Marking time

Combining history and archaeology, these Princeton scholars reconstruct daily life in the fields of Turkey

At the entrance to a mosque in Kozören, a small farming village in central Turkey, Princeton history professor John Haldon leans to the right, dips his shoulder, and cranes his neck to read the inscription on a large, cylindrical stone. In addition to being upside down, the rows of Latin letters have been scratched and eroded over hundreds of years. But Haldon requires little time to identify the marker’s original purpose. In the second or third century, long before it became a pillar for an iron gateway, this milestone stood alongside the Roman road to Amasya, a town about 25 miles east of Kozören. It is the first Latin inscription that Haldon and his colleagues have found in their two seasons of research in the region. Most local inscriptions are in Greek, the preferred language of the Byzantine Empire.

As Haldon examines the inscription, colleague Jim Newhard, a classicist from the College of Charleston, trains his eyes on a hand-held computer, zooming in on a satellite image of the region to locate the exact spot where the Roman milestone now stands. On the other side of the narrow stone road next to the mosque, Hugh Elton, a historian from Trent University in Canada, speaks with a local farmer about other inscriptions and artifacts near the village.

Within 10 minutes, villagers lead the researchers to several stones recycled for modern uses, including a sarcophagus that now serves as a drinking trough for livestock and an inscribed block that has been reused in the foundation of a barn. After thanking their impromptu guides and sipping cold ayran, a salty yogurt drink, the three men return to their rented Ford Focus to follow another lead. From the passenger seat Haldon quips, “Well, that was a good start.”

A few chunks of ancient limestone might seem pedestrian compared to the precious objects that accompany Hollywood’s portrayals of archaeology — lost cities, gold-laden tombs, and the like. But Haldon, one of the world’s leading Byzantine scholars, did not come to this area of the Anatolian plateau to search for treasure. He chose to center his research at the nearby village of Avkat, paradoxically, because “it wasn’t important.” Not in the traditional sense, at least. Avkat was the medieval equivalent of a one-horse town, occupied by peasant farmers and herders and a few state and church officials. It housed one modest landmark — the burial shrine of Theodore the Recruit, a soldier-saint once revered in the region — and produced little wine or olive oil, the region’s most prized consumer goods during ancient and medieval times.

The Byzantine Empire, depending on how one defines its beginning, spanned about 1,000 years, ending with the fall of Constantinople — now Istanbul — in 1453. At its height, as much as 90 percent of the empire’s population likely lived in small, rural towns like Avkat and its surrounding area, but relatively little is known about how these residents lived or how they communicated and traded with their neighbors. The Avkat project aims to address basic but important questions about how people lived, labored, and traveled in the region, from prehistoric times to the Ottoman era. Work is not limited to Avkat or its immediate neighborhood: Over a 10-year period, Haldon and his colleagues hope to survey parts of an area that covers nearly 600 square miles of central Anatolia. In the process, they will employ technologies like those used in Newhard’s hand-held computer to organize the information they gather and share it with other researchers.

In July and August, the Avkat project conducted its first full season of field research. The project’s permit from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism does not allow any digging in the first five years of the survey, so the team relied on noninvasive techniques to gather data. A group of world-renowned geophysicists from the United Kingdom used imaging tools to find shapes of structures beneath the surface of a hill overlooking the village of Beyözü (which stands where Avkat, or Euchaïta in the Byzantine era, is believed to have been located). An expert in environmental sciences came to the site to see if he could draw relevant historical data from calcite deposits in nearby caves. Students and professors from five universities, including one in Ankara, interviewed local residents and catalogued objects or pieces of medieval architecture incorporated in the modern town. And three teams of students gathered information through field walking, a systematic method for collecting shards of pottery, roof tiles, stone tools, and other evidence of human habitation, agriculture, and warfare through history.

Haldon, an affable Englishman who joined the Princeton faculty in 2006, has worked in the field off and on since he was in high school more than 40 years ago, and the students in Turkey relish his stories of past adventures. There was the winter dig in England’s Cheddar Gorge, where the ground was hard enough to break a pickaxe. And the night in a Bulgarian prison for some unintentional offense committed on a train while returning from a dig.

He explained the roots of the Avkat project during a drive from Ankara to Beyözü in July, a four-hour trip through a rocky landscape painted in shades of brown and gold. He thought the work in central Turkey could fill a void in the Medieval Logistics Project, an international collaboration that examines systems of roads, communication, and support for traveling armies in Europe and the Middle East from the fifth century to the 12th century. Haldon’s interest in logistics grew from a healthy skepticism about the statistics quoted by medieval chroniclers. When he would read, for instance, about an army of 60,000 men marching across the Anatolian plateau, he wondered whether the region’s modest crops could provide enough food for so many travelers. In many cases, the answer is no. Chroniclers routinely inflated or deflated numbers to enhance their stories. Archaeology and environmental science supplement the written sources, helping historians understand how societies evolved.

In 2005, Haldon asked Elton to scout Beyözü as a possible focal point for a new project, and the two professors made a more thorough exploration in 2006. They quickly realized the village’s potential as an archaeological site when they spotted Greek epigraphs from the Byzantine period embedded in the wall of a building alongside the main thoroughfare. Nestled between hills, the town is relatively small, as it was in ancient and medieval times, and the surrounding fields, mostly used for grazing or growing grain, are accessible for field-walking surveys in the summer months. Princeton’s departments of history, Near Eastern studies, and art and archaeology provided funding to launch the project, and in August and September of 2007, Haldon, Elton, Newhard, and about 20 others came to Avkat for a two-and-a-half week field season, laying the foundation for this year’s work.

The 2008 Avkat team included about 40 professors, students, and field specialists, and when PAW visited the project in early July, work was just getting under way. Joining Haldon were three Princeton graduate students: Zack Chitwood, a third-year student concentrating in Byzantine history; Mark de Groh, a third-year student whose work focuses on the Balkans in the Ottoman period; and Sara Brooks, who studies early modern Europe and plans to complete her dissertation this fall. Brooks would spend much of the season speaking with villagers to document artifacts within Beyözü; her work would help the project leaders to deduce the locations of churches and cemeteries.

Of the Princeton students, Chitwood was the lone returning member from the 2007 field team. That was his first trip to the Middle East, and most of what he knew about archaeology had been absorbed from Indiana Jones movies. Real-life archaeology does have an “aura of discovery,” he says, recalling the first time that he read the medieval Greek characters on a Byzantine tombstone. And the working conditions have not been quite as harsh as he’d expected. Instead of relying on tents, sleeping bags, and camp stoves, Chitwood and his teammates settled into a brick-walled dormitory in Mecitözü, a 10-minute drive from Beyözü, with bunk beds, a cafeteria, a temporary computer lab, and — perhaps most important — hot showers. (Most archaeological projects, Haldon is quick to note, do not have it so good.)

During the summer, while Haldon, Elton, and Newhard analyze data to decide which sites are worth exploring in detail or follow new leads with trips like the one to Kozören, the students from Princeton, Trent, Charleston, and a few other institutions spend most of their time field walking, intending to survey all areas within an eight-hour walk of Beyözü. Each morning, the teams are assigned fields in the area. Using a GPS device and a compass, the students line up at 15-meter intervals and walk in parallel lines, collecting any shards within an arm’s length on either side. Rain and melting snow shift the soils in the spring, and farmers till their fields soon after, Haldon says, so “very ancient things are revealed quite frequently.” Every 15 meters, the walkers pause to mark what they have found in that stretch. The data then are used to create a rough 15-meter-by-15-meter grid that shows the concentration of shards and serves as an estimate of population patterns.

With a year of fieldwork under his belt, Chitwood has been chosen to lead one of this summer’s field-walking teams. The job is pretty straightforward: Line up the grid for five or six walkers, mark each survey unit on a satellite map in a hand-held computer, and carry a few other high-tech tools for the team, including a GPS device to confirm coordinates and a digital camera to document finds that cannot be lifted from the soil. (The team-member kit, by comparison, is low-tech: a compass, a clipboard, some pens, and a spring-loaded “clicker” to count artifacts.) When the team stops to rest on slow mornings, Chitwood draws on his knowledge of the Byzantine Empire to keep the students intellectually stimulated. He explains, for example, what the medieval chroniclers wrote about crops in the region, and shares tidbits from the story of Theodore the Recruit, an illustrious soldier whose exploits are said to include slaying a dragon.

At the end of each day of field walking, the team members turn in papers that tally their artifact finds in each 15-meter segment. Within a few hours, those numbers are entered into the database of the project’s Geographic Information System, or GIS, which can present the information in color-coded maps and other useful formats. It is, Newhard says, one of the simple pleasures of modern archaeology. Work that once was reserved for the months after returning from the field is now done on-site, enabling professors and graduate students to analyze what they are finding almost immediately. “I don’t know how they functioned before GIS and databases and all the tools we’re using today,” Newhard says.

Field walking is the grunt work of survey archaeology, and it requires attentiveness, a quality that tends to fade in the dry heat of central Turkey. Walking through the rural landscape also can mean occasional encounters with snakes, scorpions, and overprotective dogs. But the job has perks — breathtaking views (when you’re not looking at the ground), camaraderie, and the chance to hold artifacts in the palm of your hand. The students tend to focus on the positives.

De Groh is among the most optimistic of field walkers. Tall and thin with an easy smile, he enthusiastically volunteered to wash the dirt off shards and roof tiles on the project’s first afternoon. “My hands smell like thousand-year-old pottery,” he said later, as he relaxed on the porch of the Mecitözü dorm. “I like that.” De Groh had few illusions about the work to be done in Avkat. Before leaving Princeton, he sat in a local coffee shop and listed his expectations: hard work, sore feet, and dry, searing heat, “like Las Vegas.” But that’s why he signed up. There will be plenty of summers in the library in years to come, he reasoned. This was a chance to get his hands dirty.

Historians are supposed to love books and manuscripts (“the dustier the better,” de Groh jokes), and the three Princeton students fit that description. But they also say that being fluent in other areas is critical in a field that increasingly relies on combining information from several disciplines. “Everything has to be collaborative,” Chitwood says. “We know just so much, and no one can know everything.”

At Avkat, Chitwood and his colleagues are exposed to the basics of archaeology, such as the terminology and methodology. They meet international experts who use high-tech tools to supplement historical studies, including Steve Wilkes of the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, the leader of the geophysics team, and Warren Eastwood, also from Birmingham, who studies environmental history. Science can be a powerful corroborator for today’s historical studies. In 2007, for example, Eastwood, Haldon, and three colleagues published a paper that used data from layers of sediment extracted from a dry lakebed about 150 miles south of Beyözü. The sediment included pollens, charcoal, and other particles that provided evidence of agricultural and weather patterns over time. The authors characterized land use in four distinct phases, from the early Byzantine era through the 19th century, and found that the pollen data and the historical record showed “remarkably close agreement” in the timing of landscape changes.

Haldon has combed through satellite images to find similar lakes or lakebeds near Avkat, but so far, the search has yielded no leads. He was able to find a cave nearby, however, and Eastwood came to the site in July to examine the cave’s walls, stalactites, and stalagmites for calcite samples, potentially valuable sources of environmental data.

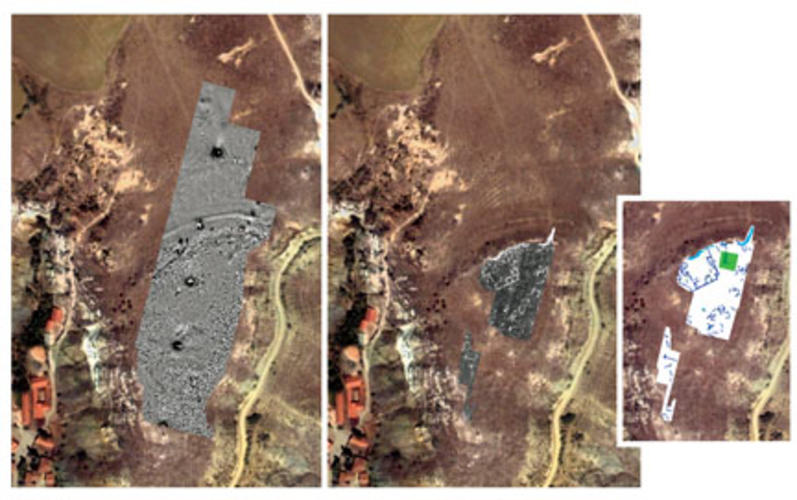

While pollen and calcite studies are relatively new additions to archaeology, geophysics tools like magnetometry and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) have become quite common. GPR, which uses radio waves, can detect buried architecture, such as foundations and walls. Measuring patterns of magnetism can identify ditches and other patterns beneath the soil, adding clarity to the images produced by GPR. These two techniques have produced intriguing underground maps of two notable sites at Avkat. In 2007, the geophysics team surveyed Kale Tepe, or “castle hill,” on the edge of Beyözü and identified what appear to be the buried walls and defensive ditches of a medieval fortress. This summer, on Kabak Tepesi, a hill where field walkers collected early Bronze Age and late Iron Age artifacts a year ago, the geophysicists located features that appear to be storage pits, a defensive bank, and a double-ring ditch outlining the hill’s perimeter — signs of a fortified settlement that may date back 3,000 years. In three years, when the team is permitted to dig, it will have at least two interesting options from which to choose.

On the surface, the 2008 season revealed several interesting finds in and around Beyözü. The village survey team cataloged three inscribed Byzantine tombstones, fragments from a glass bracelet and a glass lamp, a few Byzantine coins, limestone blocks from a paved street, stone water channels and pipes, and pieces of a marble column. The field-walking teams covered 622 hectares (2.4 square miles) in areas north and south of Beyözü. In addition to documenting pottery finds, they spotted remains of what may have been two Byzantine watchtowers and a rock outcropping with a flattened central platform, possibly an ancient altar.

With less than two months of fieldwork to draw from, the Avkat team has not reached any firm conclusions, but Elton listed a few preliminary observations in an early draft of the project report for this summer’s work. Based on the concentrations of shards found in fields near the village, the ancient residents of Avkat probably settled in small towns with occasional farmsteads between the towns. And much like their modern counterparts, they relied on cereal crops to make bread and feed livestock. In the coming months, Haldon, Elton, and other senior team members will examine the 2008 finds and pose new questions as they plan next summer’s work.

Haldon’s role in the process is primarily analytical, so he does not need to be on-site at all times. This summer, he left Avkat for part of July to work on a book project with a colleague, and on the ride back to Ankara, still clad in dusty jeans and boots, he seemed to miss the field already, talking about the team he had assembled and wondering aloud about what the geophysicists might find in their survey. Haldon has been a historian for more than three decades, but in his undergraduate days, he considered a career in field archaeology — a fact that shines through each time he climbs over barbed wire to get a closer look at a piece of Byzantine construction or navigates a tight turn on a steep slope in a four-wheel-drive truck.

“The whole thing is an adventure,” Haldon says. “It’s serious scholarship and it’s an adventure. You can’t do much better than that in life.”

1 Response

Alan W. Lukens ’46

10 Years AgoPrinceton and Turkey

Princetonians’ roots and attachment to Turkey (cover story, Sept. 24) go way back to the early missionaries of the 19th and 20th centuries. Many of these missionaries were teachers at Robert College in Istanbul, which was, for many years, the only English-language university in Turkey.

Early in World War II, when the possibility existed that American forces could enter Europe through Turkey, the Sultan’s granddaughter, Princess Hümeyra Özbas, came to Princeton to teach Turkish to American officers. She had been exiled to Egypt along with members of the royal Ottoman family at the beginning of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. Once there was no longer a need to teach American officers Turkish, she remained at Princeton to teach English to Turkish pilots. I believe she was one of the first female instructors at Princeton.

During the 1950s, under Professor Philip Hitti, Princeton became one of the major American universities with a Turkish language and area-studies program, and a number of midcareer Foreign Service officers were sent there for a year by the State Department.

Later, Ahmet Ertegun, son of Turkey’s wartime ambassador in Washington, made a fortune with Atlantic Records. He spotted Princeton as the best place to endow a chair of Turkish studies. Currently, Professor Heath Lowry is the Atatürk Professor of Ottoman and Modern Turkish Studies, and Professor M. Sükrü Haniolu is the chairman of the Department of Near Eastern Studies. Thanks to Princeton’s initiative and support of this Turkish program, there are now about 15 Turkish undergraduates and 15 graduate students at the University.

“Princeton in the nation’s service and in the service of all nations” certainly applies to this innovative Turkish program. I served in Turkey from 1951–53 and am once again involved.