The Man Behind the Curtain

Andrew Golden steps down from Princo after building a $34.1 billion endowment. How should that money be invested and spent going forward?

COMPREHENDING THE SIZE OF Princeton’s endowment — $34.1 billion at the start of the current fiscal year — challenges the imagination as much as the spreadsheet.

By total size, it is the fourth largest private university endowment in the world, trailing only Harvard, Yale, and Stanford. (The University of Texas System’s endowment, which is also larger, is a composite of several smaller colleges and health systems.) But Princeton’s is the largest on a per-student basis. Divide the endowment by Princeton’s enrollment, and it comes out to a staggering $4.3 million per student.

For fun, consider a few comparisons. Princeton’s endowment is roughly the size of the gross domestic product of Cyprus, nearly as big as the annual budget of the U.S. Department of Labor, and as much as Americans spend each year on bottled water. If the endowment were converted into one dollar bills, the stack would stretch from Princeton to Phoenix. It is even slightly bigger than the estimated net worth of philanthropist MacKenzie Scott ’92 (a mere $33 billion, according to Forbes).

Viewed more spiritually, the endowment is the engine that drives Princeton’s success. It pays to attract a top-notch faculty, keeps the campus trim, fuels the current construction boom, stocks the labs and libraries, funds the graduate stipends, and makes possible the no-loan financial aid policy which in turn enables the University to increase its racial and economic diversity. It is not too much to say that the endowment is a large part of why Princeton tops the U.S. News & World Report rankings of American universities every year.

Yet, in the eyes of critics and protesters, the endowment is symptomatic of a growing divide between elite institutions and everyone else, and is complicit in, among other things, despoiling the environment and enabling genocide. It is, as one climate change protest sign said, “Dirty $.”

Spend any time imagining $34.1 billion, and the mind cannot help but venture into simile. The endowment has been likened to a perpetual motion machine. (Writer Malcolm Gladwell’s phrase.) Or a printing press churning out money. Or a goose laying golden eggs.

When asked if there really is such a goose hiding in the nondescript offices of the Princeton Investment Co. (Princo), the entity that manages the endowment, Andrew Golden only smiles.

“I have to be silent on that,” he says. “Silence is golden.”

The pun is intended. Golden, Princo’s president, is known for his sense of humor as well as his investment acumen. Not that he is known, at least to the average member of the University community. Golden, who is retiring on June 30, is only the third president in Princo’s relatively short history, and though he keeps a low profile, he is by far the University’s highest-paid employee, earning nearly $4 million in total compensation in 2021, according to the University’s tax return, which also credits Golden with more than $5 million in previously reported compensation. (President Christopher Eisgruber ’83, by comparison, made about $1 million.)

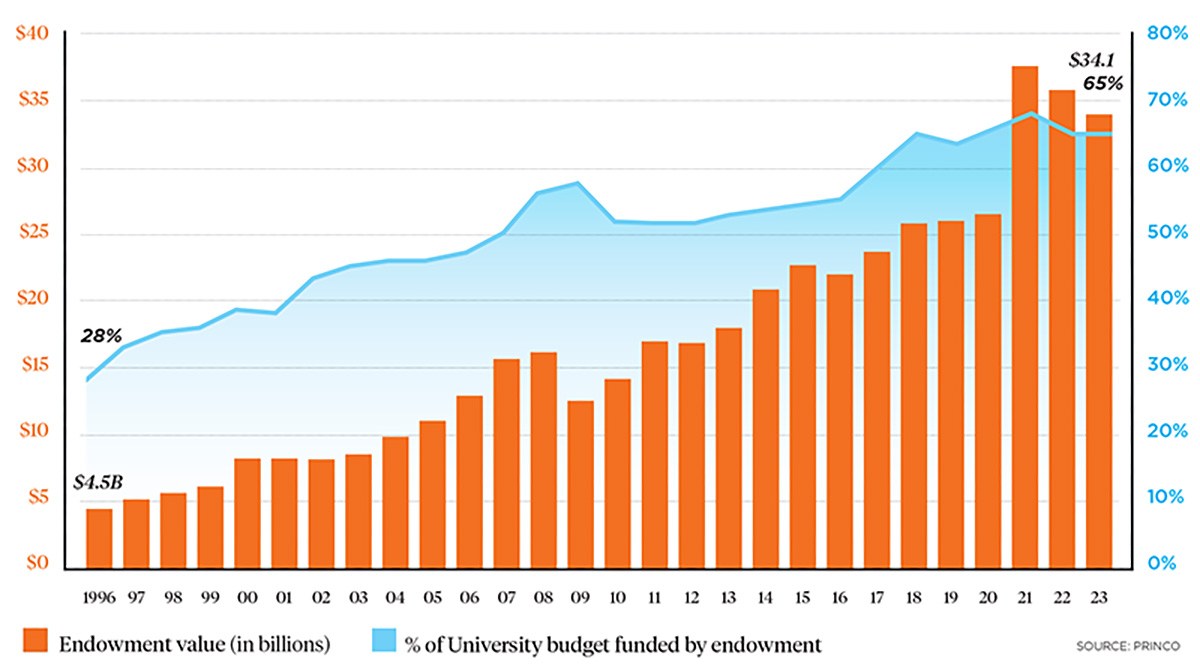

During his 30-year tenure, Golden has seen the endowment grow more than tenfold. Despite falling slightly in each of the past two years, Princo has also hit some upper deck home runs, most recently in 2021 when the endowment boasted a 46.9% return. Even so, Golden’s background seems highly unusual for someone in his post; he was a philosophy major who once aspired to be a professional photographer and enjoys paddleboarding in his spare time.

“Andy is the quintessential good university citizen,” says University Vice President for Finance and Treasurer Jim Matteo. “He knows that his ultimate job is to help fuel what is great about Princeton and what makes the University great.”

Golden will be succeeded by Vincent Tuohey, currently a director for MIT’s investment management company, on July 1.

Most alumni don’t talk about the size of the endowment, except perhaps to wonder why Annual Giving keeps asking for another $100. Recently, though, the endowment has been having a moment, driven in part by Golden’s upcoming retirement, but also by calls that the University should spend even more of it, as well as demands that it divest from disfavored causes ranging from fossil fuel extraction to the state of Israel.

As was the case in Aesop’s fable, many have strong views about what should be done with the golden eggs of Princeton’s endowment. Far fewer, however, know exactly what it is or what it does.

The Golden Era

How the endowment’s value and the percent of the University’s annual budget that has been covered by the endowment have changed during Andrew Golden’s tenure:

Golden set out to provide this information in a Wintersession class he and Matteo taught in January. Titled, “Understanding Princeton’s Endowment: Mission, Math, and Myth-Busting,” it might as well have been called, “The Endowment for Dummies.”

Last year, distributions from the endowment equaled $1.6 billion, and over the past 20 years, it has contributed $18.4 billion to Princeton’s budget, according to documents provided by Princo and the University. Those returns now provide about two-thirds of annual operating revenues and more than 70% of the financial aid budget. (Yale’s endowment, by comparison, supports only about 47% of its operating budget.)

If the endowment is not really a pile of golden eggs, neither is it a pile of gold ingots sitting in a vault. In fact, the endowment isn’t really “located” anywhere — or rather, it is located in lots of places: in stocks, bonds, hedge funds, startups, and real estate. In all, the endowment consists of more than 4,700 separate accounts across six asset classes. Ranked by size, they are private equity (accounting for 30% of the endowment’s value); hedge funds (24%); real estate and natural resources (18%); public equities in developed markets (12%); public equities in emerging markets (8%); and fixed income and cash (8%).

Princo’s staff of 46 works out of two floors on Chambers Street. Although Princo is organizationally distinct from the University, all are University employees. Golden reports to Eisgruber as well as a 12-member Princo board of directors.

Golden only half-jokingly attributes his success to “a comfort with taking credit for the work of others,” describing Princo as “a manger of managers.” What he means is that, while Princo sets overall goals, it does not make specific investment decisions. That work is done by more than 70 outside managers, located in 35 countries worldwide, whom Princo hires to run the day-to-day investing. Here, as in many other areas, Princeton can access the best talent in the world, and benefits accordingly.

Some of those managers, such as Wall Street-based John W. Bristol & Co. Inc., have managed Princeton’s money for decades. But if it thinks they show promise, Princo also takes chances on relatively unproven managers who can provide big returns down the road. Over the years, investment managers have helped Princeton get in on the ground floor of some huge winners, including McDonald’s and Instagram.

While Princo does not micromanage, Golden emphasizes the importance of maintaining a close relationship with its outside managers, not only to review their performance but to share institutional wisdom and ensure that they understand Princeton’s goals and values. “We do go deep into understanding the decisions [managers] make, but it’s really so that we can understand how they make decisions and understand more about the organization,” Golden explains in a sit-down interview with PAW. “What we’re really making a bet on is that each of our managers will grow in a way that allows them to maintain an edge within their arena.”

Just as Princo searches for overlooked investment opportunities, Golden says it seeks “undertapped pools of talent” by expanding the diversity of its managerial roster. Seventy percent of the firms Princo has hired over the past five years have been owned by women or minority groups. Overall, according to a 2022 report by the Knight Foundation, nearly 27% of the Princeton endowment’s U.S.-based assets were managed by firms that are at least half-owned by diverse groups, a rate that far exceeds that of other schools in the survey.

The mission of the endowment is twofold: to spend as much of it as possible each year, subject to “preserving purchasing power into perpetuity,” as Golden puts it, and providing a spending stream that is relatively predictable so programs and departments can plan and don’t have to make sudden cuts in down years.

“Endowments are made to be spent,” Golden said at Wintersession, but not too much and not all at once, if the University hopes to provide for future generations the way it provides for this one. Golden calls this “intergenerational equity.” All individual investors have a time horizon, however long that might be, but universities do not. They hope to go on forever, an outlook that enables Princeton to invest in ventures that might not pay off for many years.

“Donors give endowment funds as a way of buying a little bit of immortality,” Golden said at Wintersession. “There is something at Princeton that they care about and want to go on forever.” That does, however, constrain the University’s hand. Fifty-five percent of the endowment is restricted, meaning the University is only allowed to spend the income it generates and not the corpus, and 70% is designated, meaning the money can be used only for a particular purpose, such as a scholarship or an endowed chair or buying books for the library.

The University has set a goal of spending between 4% and 6.25% from the endowment annually. (It spent 4.53% in 2023.) In order to meet that goal while accounting for inflation and maintaining the endowment for the future, Princo must seek returns of more than 10% per year, according to Princo. Over the past 20 years, the endowment has boasted a 10.5% annual return — 10.8% over the last 10 years — which puts it in the top 1% of all institutional investors.

The edge Princo enjoys from its managers’ expertise is astonishingly large. According to Golden, if returns on the endowment had been just 0.10% smaller over the course of his 30-year tenure, while spending and gifts had remained the same, the endowment would be 15% smaller than it is today. If Princo had an annualized investment return equal to the median return among the 40 largest endowments during that period, the endowment would be just $4.9 billion — 85% smaller than it is.

“Andy has consistently said that, since we have an infinite life, let’s take judicious risks with the right people in growth areas of the economy and that will do well for us over the long term,” explains Kevin Callaghan ’83, a Princo board member. Or as another board member, Nancy Peretz Sheft ’88, adds, “He’s not chasing every upturn in the market.”

Sometimes, as in 2022 and 2023, that has meant losses, most of which were attributable to the venture capital market. “When you invest over the long term, and when you want to add value over what you get in the market, you have to be willing to put yourself in the position of not doing well every year,” Golden explained at Wintersession.

Although Princeton began receiving gifts even before its charter was granted, it did not have anything formally called an endowment until shortly before the Civil War. As The New Princeton Companion puts it, “Until the early twentieth century, Princeton had little endowment to manage and devoted little attention to managing it.” By 1875, its endowment was less than a quarter the size of Columbia’s, and for decades thereafter, the University lived hand-to-mouth, appealing to wealthy alumni to make up annual budget deficits.

Two men changed that: President John Grier Hibben 1882 *1885 and Dean Mathey 1912, a New York bond salesman (later a longtime trustee), whom Hibben deputized as the University’s unofficial endowment manager. Thanks in large part to Mathey’s savvy investing decisions, such as getting out of the stock market just before the 1929 crash and back into it at the start of the postwar boom, Princeton’s endowment quadrupled during his tenure, which lasted until 1960.

For most of the next two decades, endowment strategy was overseen by a trustee subcommittee, but the University continued to run deficits as faculty salaries lagged and building maintenance was deferred. In 1977, the trustees decided to delegate day-to-day management of the endowment to four outside advisers. A decade later, in 1987, when the endowment was $2.2 billion, Princo was created. At around the same time, endowment managers moved away from lower-yielding bonds into riskier areas such as private equity, venture capital, and emerging markets, which generate higher returns.

Golden, who started at Princeton just as the endowment began to take off, was an unusual hire. In a sense, he was like one of those shrewd bets Princo likes to make.

He majored in philosophy at Duke, but a more formative experience was editing the yearbook, which piqued a childhood interest in photography and got him thinking about becoming the next Ansel Adams. While trying to establish himself as a professional photographer, Golden worked as a stagehand, tended bar, and delivered refrigerators, finally landing a job as a graphic artist in North Carolina.

Following his wife to Philadelphia in the early 1980s, Golden supervised the in-house advertising team for a large department store, overseeing fashion spreads and catalog shoots. His move into the world of investments came in stages. Working for the department store got him interested in how organizations work, so he applied to the Yale School of Organization and Management. While waiting to start in New Haven, he took a job with a small money management firm where he began to learn about finance. When he arrived at Yale, Golden thought he might want to pursue socially responsible investing, but a meeting with a friend in the Yale Investment Office convinced him that he could do more good for society working on the endowment. Golden started as an intern and joined the endowment team even before finishing his degree.

After five years in Yale’s investment office, Golden was nearly lured away to work at Princo but chose to become investment director at Duke’s management company instead. Just a year later, Princo called back, this time to offer Golden the president’s job.

Those who have worked with Golden identify several traits he has brought to Princo besides his sharp investment eye. One is relentless curiosity. Another is building a sense of collegiality among his team. Most of Princo’s staff work in a large, open space, like a trading floor, where Golden’s desk is only one of many.

“Andy has high intellect, good judgment, and a willingness to be iconoclastic when it’s appropriate,” says Bob Peck ’88, the Princo board chair. Iconoclasm means more than a willingness to zig when others zag. To Peck, it means a sense for anticipating when others are going to move and getting there first, as well as an ability to recognize patterns in market behavior while knowing when to deviate from them if circumstances warrant.

As with the goose and the golden eggs, everyone has ideas about what to do with Princeton’s wealth.

A few have gone so far as to propose that Princeton simply eliminate tuition altogether. Gladwell suggested this most famously in a 2022 blog post, writing, “Princeton could let every student in for free. The university administrators could tell the U.S. government and all its funding agencies, ‘It’s cool. We got this.’”

Not surprisingly, Golden and Matteo see matters differently.

First, the current tuition, room, and board (about $79,000) still does not fully cover the annual cost of educating a student, which is closer to $120,000. Second, the University already enables students whose families earn less than $100,000 to attend for free, and its financial aid policy means that all who are eligible will graduate without incurring debt. Beyond that, they say, students from wealthy families who can pay something, should.

Furthermore, the money taken from the endowment is already fully committed, so any earnings used to replace lost tuition would have to be diverted from other programs. If the University took enough to provide a tuition-free Princeton, it would deplete the endowment over time, violating the principle of intergenerational equity by privileging current students over those to come.

A much more contentious issue is divestment. Golden passes on questions about specific areas of divestment, quipping that they are “above our pay grade” and are made by the University’s Board of Trustees.

Without addressing any particular cause, though, Golden, who spoke with PAW before the student encampment in late April, summarized his own views about how divestment decisions should be approached. “I often hear people say, I wish that the endowment would reflect my own values,” he says. “Well, that’s not entirely correct. The endowment should reflect the values of the entire University community, which more often than not are messy and contradictory.”

Divesting a portion of the endowment does happen, but rarely, and it takes time. Over the past 40 years, the trustees have done so on only three occasions: from companies doing business in South Africa (1985), from companies abetting genocide in Darfur (2006), and from fossil fuel companies (2022). Several other divestment pushes, including one from Israel in 2014, have not succeeded.

In a 2017 statement, Eisgruber framed the issue as follows. “Divestment initiatives ... require special care, not only to avoid the risk of orthodoxy but also to respect the promises that Princeton has made to its donors,” he wrote. “We agree to use and manage their gifts to advance Princeton’s educational mission, not to make political statements.”

Princeton being Princeton, there are defined procedures for when and how to seek divestment. According to guidelines adopted by the trustees in 1997, there should first be a recommendation from the resources committee of the Council of the Princeton University Community (CPUC), which in turn should follow a three-part test:

1. There must be “considerable, thoughtful, and sustained campus interest” on an issue involving the actions of companies within Princo’s portfolio;

2. A “central University value” must be at stake;

3. There must be “a consensus on how the University should respond to the situation.”

That word “consensus” can be tricky. As Professor Jay Groves, the current chair of the resources committee, said at the April CPUC meeting, consensus does not mean unanimity, but it does mean more than a majority, citing a 2020 undergraduate referendum on fossil fuel divestment, which passed with 82%, as an example. When it comes to consensus on divestment, Groves said, “I think the committee has a sense that we know it when we see it.”

“I often hear people say, I wish that the endowment would reflect my own values. Well, that’s not entirely correct. The endowment should reflect the values of the entire University community, which more often than not are messy and contradictory.”

— Andrew Golden

To those demanding divestment, however, causes such as climate change or the fate of Palestinians can’t wait. “We cannot as people of conscience stand idly by and claim to be in the service of humanity only when it is popularly palatable and financially expedient,” declared a petition by the group Princeton Israeli Apartheid Divest (PIAD) when it began its encampment. Among other things, PIAD demands immediate divestment from “all companies that profit from or engage in Israel’s ongoing military campaign, occupation, and apartheid policies.”

Process and protest met head-on at a contentious meeting on May 6 between Eisgruber, two other senior administrators, and a group of students, faculty, and alumni supporting the protests. The meeting came 11 days into the encampments at McCosh Courtyard and Cannon Green and four days into a hunger strike by 13 students.

While offering some concessions on other issues, according to a statement issued afterward by the University, Eisgruber insisted that any group seeking divestment go through proper channels. He later explained this further in an email to the University community, writing, “I have told [protesters] that we can consider their concerns through appropriate processes that respect the interests of multiple parties and viewpoints, but we cannot allow any group to circumvent those processes or exert special leverage.”

In the end, the endowment is practical, not poetic. Perpetual motion machines and magical geese don’t exist. What has made Princeton’s endowment so big is a positive feedback loop of very wealthy and loyal alumni, access to expertise, a willingness to take risks, and an ability to play the long game when it comes to investing.

In good years, the ability to invest for high stakes enables the wealthiest schools to reap huge returns. “More zeroes in means more zeroes back,” a recent survey of endowments by the website BestColleges.com put it. It has helped Princeton build an 11-digit endowment. But most colleges and universities are not so fortunate. According to a 2015 survey by Moody’s Investors Service, the 40 richest schools control about two-thirds of total educational wealth in the United States, a gap that has likely grown since then.

When it comes to university endowments, it seems, the rich do indeed get richer.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to clarify the breakdown of Golden's 2021 compensation.

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

2 Responses

Martin T. Kavka ’92

1 Year AgoMistaken Identity?

Thanks for the informative and fascinating article in the June issue about Princeton’s endowment, and Andrew Golden as he steps down as president of Princo. But why was the story accompanied by photographs of David Letterman? I await PAW’s acknowledgment of its error, and publication of images of the real Andrew Golden.

Lewis Shilane *73

1 Year AgoReturn on Endowment

According to the June 2024 article “The Man Behind the Curtain,” “Over the past 20 years, the endowment has boasted a 10.5% annual return – 10.8% over the last 10 years …” In the same 10-year span (July 2013 through June 2023), the annualized return on the S&P 500 has been 12.2% (with dividends reinvested), along with a 9.8% for the past 20 years and 9.9% over the past 30 years. So maybe Princo doesn’t need 4,700 separate accounts across six asset classes, with 46 local employees and more than 70 outside managers located in 35 countries.