Math Versus Politics

A Princeton neuroscientist fights partisan gerrymandering — with statistics

The founders of our country did a pretty good job setting up the first constitutional democracy, says Princeton professor Sam Wang. But like so many complex systems, ours has a bug: an open invitation to partisan manipulation that can produce extreme mismatches between voter preferences and electoral outcomes.

As a neuroscientist and professor of molecular biology, Wang draws on his expertise in math and statistics to study brain development, learning mechanisms, and the causes of autism. But these days, he says, he spends just as much time working to fix that constitutional bug — partisan gerrymandering, the practice of mapping state electoral districts in ways that maximize one political party’s advantage over the other.

Gerrymandering is “a flaw in our electoral system that the founders didn’t envision,” Wang says. “The ability of legislators to draw their own district boundaries is a loophole in democracy.”

On Oct. 3, the U.S. Supreme Court was to hear oral arguments in what experts consider the most important partisan gerrymandering case in decades: Gill v. Whitford, which argues that Republican efforts to gain a political edge so skewed Wisconsin’s 2011 state legislative map that the results unconstitutionally infringe on voters’ rights to express their political preferences. Wisconsin Republicans hold nearly two-thirds of the seats in the state assembly, even though Democrats won almost half the statewide vote in the last election.

Wang’s work on partisan gerrymandering did not play a role in earlier stages of the case. But he has co-authored a friend-of-the-court brief discussing three statistical tests he developed to detect the existence of skewed electoral outcomes and assess how likely it is that such results arose by chance, rather than via partisan manipulation. Supreme Court justices could draw on that brief as they consider their ruling.

“There are a lot of ways in which I as a citizen have relatively little to say about policy, but gerrymandering is a domain in which it’s possible for my skill set to be useful in making government and society work a little bit better,” Wang says. “It’s a way in which I have a special contribution to make.”

Wang has publicized his statistical tools both in scholarly journals and in newspaper op-eds aiming to explain gerrymandering to a wider audience. (“Let Math Save Our Democracy,” urged the headline over a 2015 New York Times piece.) And the website of his Princeton Gerrymandering Project — gerrymander.princeton.edu — allows judges, lawyers, and ordinary citizens to see how their states stack up against Wang’s measures of partisan gerrymandering. “If activists would like to achieve reform, it might be nice for them to have these statistical tools at their fingertips,” he says.

Although Wang’s natural-sciences specialty is unusual for an election-law scholar, that eclecticism places him squarely in a venerable American tradition, says Edward B. Foley, a constitutional law professor who directs the election-law program at Ohio State University’s law school. Thomas Jefferson was a writer, architect, and politician; Benjamin Franklin was both statesman and scientist. “The founders respected so-called Renaissance men,” Foley says.

In his own field, Wang has tried his hand at communicating complex ideas to laypeople, co-authoring well-regarded books for general readers on brain science and child development. Julian Zelizer, a Princeton history professor who co-hosts a weekly politics podcast with Wang, praises him for his humor, his modesty, and his wide-ranging interests.

“He’s able to straddle both worlds,” Zelizer says. “He’s a numbers person and a scientist who’s just a great people person, which isn’t always the case.”

Wang’s interest in gerrymandering grew out of his forays into political analysis over the past four presidential-election cycles, as — under the banner of the Princeton Election Consortium — he aggregated polling data to predict election outcomes with sometimes uncanny accuracy. (After drawing less accurate conclusions about the results of last November’s presidential election, Wang gulped down a slimy morsel of raw cricket on national TV, fulfilling a tweeted promise to “eat a bug” if Donald Trump won more than 240 Electoral College votes.)

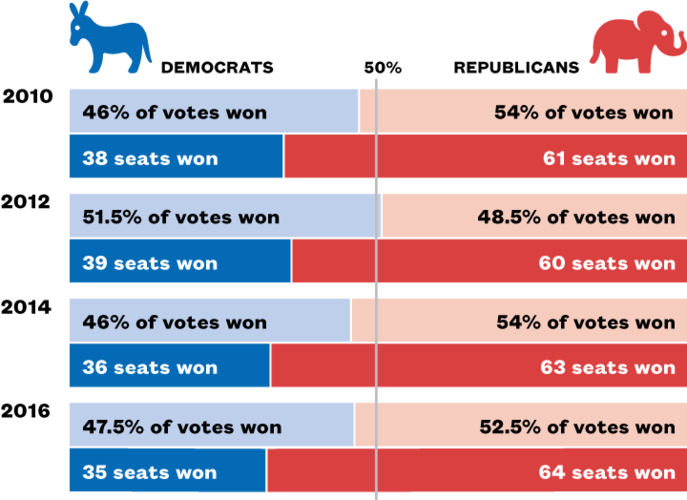

The gerrymandering case before the U.S. Supreme Court centers on WISCONSIN STATE ASSEMBLY districts. In the 2010 election, before redistricting, Republicans won the popular vote by an 8-point margin, taking 61 of 99 Assembly seats. By 2016, the GOP had control of three more seats despite winning a slightly smaller share of the popular vote.

In the 2012 election, Wang correctly predicted that Democratic candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives would receive more votes than Republicans nationwide — but he failed to foresee that Republicans would retain control of the House anyway. How had his polling analysis gone wrong? he wondered.

The answer, Wang and other analysts concluded, was gerrymandering: In the 2010 election, Republicans had gained full control of an unusually large number of state governments, just in time to control the redistricting process that followed the 2010 census. The party used that power to draw advantageous district maps that gave its candidates an edge in later elections.

Historically, Democrats have been just as likely as Republicans to gerrymander — the Democratic gerrymander in 1980s California is legendary, and a case involving Maryland’s 2011 Democratic gerrymander is making its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. “No political party has a monopoly on greed when it comes to gerrymandering,” says Richard H. Pildes ’79, a professor of constitutional law at the New York University School of Law.

In the most recent round of redistricting, Republicans simply had more scope for their partisan greed, experts say. “If you’d given Democrats control of Wisconsin, North Carolina, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Florida, etc., in 2011, we’d now be talking about the plague of Democratic gerrymandering,” says Nicholas Stephanopoulos, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School who represents the plaintiffs in the Wisconsin case. Other developments magnified the impact of the 2010 gerrymander, experts say. These days, citizens reliably vote their party affiliations, splitting their tickets far less often than in the past, so a district with a solid majority of voters from one party is likely to elect that party’s candidates year after year. And powerful computer technology now permits redistricters to calibrate district lines with ever-increasing precision.

“It used to be the mapmakers had the mathematical equivalent of muskets,” says Foley, of Ohio State. “Now they’ve got nuclear weapons.”

Gerrymandering matters because, taken to an extreme, it breaks the link between what voters want and who their representatives are, legal and political experts say. “At its most basic level, a democratic system is supposed to be responsive to the preferences of the voters,” says NYU’s Pildes. “If districts are willfully manipulated for certain sorts of partisan ends, you can get legislative bodies that are not actually responsive to the preferences of the majority.”

In districts that are safe for one party or the other, incumbents have no incentive to listen to opposition voices or to moderate their positions in an effort to win over the other side. The result can be polarized political positions that make it harder to compromise over legislation. And without intervention, lawyers and political scientists say, gerrymandering is likely to become more and more extreme.

“If there’s not action taken on this in the courts, you’re just going to see an arms race of Democrats and Republicans building districts that are as safe as possible, that do not flip” between censuses, says Brian Remlinger, Wang’s research assistant on the Princeton Gerrymandering Project. “You have an election every two years, but it’s going to be the equivalent of having an election every 10 years. And that election you have every decade is still going to be rigged.”

Analysts disagree about how large a role gerrymandering plays in giving Republicans an edge in the battle for control of Congress and the states. Gerrymandering is irrelevant to U.S. Senate elections, which are conducted statewide, not within individual districts. And even in state legislative and U.S. House elections, where district lines do matter, many political scientists think that political geography — the tendency of Democrats to live in densely populated city districts, diluting the effectiveness of their votes, while Republicans are spread out among a greater number of far-flung rural districts — plays a more significant role.

But Wang disagrees. In the 2012 congressional election, “the effects of partisan redistricting exceeded the amount of asymmetry caused by natural patterns of population,” he wrote in a 2016 article in the Stanford Law Review. “Redistricting in a handful of states can generate a greater deviation from symmetry than population clustering in all 50 states combined.”

According to his calculations, in 2012, partisan gerrymandering in just nine states gave Republicans 28 extra seats, compared with six for Democrats — a pro-Republican swing of 22 seats, in a year when the Republicans’ House majority totaled only 33. Absent gerrymandering, Wang argues, the Democrats might have had an outside chance of gaining control of the House, allowing President Barack Obama to start his second term with a Democratic Congress, rather than a divided one.

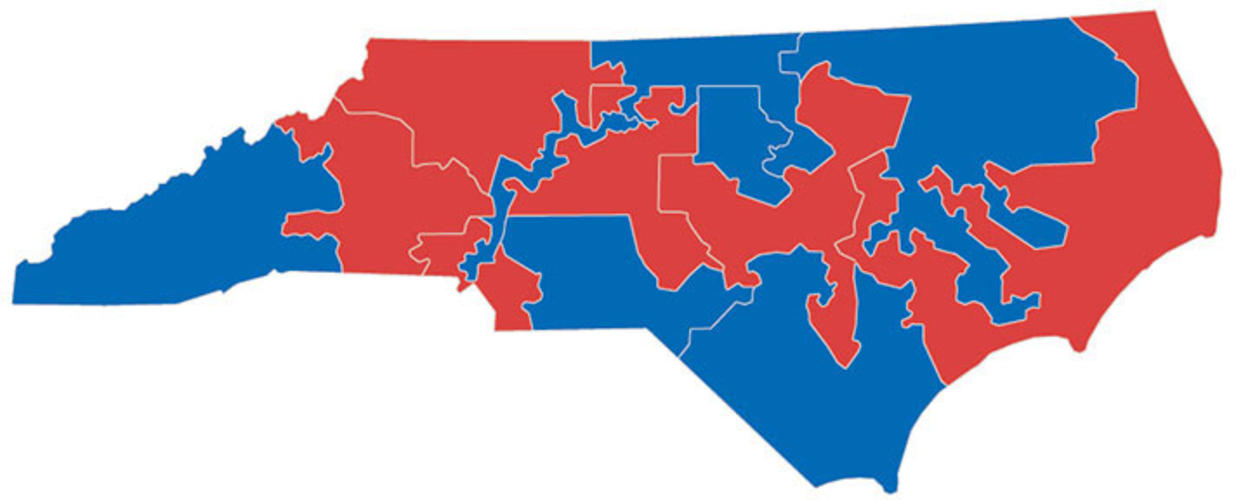

NORTH CAROLINA CONGRESSIONAL MAP AFTER 2010 ELECTION (BEFORE REDISTRICTING) Republicans made big gains in the North Carolina state legislature in 2010, putting them in control of congressional redistricting.

NORTH CAROLINA CONGRESSIONAL MAP AFTER 2012 ELECTION (AFTER REDISTRICTING) In the 2012 congressional election, Democrats won a slight majority of the popular vote — but only four of the 13 seats. Results were similar in 2014 and 2016.

Wang’s statistical test suggests this could not have happened by chance if districts were drawn fairly. In May, the Supreme Court struck down two of the North Carolina districts, saying lawmakers had relied too heavily on race when drawing them up.

The practice of gerrymandering dates back to the 18th century, although the word itself is newer: A political cartoonist coined the term in 1812, to describe a salamander-shaped state senate district created by the Massachusetts legislature to improve the fortunes of Gov. Elbridge Gerry’s political party.

Historically, the courts have stayed out of redistricting battles, except to strike down gerrymanders intended to dilute the voting power of racial minorities. In a 2004 case concerning partisan gerrymandering, four conservative Supreme Court justices argued that judges would never be able to decide when acceptable levels of political influence on the redistricting process morphed into gerrymandering so egregious as to be unconstitutional. Four liberal justices disagreed, but they did not converge on a single standard for making that determination. Justice Anthony Kennedy, frequently the court’s swing vote, staked out a middle position, saying that a workable test for excessive gerrymandering might exist someday but that he hadn’t seen it yet.

Political scientists and election-law experts have been trying ever since to come up with a statistical test that will satisfy Kennedy. The Wisconsin case revolves around one such test, developed by Eric McGhee, a political scientist with the Public Policy Institute of California, and Stephanopoulos, the University of Chicago law professor.

Wang’s combination of deep mathematical expertise and an accessible explanatory style makes his work valuable, say some experts in the field. “Although Professor Wang can play in the deep end of the math pool, he can also swim in the shallow end, and he can move back and forth with versatility,” says Foley, of Ohio State. “And that’s very useful, because the judges are all going to be in the shallow end.”

Wang’s three statistical tests (sidebar, page 32) are “a really helpful set of tools,” says Barry Burden, a political scientist who directs the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “We’re all grappling with what threshold to set for what is acceptable partisan politics and what is unacceptable, unconstitutional behavior, and the Supreme Court is also looking for that standard.”

But not everyone agrees that Wang’s work, however well-presented, has broken new ground. “Each of his individual pieces is a variation on things that other people have already proposed,” says McGhee, the co-creator of the statistical test at the heart of the Wisconsin case. “There’s almost nothing that is completely new there.”

Whatever its mathematical originality, Wang’s ability to popularize the sometimes arcane topic of gerrymandering gives his work added importance, say some in the field.

“It is useful to have the public learning about this,” says Stephanopoulos. “Judicial action is one possible way to address these issues, but public policy and legislative action is another way. If there’s ever going to be action by Congress or action by the states, it’s really important for more people to be thinking and talking about these issues.”

What role Wang’s work will play in the case before the Supreme Court remains unclear. Friend-of-the-court briefs — including the one co-authored by Wang; Yale Law School Dean Heather Gerken ’91, an election-law expert; and three others — likely will expose the justices to a variety of statistical tests for gerrymandering, in addition to the test developed by McGhee and Stephanopoulos and featured in the plaintiffs’ case. One scholar recently described the parade of options aimed at winning over the court’s swing voter as “Justice Kennedy’s beauty pageant.”

But offering too large and disparate a menu of choices could backfire, some warn, giving the court’s conservatives “more ammunition to say, ‘Well, look, there are endless standards and none of them is right, so we’re going to throw up our hands about all of this,’” says Burden, of Wisconsin-Madison.

A Supreme Court ruling striking down Wisconsin’s state legislative map would reverberate far beyond that state’s borders, election-law experts note. For the first time, “every redistricting going forward will be one in which the redistricters will have to be concerned about whether the plan will be held to be an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander,” says Pildes of NYU. “It would be a significant deterrent, I think, because redistricters don’t like to lose control over the districting process to the courts.”

Ultimately, that could encourage more legislatures to follow the lead of states like Arizona and California, which have taken the job of redistricting away from elected politicians and put it in the hands of bipartisan or nonpartisan commissions charged with drawing maps that treat both political parties equally, Pildes says.

How significantly a reduction in gerrymandering would change the polarized and dysfunctional nature of contemporary American politics is a matter of some dispute. For Wang, partisan gerrymandering is “near the top of the list” of problems facing American democracy, as he and Remlinger wrote last spring in the Los Angeles Times.

Others are not so sure. “I don’t think changing redistricting is going to fix everything in American politics; it’s not going to fix most of the things in American politics,” says Burden. “But it will fix some, and we already have models for doing that in some states and in other parts of the world. So why not adopt them?”

Wang was a Democrat when he began his research into politics —– the day after speaking with PAW for this story, he emailed to announce that he had re-registered as an independent — but reducing the impact of gerrymandering will help all voters, regardless of political affiliation, he says.

Although Republicans currently benefit more from gerrymandering, “there are demographic changes coming, and some of these states that are currently close are moving in the direction of Democrats,” Wang says. “As those states shift, the party that is hurt by gerrymandering will become the Republican Party. And when that day comes, they’re going to be grateful that some pointy-headed academic rectified this offense.”

Deborah Yaffe is a freelance writer based in Princeton Junction, N.J. Her most recent book is Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom.

How Wang’s Tests Work

In his three statistical tests for gerrymandering, Princeton neuroscientist Sam Wang draws on the concept of partisan symmetry: the notion that, in a non-gerrymandered electoral system, if the two parties swap vote shares, they should also swap their share of seats won.

Wang’s tests are designed to assess whether deviations from this symmetry could have arisen by chance or, instead, suggest partisan bias at work.

Examples are from Pennsylvania’s

2016 election. (R) = Republicans, (D) = Democrats

The first test, which Wang calls the LOPSIDED-WINS TEST, looks at electoral districts won by each party and compares the two parties’ average margins of victory, using common statistical techniques to determine whether any difference between those averages could be attributable to chance. A party that consistently wins its seats by lopsidedly big margins — as opposed to smaller, more efficient ones — is likely the victim of a gerrymandering technique known as “packing”: Its voters have been crammed into a small number of districts, where they can elect relatively few representatives.

Example:

(R) won their districts with an average 63.8% of the vote

(D) won their districts with an average of 75.1% of the vote

The second test, the CONSISTENT-ADVANTAGE TEST, ranks each party’s share of the vote in the state’s electoral districts and computes both the median (the middle value in the list) and the mean (the average). A party whose average vote share is significantly larger than its median vote share also is probably a victim of packing: Its voters show up in overall totals but have relatively little impact district by district.

Example:

(D) median vote share: 40%

(D) average vote share: 47%

The third test, the EXCESS-SEATS TEST, uses computer simulations to gauge whether one party’s share of seats won deviates unexpectedly from national norms. Drawing on actual nationwide election results, the computer randomly generates many combinations of electoral districts, drawn from states across the country, that match the targeted state’s districts in partisan composition. Then the average number of seats each party wins in these simulations is compared with the actual results in the targeted state.

This test can gauge whether political geography — voters’ tendency to sort themselves into like-minded enclaves, with Democrats clustering in cities and Republicans spreading out across rural areas — is enough to account for an election’s outcome, or if the results are so anomalous that they suggest gerrymandering at work.

Example:

(D) won 5 of 18 seats with 45.6% of statewide vote

Simulations indicate that, according to nationwide trends, (D) would be expected to win 7 or 8 seats.

All Pennsylvania tests indicate possible gerrymandering in favor of Republicans. Test your own state at gerrymander.princeton.edu.

Source: gerrymander.princeton.edu

Video: Gerrymandering — A Tutorial

Courtesy Princeton Gerrymandering Project

9 Responses

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoYes, gerrymandering is...

Yes, gerrymandering is undemocratic. But it also reveals why democracy is undemocratic. The idea that democracy somehow is more representative than oligarchy, aristocracy, or some other system is false. Democracy gives one the impression -- a very false one indeed -- that somehow one-man/woman one-vote can make a system really representative. This ignores the role of money, the role of mental incapacity, the differences between voters and their motivations, their sense of what their real interests are, and many other factors. Gerrymandering is simply one way -- a very visible one -- of undermining democracy by practicing it. There is really no solution to this problem. Even a construction of electoral districts strictly along what look like objective mathematical criteria cannot really make elections more representative. The rich will always have in effect more votes than the poor, the dead will always vote in heavy numbers, and those who stay home will thereby also vote. I think Plato would agree with me.

Michael Otten ’63

8 Years AgoFixing an Election Loophole

While I am delighted by the thoughtful analyses in the Oct. 4 feature that demonstrate that “the ability of legislators to draw their own district boundaries is a loophole in democracy,” I am even happier to see that some academics are building tools (e.g., Professor Sam Wang’s models) and making recommendations to fix (pardon the double entendre) the political system. Harvard University professor Michael Porter ’69 has done an analysis of the duopoly resulting from the constitutional loophole and proposed remedies that seem quite timely, challenging, and possibly achievable. The first step he proposes in his report, “Why Competition in the Politics Industry Is Failing America,” is to accelerate the use of nonpartisan primaries, which allow any registered voter to vote for any candidate in a primary, regardless of party affiliation (or nonaffiliation). Then ranked-choice voting (being battled over by entrenched legislators in Maine) ensures that every voter’s vote counts, even if a voter’s first choice is eliminated by gaining too few votes, thus avoiding the so-called “spoiler effect.” Moving in this direction should refocus politicians on finding nonpartisan solutions, as that is the only way they will gain the support of the 40-plus percent of voters who are now disavowing any party affiliation (per a recent Gallup Poll). There are groups of alumni in various locations beginning to coalesce behind this movement – this is a loophole that needs to be filled!

Walter Weber ’81

8 Years AgoTaking Issue with a Congressional Election Plan

Published online Jan. 4, 2018

To address gerrymandering, James Cunningham ’73 recommends having members of Congress elected on a statewide basis rather than a district-wide basis (Inbox, Nov. 8). He says it would be “[s]imple, clear, sensible, incorruptible” and "true and effective democracy for America.” I disagree.

Yes, this system would be simple and clear. But sensible? Instead of having representatives elected by voters from the local geographic region they represent, they would be elected statewide by voters in the largest population centers, i.e., the big cities. For example, the numerous voters of Philadelphia (and New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Phoenix, etc.) would choose all of the representatives for their state, leaving residents of the less populous regions with no effective say. Incorruptible? If there is ballot fraud in Chicago or some other metropolis (perish the thought!), under Cunningham’s proposal it would infect the entire state, not just Chicago.

“True and effective democracy for America”? Why should Cunningham stop at abolishing congressional districts? Why not have all the members of both the House and Senate elected by the entire U.S. population, “first-past-the-post”? That way temporary mass sentiment could uniformly dictate the identity of all election winners throughout the country, not just those in places most swayed by current trends.

Finally, Cunningham sees his proposal as the solution to the power of political parties to narrow the choice of candidates. But how is this so? If the parties select the candidates for statewide Senate races, why would they not do the same for statewide House seats? Wouldn’t this leave Cunningham’s “centrist nonpartisan majority” even less able to muster the money and manpower to put forward their preferred candidates?

Rob Slocum ’71

8 Years AgoGerrymandering? Not Here

Your article on gerrymandering (feature, Oct. 4) might have been stronger if it had drawn on the experiences of non-gerrymandered states. There are more than you think. Not only do Arizona and California use nonpartisan methods for districting, but Iowa has done so at least since the ’70s. There are also seven states with only one district (Arkansas, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming).

Let me stipulate that gerrymandering is nuts, but I thought the story might have also had an entertaining sentence or two about how this issue has somehow gained traction at a time when “Republicans dominate state legislatures at a rate not seen since the Civil War” (Daily Kos, Nov. 14, 2016).

James Cunningham ’73

8 Years AgoPaths to Fairer Voting

To get rid of gerrymandering (feature, Oct. 4), abolish voting districts!

Gerrymandering is at the root of the domination of American politics by the extremes of Right and Left. With the real choice made by party activists in the primaries, the sensible voter in the center is left at the election without a viable choice and is in essence disenfranchised. The centrist nonpartisan majority is consistently identified in polls, but is not represented in Washington: It is politically silenced. That is undemocratic.

Even depoliticized redistricting, such as that pioneered by former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in California and supported by Dr. Sam Wang’s models, will not cure the problem. As people of like minds tend to live in the same areas, “safe” seats will endure and party ideologues will continue to dominate the nomination process.

In this age of social media, electoral districts are obsolete. Champions of particular causes, from gay rights to balanced budgets, can and should mobilize their constituencies, wherever in a state they may live. Without districts, the two Senate candidates with the most votes and however many representatives the state is entitled to by the latest census would go to Washington in a first-past-the-post system. Simple, clear, sensible, incorruptible.

This would be true and effective democracy for America.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoWhat does fairer voting...

What does fairer voting really mean? Most of our elections from 1796 on have been disputed, nationally and probably in most localities. I personally remember, of course, 1960, when the victory of JFK was accomplished with deceased voters in Chicago. I remember 2000 when the Supreme Court decided it was really Supreme. And then there is 2016, when with Russian help Donald Trump, not even qualified as a dogcatcher, managed to pervert the process to enter the OVAL OFFICE.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoIt was long believed that...

It was long believed that single-member voting districts were best since with proportional representation a myriad of parties and groups would have to negotiate coalition governments, the pattern in Europe, especially France and Italy, which certainly did not lead to what anyone would call democracy. Democracy itself, the idea that people should make political decisions indirectly by electing representatives, is a very flawed process. Direct democracy would be better but is impossible except in a small city state, none of which would in fact today be small enough. The problem is simply that with any political system, indirect democracy, aristocracy, oligarchy, etc. no form of democracy can really work. The French reactionary and anti-Dreyfusard, Charles Maurras, a hundred years ago said that when you abolish aristocracy you don't get democracy, you get oligarchy. Is this not exactly what we get in America: Whether ruled by Democrats or Republicans, we are really ruled by Wall Street, the military-industrial complex, and the prejudices of the average American redneck. A real choice is between an intelligent aristocrat like Pericles or a nitwit plutocrat like Donald Trump.

Clark Cohen ’86

8 Years AgoPaths to Fairer Voting

Unfortunately, the problem is far worse than gerrymandering by itself. Even if district lines were drawn perfectly (whatever that means), 51 percent of the vote would win 100 percent of the representation. Those 49 percent wasted votes do not amount to “consent of the governed.” Today’s harmful winner-take-all dynamic comes rather from the fact of single-member districts — i.e., one representative per geographic district. A better solution is to combine together single-member districts into larger multi-winner districts as would be enacted by the newly introduced bill H.R. 3057. Gerrymandering would simply go away, as would most of the problematic district lines. A timely read is nonpartisan FairVote.org’s amicus brief for the Supreme Court regarding the current case on gerrymandering: http://bit.ly/fairvotebrief.

(comment via Facebook)

Frank Henry

8 Years AgoFull Voting Rights

The first bridge we need to cross is granting the voters in

our fine country their "32 Full Voting Rights." Our country

is some 241 years old, and NO voter has these rights yet!

Sam, your approach of concern (or work) toward the two

party "balance" (or t-test) to determine if deliberate

"gerrymandering" is present in our political districts should be

placed on the back burner (with the burner turned off). The

focus on just the two parties is directly related to the fact that

the Dems and Repubs have over many years garnered

unconstitutional power and control in making election laws

(fed, state, local) and also our general laws (fed, state, local).

Under our 32 Full Voting Rights, the first focus on drawing

district maps is to make sure there shall be an equal number of

US citizens age 18 and up whose voting rights have not been

suspended....and no other criteria!!!

Thanks and good luck, Frank Henry, Full Voting Rights

Advocate, Tel: 928-649-0249, e-mail: fmhenry4@netzero.com