Mississippi Eyes

Matt Herron ’53 remembers the summer of 1964, when he led a seminal photography project to capture the story of civil rights in the South

When photographer Matt Herron ’53 arrived with his wife and two children in Birmingham, Ala., on a summer Sunday in 1963, the only thing on his mind was finding a laundromat. The family — headed to Jackson, Miss. — had been driving for days from Philadelphia, and they were tired and dirty.

They found a laundromat. And they found a sign in its plate-glass window that said: “Whites Only.”

Demoralized, they sought a place to cleanse their spirits rather than their clothes, joining the services at the 16th Street Baptist Church. When their 3-year-old daughter had to go potty, his wife took her down to the basement.

Two weeks later, on Sunday, Sept. 15, Herron got a call from Life magazine. A bomb had been placed in that very basement, and four little girls were killed. Herron returned to the 16th Street Baptist Church to take photographs.

Guided by deep passions about civil justice, Herron had gone to Mississippi to document a “manner of life” — Southern culture and Southern institutions. “What I really wanted,” he says, “was to start a documentary photography team.” He saw his moment in the spring of 1964, when plans were forming to bring 1,000 college students to Mississippi to teach and to register black voters: Freedom Summer.

He went to New York, raised $10,000, and received the blessing of Dorothea Lange, the documentary photographer who had captured some of the most enduring images of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression. Then he recruited eight photographers, and settled on a name: the Southern Documentary Project. The team fanned out across Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, seeking images that captured life in hidden corners, and revealed the flashpoints of a national crisis.

The photos cover the mundane as well as the momentous: the playfulness of coeds shaving their legs at an outdoor well, the subversive mischief of a plumber with a garden filled with overgrown jukeboxes, the beauty of cotton fields dotted with sharecropper shacks, and the stillness of laundry drying on a rickety porch.

Ken Light, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism, calls the work an important body of visual documentary. “We often see the Selma march, the speeches,” Light explains, “but we forget the day-to-day struggle of people in the smallest communities, fighting for their rights.”

Now, 50 years after the summer of 1964, Herron has curated the group’s photos, added narration, and published an elegant book, Mississippi Eyes. (The photos shown here were taken by Herron from 1963 through 1965, and some appear in another book, This Light of Ours.) Mississippi Eyes, says Light, “is not an art book. It’s a thoughtful telling of a mostly unseen story.”

Herron first met Lange a few years before he headed South. “Dorothea was kind to me,” Herron writes in Mississippi Eyes. “She spent some minutes looking at my rather undistinguished pictures, and more time talking about what it meant to devote oneself to photography as a life calling rather than simply a profession. She told me that living visually was a lot like taking up monastic orders.”

Today, as Herron sits in an antique chair in his dining room in San Rafael, Calif., his voice becomes tentative, his words attenuated, as he remembers that meeting. “We talked maybe for half an hour,” he says, staring out the window at a mass of cymbidium orchids. “You know how this works: You have a moment with somebody. The connection is fleeting, but they say things to you that change your direction.”

He struggles to contain a current of emotion. “After being with her, I just said, ‘This is what I want to do with my life.’”

Herron hadn’t entered Princeton intending to be a photographer. He was toying with the idea of a career in the State Department. But he was moved by sculpture classes taught by former boxer Joe Brown, and recalls a seminal moment when he was writing an art-history paper on Georges Henri Rouault. He remembers spending an inordinate amount of time looking at the French Fauvist’s “The Old King.” “Suddenly it spoke to me,” he says. “I began to see why the painter had used the technique he had.”

At the same time, Herron was influenced by the World War II veterans who had founded his eating club, Prospect. He joined ROTC to avoid the Korean War draft, but found his antiwar views growing stronger. He resigned and applied for status as a conscientious objector.

After graduation, still thinking of a career in the Foreign Service, he began a master’s program in Middle Eastern studies at the University of Michigan. He found the course boring, except for the art. He had more fun taking ceramics. When his CO status came through, he took a teaching job at a Quaker school in Ramallah, a small town in the West Bank then under Jordanian rule. He failed in his attempt to locate a ceramics studio where he could continue making art, but, he says, cameras were cheap. “I bought an Exakta in Jerusalem and started shooting. I built a darkroom at the school and taught the kids. When photojournalists came through looking for guys to schlep cameras, I was nominated.”

Students from Whittier College visited the school, and one day he followed a group of them, led by student Jeannine Hull, as they cleared rocks from a field. “Why don’t you put down your camera and start to work?” he remembers her saying to him.

The two were married in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1956.

A year later, the Herrons moved home, to Rochester, N.Y. Matt started to work for Eastman Kodak and became a student of the photographer Minor White. Jeannine, the daughter of a Quaker who had been a conscientious objector in World War I, joined Women Strike for Peace. At a certain point, she remembers, they realized that if they wanted to see what nonviolence was about, they had to go to the South.

After that Sunday in Birmingham in 1963, they settled in Jackson, Miss. Matt Herron began shooting photos for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and taking magazine assignments that came his way. By the next summer, in 1964, Jeannine and the children had moved to Atlanta, where she worked with SNCC. Matt settled in Mileston, a hamlet in the Mississippi Delta, and lived his dream of doing the kind of work practiced by Lange and others during the Depression.

Documenting this history “was not easy for these photographers,” says Clay Carson, a historian and the director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford. “It was not a good career move. This was entering what was a war zone. Segregationists were intent that no one outside saw what was going on in the South.”

Dave Prince, one of the photographers, suffered a savage beating while shooting a meeting at a black church. Cars were torched. Herron was chased though a field, his cameras swinging, by a deputy sheriff wielding a billy club.

“I would strap on my cameras like armor plate,” Herron recalls. “They gave me courage that otherwise I lacked.”

He kept taking photographs after the summer ended, but by the early ’70s, Herron found that his magazine clients were gone or in their last throes. He changed course. With his wife and two children, he wrote a book about the family’s two-year sailing trip to Africa. He took part in the first Greenpeace whaling voyages and wrote about his experiences for Smithsonian. Then he got involved in labor organizing, eventually becoming chairman of the American Society of Media Photographers’ International Committee.

In the mid-’80s, he started a welding company to build structured steel frames for houses. He went back to skiing at 50 (having started a ski team at Princeton). When he turned 70, he learned to fly, got certified, and bought a glider.

“The last time I filled out a W-2 form was in 1958,” Herron says, leaning back in his chair. These days, he runs a stock-photo agency out of his home.

He is wearing jeans, a cable-knit sweater, and sandals. His mostly white hair is pulled back into a ponytail. It takes conviction and resilience to lead the unconventional life; he says he relies on his Quakerism, his Zen Buddhism, and his genes.

“My mother died at 107. She was a weaver, a tapestry designer, a knitter, a spinner, she dyed fabrics; she was the first weaving teacher in Rochester. When she began to lose the ability to do certain things, she took up other things,” Herron says.

“I get caught by enthusiasms and I follow them,” he says. “My latest is studying the double bass. I play with a small orchestra at the College of Marin. Tonight I’m going to visit a new orchestra to see whether I might join. It’s way above my head, but I like things that are above my head.”

Of his most recent endeavor, Mississippi Eyes, he says, “This piece of history was going to be lost if I didn’t tell it. It was an intense couple of years. I’ve never lived since in a truly integrated, beloved community. I regret that deeply. But you keep moving on.”

Constance Hale ’79 is a San Francisco-based journalist and the author of Wired Style, Sin and Syntax, and Vex, Hex, Smash, Smooch.

Herron: I spent five days walking backwards, looking through my lens with a pack on my back. I have no idea where I slept, or what I ate, or anything. I’m sure I probably had a bedroll and slept on the ground. People were pretty frazzled out by the end of the day’s walk.

I really wanted to isolate the figures against the sky. I had to find a ditch. So I spent a portion of that day throwing myself into ditches and shooting up from there. In this picture, you know, the forces of creation smiled on me: Every arm, and every head, and every leg is in perfect juxtaposition.

The American flag is really a beautiful device. And flags, of course, were highly symbolic in those days. If you carried an American flag, your message was, “I would like the laws of the United States to be enforced in the South.” If you had a Confederate flag on the back window of your pickup truck, you were saying, “Segregation forever.” People were pulled from their cars and beaten on the highways of Mississippi because they had an American flag decal on their license plate.

Herron: I was walking down the street and saw a “Lawn of the Month” sign and a black gardener. It summed up the entire economy of the Deep South, from the neocolonial pillars on the house to the approval of the Jackson Garden Club. And here was the guy who was really responsible, weeding.

Herron: I arrived at the church, and it didn’t look that bad. It was a brick building, and they had covered a hole with canvas. There were some broken windows. I took pictures of it, but they didn’t convey the violence of the act. And then I saw this car nearby, which had suffered the effects of the blast and had a blown-out front windshield. I crawled into the front seat and shot the church through the window of the car.

A good photojournalist is always looking for a way to intensify the image. Today, people will have this whole pasture here and somebody doing something over there. Those pictures never ran in the ’60s. We were always looking for ways to increase the drama, magnify, make pictures that were strong enough to make it into the magazine.

This was a single frame. Compositionally, there had to be the church in the picture, and there had to be enough of the window to say “violence.”

Herron: This is Fred Shuttlesworth’s church, Bethel Baptist Church. Martin Luther King Jr. was giving a speech to a packed church, and they were reacting. People were going crazy because he was the lord, he was their leader. King had been there before, doing demonstrations, and had gone to jail in Birmingham. He’d come back at a moment of pain and tragedy and confrontation. So they were celebrating the fact that he was there. I saw those hands go up. That’s a straight-on shot.

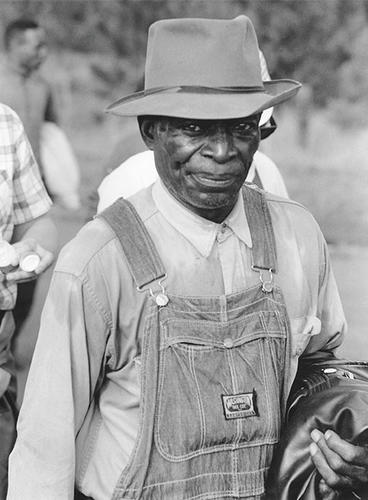

Herron: This is from the Selma march, in Lowndes County, in the heart of Alabama. At the time it was 60 or 70 percent black. There were no registered black voters. It was the epicenter of segregation. This guy probably came out of the fields and joined the march. I don’t know how he knew about it. There was a great grapevine system going on in Lowndes County.

A lot of people were shooting pictures of Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Bunche, Rabbi [Abraham] Joshua Heschel. Harry Belafonte came in later. Sammy Davis Jr. came down in his jet for the final day. That wasn’t the march, as far I was concerned. I felt that this was a march of ordinary people.

I just love his face. And the fact that he is wearing his work clothes. The sweat on his shoulder. He was proud to be photographed. He wasn’t a bit afraid.

Herron: This is currently my favorite picture. This was in the summer of ’64, at a church service of a small church of sharecroppers, black sharecroppers. These people were the poorest of the poor. And Sunday was the big day for them, for a number of reasons. First of all, on Sunday they called each other “Mrs. Smith” and “Mr. Brown.” It was not “Maisy” and “Robert.” That’s what their white overseers called them. This was the time when they could give and receive respect and could repair the damages of the week before and be who they were, be proud of themselves. It was important to look your best.

So after church, there are these guys in the back, you know, young men. And I just said to them: Why don’t you stand there and let me take your picture? They arranged themselves, so there’s a whole sociology here. There’s a kid who feels left out, and you know, he’s not dressed very well. The older ones are all in the back because they don’t quite trust me. These three [front] are dressed in their best clothes — those two, really — they’re standing so proud. You know, “Look at me.”

I revisited that church 20 years later. They had an undistinguished cinder-block structure in place of the original clapboard church, which was quite beautiful, but which must have appeared to them to be old, and ramshackle, and run-down. I spent the evening with the pastor in his kitchen, sitting around the table. One of the things he said to me was, “You know, people used to walk the dusty roads to church carrying their shoes so they would be spotless for the service.”

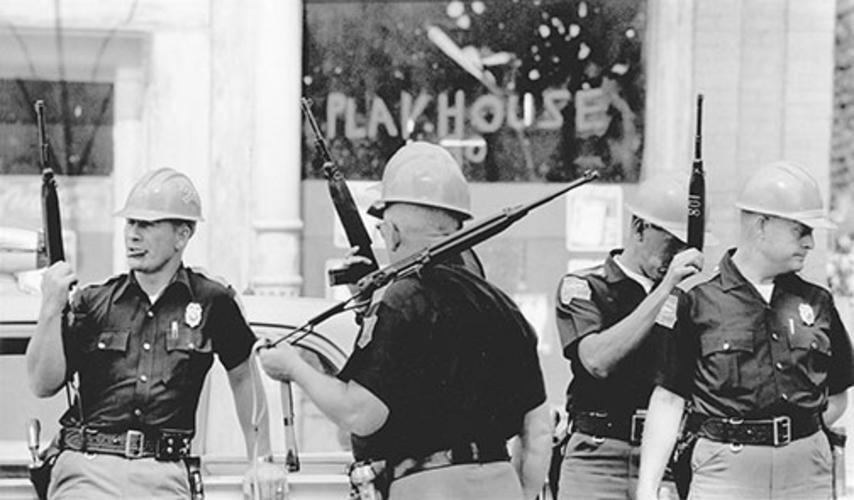

Herron: This is during the riots that developed in response to the church bombing. Birmingham was an extremely tense place at the time. These are four of the 300 Alabama state troopers that the commissioner of public safety, Al Lingo, brought to patrol Birmingham. The troopers had a nasty reputation for violence against blacks — something I witnessed one night when they shot buckshot into the back of a young kid after yelling a profanity at him. They patrolled five to a car, with guns protruding from the windows.

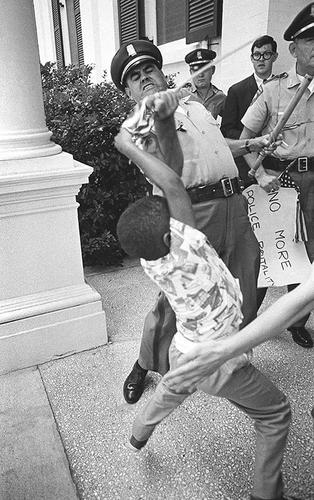

Editor’s note: This is from a series of four photographs of Anthony Quin, who was attending a voting-rights protest with his mother at the governor’s mansion. It won the World Press Photo Contest in 1965.

Herron: This was in the summer of ’65. The civil-rights groups in Jackson were trying to break the back of segregation there, so their intention was to fill the jails. After they filled the jails, the police opened up the fairgrounds, and they started incarcerating people in cattle pens in the blazing sun.

Aylene Quin had a beauty parlor in McComb, Miss. McComb was hard Klan territory. Mrs. Quin was a mother who became active in civil rights when most people were terribly frightened to do that. About a month before this picture was taken, the Klan threw a firebomb through her front porch. Anthony Quin was sleeping in the front room, and the ceiling came down on top of him. So, at 5, this kid is a civil-rights veteran.

Anthony has got this flag, the American flag, a symbol. The highway patrol shows up and starts leading people away. Mrs. Quin says to her son, “Anthony, don’t let that man take your flag.” So Anthony holds onto the flag. The patrolman, Huey Krohn, probably had never met resistance from a small black child before, and he’s trying to take the flag, Anthony’s hanging onto it, and Krohn goes temporarily berserk. So Krohn wrenches the flag out of Anthony’s hands. And the gods of chance sent me this sign in the background being held by another policeman: “No more police brutality.”

3 Responses

Ted Miller ’55

10 Years AgoHelp in the Darkroom

Thank you for the article about Matt Herron ’53 (cover story, June 4). I hope that Matt will remember me and, apropos of the article, the help that he gave me to nurture my own interest in photography.

During our years at Princeton there was a darkroom in the basement of Holder Hall, where he taught me how to develop black-and-white film and make black-and-white prints. I continued shooting black-and-white film and making black-and-white prints in the 1960s and have never lost interest in the subject. I did not know about his work in the civil-rights movement, for which I admire him greatly. I enjoyed the photos and text of the PAW article.

Scott W. Reed ’50

10 Years AgoCivil-Rights Images

Thank you so much for “Being There” (cover story, June 4) on Matt Herron ’53’s photographs about civil rights in Mississippi in 1964. The pictures and the story indicate great courage on his behalf, not only for himself but to organize a group to photograph all of the terrible things that were happening in the South.

I thought the nine pages plus the cover were simply outstanding, and also horrifying reminders of what a terrible time it was for blacks in the Deep South.

Marjorie White s’64 p’92 p’93 p’94

10 Years AgoCivil-Rights Images

Please convey to Matt Herron that his 1963 photograph, “Ladies in Church, Birmingham, 1963,” was not made in the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth’s church, Bethel Baptist Church, now a National Historic Landmark.

Bethel, headquarters for the Birmingham movement under the leadership of Fred Shuttlesworth, was bombed in 1956, 1958, and 1962. Its figurative glass windows were long gone when Herron arrived in 1963 in Birmingham to photograph the aftermath of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing of Sept. 15, 1963.

Editor’s note: Matt Herron replied that a New York Times article on Sept. 16, 1963, reported a bomb threat at the New Pilgrim Baptist Church, where the Rev. Martin Luther King and other movement leaders were conducting a meeting. “That’s probably as close as we can get to a positive church identification,” Herron said.