while playing the Princeton system,” Rogers remembers. “Taking only threes and layups is at the heart of what [longtime Princeton] coach [Pete] Carril taught us. It’s stuff you see in the NBA today, only in 3-on-3 it’s on steroids because of all the space.”

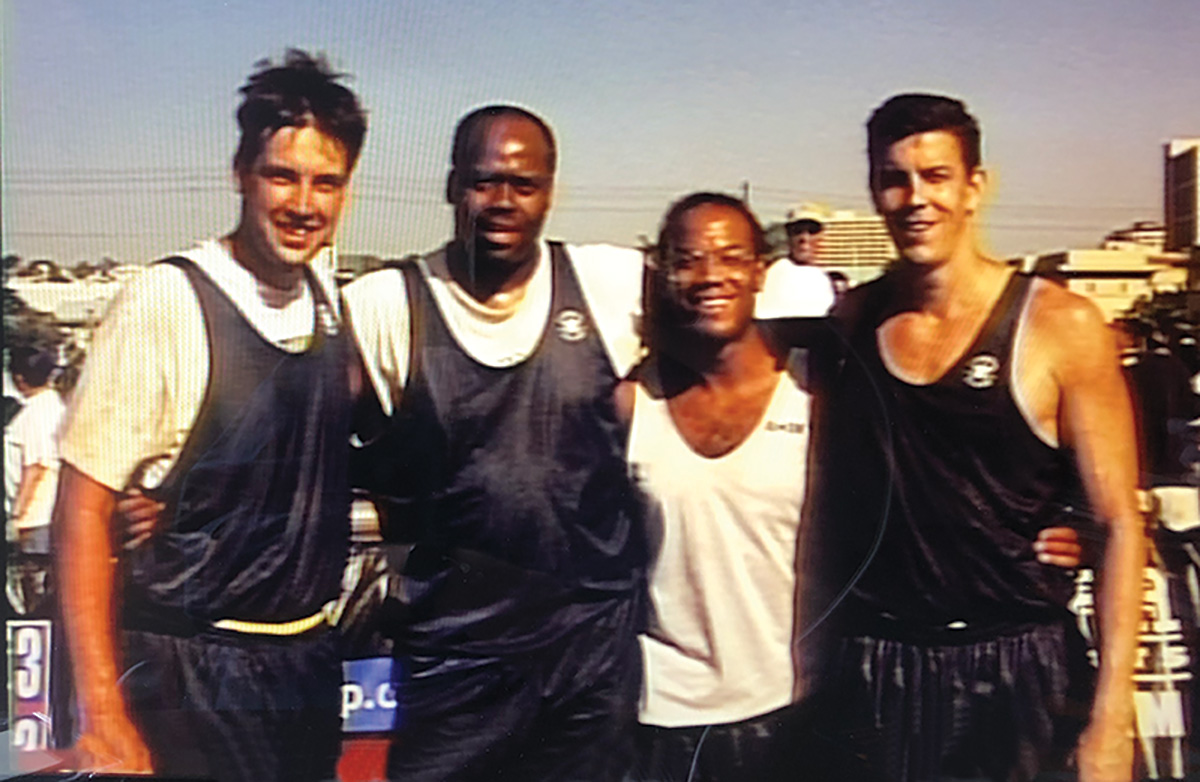

Rogers and his crew — it included the ex-Harvard captain and future Secretary of Education Arne Duncan — wanted more. They won Shoot the Bull two additional times. In 1997, at a Hoop It Up event in San Diego, they lost their first game only to roar back to win the whole thing. For years afterward they made 3-on-3 a part of their lives, entering a half-dozen or so tournaments each summer and winning, Rogers estimates, “80% of them.”

Rogers himself eventually aged out of participating. But he and his Chicago firm, Ariel Investments, kept bankrolling elite teams on the circuit, first under the name Ariel Slow and Steady and later as Team Princeton, which continued to collect Hoop It Up titles, winning nine of 11 possible national championships between 2003 and 2014 as well as multiple events after FIBA established its 3x3 World Tour in 2012. Duncan even qualified for the 2014 Worlds in Russia while he served in the cabinet of Robinson’s brother-in-law, Barack Obama. (Given the diplomatic implications of participating after Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Crimea that year, Duncan had to give those Worlds a miss.)

Not every Ariel or Team Princeton player has had a direct Princeton connection. But whether having played for Robinson at Brown, or for former Tigers coach Bill Carmody at Northwestern, most have been schooled in the Princeton system and its precepts. And several dozen players to follow Rogers, Robinson, and Mueller came straight out of Jadwin, among them Bob Slaughter ’78, Sean Jackson ’92, George Leftwich ’92, Mitch Henderson ’98, Brian Earl ’99, Dan Mavraides ’11, Mack Darrow ’13, and Ian Hummer ’13, with Henry Caruso ’17 and Devin Cannady ’20 currently joining Maddox in the USA Basketball 3x3 men’s player pool. (Cannady’s wife, former UConn standout and current WNBA star Katie Lou Samuelson, qualified for the Tokyo Olympics but contracted COVID-19 and couldn’t play on the U.S. 3x3 women’s team that won the gold medal.) Rogers has also sponsored teams featuring Princeton women, and the U.S. women’s player pool now includes ex-Tigers Blake Dietrick ’15 and Carlie Littlefield ’21. As a result, Demings rhapsodizes about “the John Rogers ecosystem” and its contributions to U.S. efforts during the first dozen years of FIBA-sanctioned 3x3.

“Drive drill,” a staple of Tigers’ basketball practices for more than half a century, is the template for how the orange and black play 3x3. An offensive player dribbles toward a teammate with the option to hand off or, if the teammate’s defender turns his head, send the ball on a bounce to that teammate cutting backdoor to the basket. Many graduate-level wrinkles can be run off “drive drill” — they go by names like “split cut” and “drift action” — and you’re as likely to see these concepts from Princetonians on a 3x3 halfcourt in Hong Kong in August as in Jadwin on a Saturday night in February. Maddox falls in a long line of Princeton “passing pivots” — Mueller and Steve Goodrich ’98 before him; Tosan Evbuomwan ’23 afterward — who could take advantage of space with mobility, ballhandling, and precision passing. “At its core, ‘drive drill’ is Princeton basketball, the guy with the ball thinking, ‘What can I do to create a shot for my teammate?’” says former Princeton captain and coach Sydney Johnson ’97, who coached Maddox in college and has served as a 3x3 assistant with USA Basketball. “It’s perfectly suited to how we see and play the game.”

For a decade before his death in 2022, Carril would attend Princeton practices and serve as a resource for Henderson, the Tigers’ young coach. If Henderson fretted that his offense had gone stale, Carril might suggest a few rounds of 3-on-3 to get the players’ feng shui right. “It’s a great way to teach because 3-on-3 breaks the game down into parts,” says Henderson, who keeps 3x3 video clips on his laptop for inspiration. “It’s all about the togetherness of three. Never one-on-one, never beating someone off the dribble.”

When Henderson himself played on a few of Rogers’ title-winning 3-on-3 teams, the play call “come and get it” might mean, “Go backdoor.” Or a player who yelled “gonna screen for you” would in fact cut away. “Basketball is a game of cunning and guile and trickery,” Henderson says. “As coach Carril would say, ‘Did you never steal candy from the dime store?’”

The ironies abound: that players from Princeton, a program renowned for structure and teamwork, excel at a version of basketball associated with untidiness and individual play; that the basics of an offense often derided for being slow can work so well at a high tempo; and that a discipline introduced to the Olympics for its appeal to youth rewards what pickup ballplayers call “old man game” — fundamentals, savvy, and deception.

Sure enough, more than half the players in this weekend’s 3x3 trials are age 30 or older. Maddox himself is 34. Between graduation in 2011 and his arrival here on the cusp of the Games, Maddox has more than a dozen years to account for — and prior to that, a fascinating story as well.

IT'S ONE OF THE FEW TIMES IN Kareem Maddox’s life that he remembers not being tall enough. His father, Alan, had scored tickets for the men’s 200-meter final at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, where 6-year-old Kareem needed to stand on his seat to glimpse Michael Johnson bolting through a cauldron of noise to shatter his own world record. From Johnson’s gold shoes to his upright running style, the scene imprinted itself upon him. “My first Olympic dream moment,” Maddox calls it.

During the summer of 2010, Maddox played in several 3-on-3 tournaments while interning at Ariel. There followed an epic senior season at Princeton — an Ivy title and NCAA Tournament appearance, plus recognition as first team All-Ivy and the league’s Defensive Player of the Year — and then gigs with club teams in the Netherlands and England. Whereupon he responded to what he calls “a nagging voice in my head” that said, “Time to get a real job and move on with your life.”

Over the summer of 2013, he showed up at KCRW, the National Public Radio affiliate in his hometown of Los Angeles. “I volunteered two days a week,” he says. “Then four. No one stopped me. Eventually they said, ‘OK, we’ll pay you.’” He loved storytelling and, as befit someone with an A.B. in English, had a knack for it. In 2014, he hooked on with the public affairs show To the Point and then the Denver studios of Colorado Public Radio. That’s when he entered a national 3x3 tournament in Colorado Springs, where he and Darrow narrowly lost in the semifinals. Sensing a story, Maddox had driven down with his audio equipment, and before leaving recorded an interview with U.S. 3x3 national coach Joe Lewandowski, who told him the discipline would likely become an Olympic event. “It was my first touchpoint with USA Basketball and 3x3,” he says. “I played pretty well. And I got the spark back.”

CPR soon assigned Maddox to be local host for All Things Considered at KUNC, its affiliate in Greeley. (“Stories that matter, voices you trust. This is Kareem Maddox, thanks for being with us.”) His shift ran from 2 p.m. to 7 p.m., and with little else in this northern Colorado town calling to him, Maddox began spending mornings in a gym with a full court. Alone with a ball and a basket, he started to unlock a part of the game he had long overlooked. “In college I’d never shot,” he says. “I wasn’t a bad shooter — we just had better shooters.”

Back on campus for Reunions in 2016, Maddox bossed the annual alumni game and heard Henderson ask him why he was no longer playing. At the same time, watching that year’s NBA Finals between the Golden State Warriors and Cleveland Cavaliers, he felt stirrings of inspiration as the Warriors’ Stephen Curry seemed to obliterate the boundaries of what a shooter could do. “Shooting was a craft, but Curry turned it into a fine art,” Maddox says. “I wanted to keep creating beauty that way. I’d find myself getting into a flow state, that sweet spot between moving and thinking.”

How do you unretire at age 26? For Maddox, it involved a summer showcase in Las Vegas in front of agents angling to place players with club teams overseas. He was woefully out of game shape, but the caffeine from a couple of preworkout shakes helped him play well enough to attract the interest of a team in Poland. Freshly promoted, the club had little budget. Maddox didn’t care. That season he sank 37% of his three-pointers.

The following summer came official word that 3x3 would be on the Olympic program. Memories of Atlanta and Michael Johnson flooded back, lifting a goal into view. Maddox began to tell family and friends that he was gunning for the Games.

In 2018, he took a mostly remote job as a producer for Gimlet Media, the podcasting studio, and threw himself into the FIBA 3x3 World Tour as a member of Team Princeton. As on the pro tennis tour, players accumulate points according to how they perform, with rankings determining whether they or their countries qualify for capstone FIBA events. On a Wednesday, Maddox would board a plane bound for Beijing or Prague or Hyderabad or Mexico City. His might be the lone seat with a burning overhead light, as he edited audio on his laptop for his day job. Then he’d fly home Sunday night, gassed but with ranking points in tow. “So much of 3x3 is just who wants to be there,” he says. “Who wants to travel to Mongolia and not complain about the food?”

A year later, Maddox and Team Princeton broke through. They won the FIBA World Cup, sweeping all seven games in the shadow of Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, in the most dominant World Cup performance on record. A few months later, Maddox was named tournament MVP as Team Princeton captured the FIBA World Tour stop in his hometown. Throughout he deployed not only his newfound touch from distance, but also his chops as a passer who could crisply clear, kick, or swing the ball, and as a defender with the length to disrupt opponents’ passes and shots. “They call 3x3 the 10-minute sprint,” he says. “It’s all explosive movement. Sprints from under the basket to the arc, then changing pace within the 12-second shot clock.”

Just as Team Princeton was finding its groove, the pandemic hit like a flagrant foul. Back in L.A., his old high school coach let Maddox use the gym, and through voice memos and direct messages he tried desperately to keep the team connected. But, he says, “game-play chemistry doesn’t come from group chats, and other countries were being more permissive [with COVID protocols].” A roster tweak, then a late injury that forced another substitution, and Team Princeton “wasn’t where we needed to be” for the qualifying tournament for Tokyo, Maddox says. “This is such a chemistry sport, and we ran into a hot-shooting Dutch team.”

Maddox was gutted. Unexpected therapy came as he worked on “The Greatness with Kareem Maddox,” a podcast series for which he chased down Olympic icons, from Native American distance runner Billy Mills to Trinidadian sprint medalist Ato Boldon. In the final episode, from August 2021, Maddox turns the tables and invites Boldon to interrogate him about his own unavailing Olympic quest. Failure to qualify remained painfully fresh. “I’m frustrated and embarrassed and angry about it,” he tells Boldon. “Not being able to finish the task, you feel fraudulent in a way.”

Maddox wants to know: When is it time to stop chasing the dream? Or as he further frames the question, “I do both these things” — audio storytelling and 3x3 — “kind of well. Which do I want to be great at?”

Boldon diagnoses Maddox’s struggle as one “between the practical and the possible.”

But Maddox also noticed a strange thing happening. When others would ask him about the Olympics, and Maddox would explain how the U.S. men had fallen short, “people were even more supportive. ‘Damn, you just missed it. You gonna try again?’”

Which helped resolve his dilemma.

USA Basketball learned well the lesson of its failure to qualify for Tokyo. For the Paris Olympic cycle, Demings and Lewandowski chose to field a de facto national team and give it as much runway and support as possible. From Team Princeton they plucked Maddox and the son of Hall of Famer Rick Barry, 6-foot-6 Canyon Barry, who had played at Florida and in the NBA’s developmental G League. To add shooting and international seasoning, they recruited a 5-on-5 stalwart, 6-foot-2 guard Jimmer Fredette, who had led the nation in scoring at BYU before logging seven seasons in the NBA and five more in China and Greece. Supplemented by a 6-foot-3 former Division II grinder named Dylan Travis, and playing under the banner of Team Miami, the four won gold at the 2022 FIBA 3x3 AmeriCup in their namesake city; added silver at the FIBA 3x3 World Cup; won medals at four World Tour events, including golds in Cebu and Abu Dhabi; and took gold at the 2023 Pan Am Games. By last fall they had collected enough points to clinch an Olympic berth in Paris for their country.

About a week after those trials in Colorado Springs, propping his phone up against a coffee mug, Maddox logged on to a Zoom call with Demings and USA Basketball chief Jim Tooley. They were calling to share news that he and Team Miami, fully intact, would be lacing up their sneakers for the U.S. at the end of July on the Place de la Concorde.

As the lone holdover from the pre-Tokyo failure, with a 3-on-3 pedigree of more than a dozen years and Olympic fandom dating back to childhood, Maddox was overcome. “I’ve thought for years about what I’d say at this exact moment, other than thanks,” he says. “But the best way to show our gratitude is to put in more work and get it done this summer.”

Maddox had long felt awkward mentioning to others his goal of making the Olympics as a basketball player. He worried that it might sound grandiose — “because I’m Kareem and you haven’t heard of me.” But 3x3 is truly an enterprise in which individuals recede into the whole. “The most Princeton thing about 3x3 is that selfishness is taken out of the equation,” Maddox says. “We’ve got 10 minutes to win this game and it doesn’t matter how.”

Back in 2011, John Rogers and his A team turned up for a Hoop It Up event in Camden, New Jersey, and Henderson, who had just been named the Tigers’ coach, drove down from Princeton to play, with Carril along for the ride. Ariel wound up winning. As Rogers remembers, “Coach loved that we were all hanging out together. Multiple generations of Princeton players, playing ball and drinking beer and winning. It was his nirvana.”

Today, as he tries to distinguish the Tigers’ program from others during an era marked by such disruptions as the transfer portal and NIL enticements, Henderson touts Princeton to recruits as “a four-year experience.” In fact, he could be selling a 30-year experience. “The beauty of Princeton basketball,” he says, “is that John was Class of 1980. I’m 1998. And Kareem is 2011. And we’ve all done this, winning titles while honoring the way we were taught.”

Alexander Wolff ’79 spent 36 years on staff at Sports Illustrated. He is the author of seven books about basketball and co-editor of World Class, a collection of the journalism of the late Grant Wahl ’96.

THE BASICS

How to Watch 3X3 Olympic Basketball

How many players are on each team?

Four. Teams are allowed one substitute per game,

with players tagging in during stoppages in play.

What is the size of the court?

The Olympic 3x3 court is 49 feet wide by 36 feet deep and has one basket. (By comparison, a regulation NBA court is 94 feet long by 50 feet wide and has hoops at each end.)

How does scoring work?

A shot made beyond the arc is worth two points, a shot from inside the arc is one point, and a successful free throw is one point. A player fouled in the act of shooting is given one or two free throws depending on whether the attempted shot was in front of or behind the two-point arc.

How do you win?

The first team to 21 points wins, but if neither team reaches 21 points in 10 minutes, the team with the most points wins.

What is the format of the Olympic tournament?

There are eight teams each for men and women. The tournament starts with pool play and all eight teams playing each other once. The top two teams in the standings advance to the semifinals and the bottom two teams are eliminated. The other four teams (third vs. sixth and fourth vs. fifth) meet, with the winners advancing to the semifinals. The winners of the semifinals play for the gold medal and the losing teams compete for the bronze.

1 Response

Rocky Semmes ’79

1 Year AgoThe Olympic Spirit vs. the Profit Motive

The impeccable writing and reporting that characterizes the consistently charismatic content of the Princeton Alumni Weekly exposes how the Olympics has become a predominantly craven commercial concern for calculated corporate benefit (“The Long Road to Paris,” July/August issue). The Olympic spirit was originally a globally shared thrill at human athletic excellence, celebrated magnanimously outside of all politics and nationalities. But inevitably, in the course of human events, such dreams get cloudy and become obscured.

The Olympics devolved into a showcase for nationalist egos and political scorekeeping. And though the original grand and noble Olympic spirit is still trumpeted as the theme of the spectacle, this is now only a marketing smokescreen. Regrettably the Olympics now is primarily and predominantly the cash cow for the International Olympic Committee (IOC), its television partners, and the associated corporate sponsors. All else about the spectacle is subordinate to this reality.

The PAW reflects as much, reporting how “Alarmed to see the age of the average Olympic TV viewer creep up, the International Olympic Committee and its television partners have embraced sports that skew younger and edgier ... .” Cha-ching. Perhaps singer/songwriter Cyndi Lauper in 1983 was onto something when, for her debut album, she recorded the song “Money Changes Everything.”