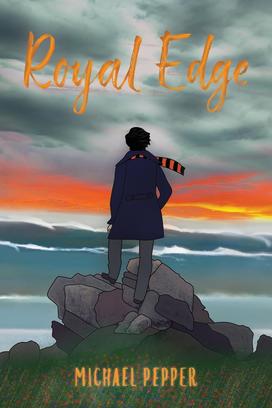

Michael Pepper ’71 Tells the Story of a Unique Friendship in New Book

The book: Royal Edge (self-published) tells the story of Michael and Ella, an odd pair that form a unique friendship. Michael is a recent graduate of Princeton and Ella is an elderly woman who lives in town and is in need of a roommate. Logically, Michael takes her up on the offer and begins to learn a great deal about Ella’s past as a Russian countess. Royal Edge tells the true story of Pepper's post-Princeton experience. It explores a variety of themes including friendship, coming-of-age and discovering what one wants to do, as well as learning to embrace all that life has to offer, especially in times of uncertainty.

The author: Michael Pepper ’71 earned his undergraduate degree from Princeton University in architecture and urban planning. He went on to work in architecture, and helped to develop many skyscrapers throughout his career. He also taught Real Estate Development at Kellogg and Booth Graduate Schools of Business.

Excerpt:

Prologue: P-rade

I don’t see myself as being the hero here. But I may have undergone a somewhat noble transformation just steps outside the wrought-iron FitzRandolph Gate at the entrance to Princeton University.

In May of 1971, nearly 800 of us graduated, officially, as princes. Another 37 were women—all transfers, among the first to be admitted. I was the first in my family to leave home for college; higher education was not my birthright and my parents were indeed very proud. I had grown up just outside of Chicago and then spent four years at Princeton in an East Coast paradise of art and architecture, training for adulthood on a kind of democratic royal grounds.

Princeton’s campus is articulated by courtyards with enthralling sculptures, walk-through fountains, and archways. Nassau Hall faces the center of town, which used to be a stopover with inns and saloons on the two-day journey by horse between New York and Philly. For over 200 years now, Nassau Hall has stood, set back from the street among towering old sycamores. Where this parklike area meets the street, FitzRandolph Gate opens ceremoniously as new graduates walk off campus, returning to their communities.

I’m back here today for my 51st reunion. It’s late May, and each year at this time, over 25,000 alumni, friends, and family members return to campus. But today, there’s an even larger group, as for the last two years, the coronavirus postponed all commemorations. So the classes of 1970 and ’71 have joined the class of ’72 in honoring our 50th. There’s a fervent sense of rejoicing in the air as we feast on freedom long taken for granted.

Among the highlights of Princeton reunions is the parade, fondly called the P-rade. Marchers in the P-rade boast the college colors. Some classes wear orange-and-black-striped sport coats. Multicultural Princetonians wear orange-and-black traditional garb, like kilts and saris. With costumes and flags, all those preparing to participate first gather on Cannon Green. Then, beginning with the oldest living graduates, typically in golf carts with family members driving, each class moves into the parade line. Those in the carts are often 100 years or older. About half a mile of multi-aged, orange-and-black figures progress along the route, interspersed with marching bands, jugglers, unicyclists — even a man who walks on his hands.

Once I step through the gate, I’m on palatial ground again, moving toward Cannon Green, where rumor once convinced us that our Rutgers football rivals, the oldest rivalry in intercollegiate football, had stolen our ancient cannon. The cannon, a relic from the Revolutionary War, appeared to have been dragged from a dug-out hole nearly six feet deep—rather than buried under the big pile of dirt next to it. At the time we saw what we were led to believe rather than what was really there. Half a century more insightful, I’m now prepared to enter this massive parade.

Many things are going through my mind. The excitement. The presentation I’m giving later. The timelessness of the campus setting. The aging. I find my class and look toward the Old Guard at the front of the line— much fewer in number, and thankfully, still a long way ahead of me—as they start their golf carts.

We march past gothic dorms and lecture halls. We march past laboratories, where research now advances into areas of study not yet conceived in my college days. Parading alumni hold up large placards noting critical events from their years at the university. A diminished cadre toward the front carries WWII signs: D-Day. Hiroshima. Then Korean War veterans. First astronauts in space. The Kennedy assassination. My own class carries signs commemorating our first female classmates, the first man on the moon, marijuana, birth control, and of course, Vietnam. The classes that follow carry signs noting the Chinese peace accords and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Looking toward the Old Guard at the front, I consider that for them, looking back toward the youth, they must see their past and our future. And as I walk in step with the class of 1971, looking up ahead at the Old Guard, I see our past . . . and my future, if I’m lucky enough to make it there.

In all these years, I have barely begun to unravel the year that followed my graduation. Only recently have I started sharing threads with my three daughters while on cross-country hikes. With my girls in mind, I look back to where this year’s graduating class is assembling. Yes, I can see our future there—with nearly half that class female and every color of skin. We form a community not defined by our collective past but redefined by what we each might contribute.

In 1971, many of my classmates chose not to wear their caps and gowns—myself included. Instead, until all hours of the previous night, we stood in the large fountain in front of Wilson School, surrounded by marijuana smoke. It was a bittersweet celebration, as most of the male graduates in my class were subject to the latest draft—the possibility of going to Vietnam.

We each had to carry a draft card at all times that noted our status, which until our last day of enrollment had been “2-S”: student deferred. Within weeks of graduation day, our “1-A” cards would arrive, which stated that we were immediately available for service. And if our Random Sequence Number (RSN) had already been called that year—or soon would be—we would be overseas in months. In the previous draft year, they had gotten all the way through RSN 195. I was RSN 159 .

Most of us had friends who had served in the war. My friend Jim had already died there. At that time, my cousin Kenny was in the Navy on a patrol boat on the Saigon River. I didn’t know if I would be drafted, but I knew I had to find my way in the meantime. To start mapping out a worthwhile career and meaningful personal life, despite what might happen next.

Sure, we had begun to take part in the fight for social justice. Black people, Native Americans, gays, and other marginalized groups were rising up. We were joining anti-war protests, too. Pot, speed, LSD, and mescaline were readily available to float us through the malaise. Birth control pills brought confusing freedom. The Beatles and the Stones stirred an amorphous cocktail of revolution. It was a complicated time for many and more so for a college graduate eligible for the draft. There were many issues to worry about, but none as threatening as losing our student deferral status. Adding to the irony of the draft, until 1971 and the passage of the 26th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, 18 year-old males could be drafted but could not vote until they reached the age of 21.

In his graduation address, the University president noted that if we believed we had learned enough in the past four years to have all the answers going forward, then the University had failed us. That if, instead, we understood our education would continue throughout our lives, we would evolve with our experiences.

Little did I know at that time that an unusual experience awaited me mere blocks away from where my alma mater cast me out . . . to see.

Excerpted from Royal Edge by Michael Pepper ’71. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Reviews:

"Michael Pepper's Royal Edge is a searing and profound memoir that touches on so many subjects. . . . I enjoyed Royal Edge immensely and recommend it to anyone who wants a front seat at one of the most tumultuous times in recent American History.” — Anita Abriel, internationally best-selling author of The Light After the War and The Life She Wanted

"The message of the book has really stuck with me. As Michael so beautifully shows in his book, there's so much we don't know about others, and we need to ask the right questions to understand their point of view." — Jodi Warshaw, founding editor of Lake Union/Amazon Publishing

3 Responses

Henry Lerner ’71

7 Months AgoBrings Back Memories

I just finished reading Royal Edge and enjoyed it immensely. Having lived through those same times, the book brought back many memories — mostly warm and wonderful, some not. While the entire book was a tour de force, I especially loved the last chapter when Pepper distilled the essence of what he learned from Ella. There is a lot there to take to heart.

Throughout the years I’ve been collecting schoolboy and college fiction; the volumes now total more than 800. Twenty-five or so of them are set at Princeton — and I will happily add Royal Edge to that group.

Lamar Oxford ’71

1 Year AgoA Sensitive and Expressive Soul

As one of Mike Pepper’s best friends at Princeton in the late ’60s, I shared extraordinary experiences with him. From opening our minds figuratively thru all-night freshman year conversations about life, God, women, etc., to opening our minds literally with psychedelic trips in sophomore year, we held tight to our deep friendship through those turbulent times.

So his ability now, so many years later, to condense his fascinating experiences the year after our graduation in this marvelous book comes as no surprise to me.

He has been a sensitive and expressive soul since the day I met him in the fall of 1967. Nothing great he ever does will surprise me.

John E. Nathan

1 Year AgoExcellence From an Early Age

As a classmate and teammate from the sixth grade through high school, I knew Michael Pepper as an ambitious and conscientious athlete with unlimited potential for excellence. It came as no surprise his prowess at Princeton, on and off the football field, would shine in all aspects of life ahead. Pleased to read his journal and learn more than superficiality about his maturation and productive years.