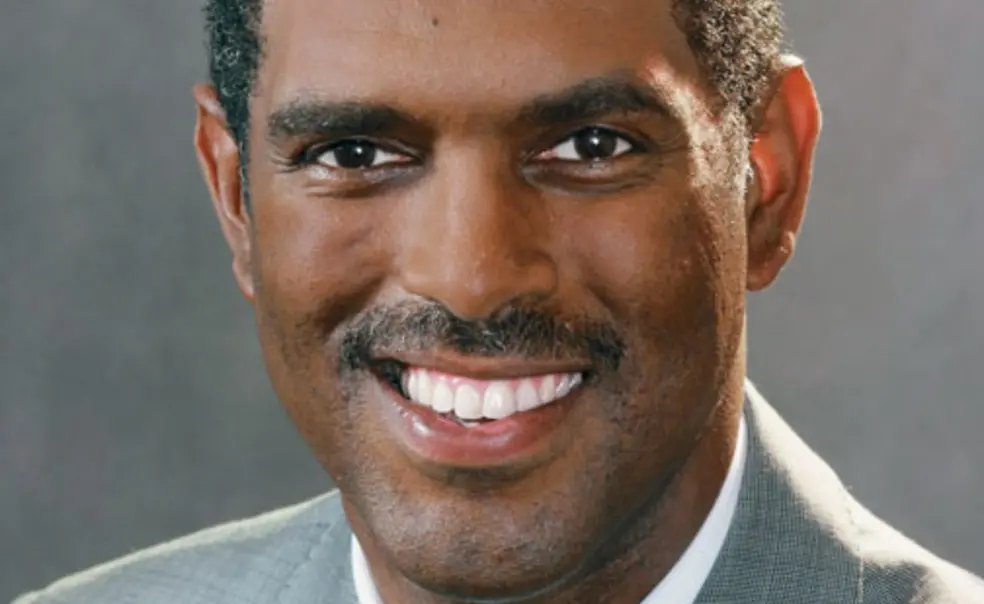

A moment with ... Steve Mills '81

Steve Mills ’81 never played in the NBA, but the starting guard on two Ivy championship teams has had a long career as a basketball and entertainment executive. Mills worked for Chemical Bank before landing a bottom-rung job in the NBA front office, eventually rising to become the highest-ranking African-American in the league. He played a leading role in the creation of the WNBA before leaving to become vice president of the New York Knicks and, from 2001 to 2009, president and chief operating officer of MSG Sports, the entity responsible for three professional teams and all other sports-related activities at Madison Square Garden. Now working with Magic Johnson Enterprises, Mills also is co-teaching a freshman seminar on “Dilemmas in Intercollegiate and Professional Athletics.”

How has the sluggish economy affected athletics?

The major sports will ride this out, but I do think that, in the 26 years that I have been involved in professional sports, this is the first time I have seen owners make decisions about player compensation that are a function of outside economic issues. Many owners no longer have the ability to fund player expenses on an unlimited basis. At the college level, there is pressure on many athletic departments to shave budgets on non-revenue-generating sports and try to maintain those programs that can raise revenue.

The NFL is nearing the end of its labor agreement. There is talk of a lockout in 2011. Why can’t players and owners get along?

I’ve participated in the negotiations of three collective-bargaining agreements with the NBA and one with the WNBA, and the vast majority of the time you find a way to make a deal. But the current economy has changed things. When there is less demand for some of the premium products a team sells, such as luxury suites, that changes the financial outlook of teams in a significant way. It has been rare to open a new stadium and not have all the premium seats sold ahead of time, but the two New York football teams, the Giants and the Jets, are opening a stadium next year and they have been having that problem.

Some people complain that there are too many teams and too many games. Are professional sports spread too thin?

I don’t necessarily agree that there are too many games. In a perfect world, maybe you would shrink the playoffs. In a few of the sports, maybe expansion was pursued too aggressively, and if you were starting over you’d have some contraction. But once you have 30 teams, it is very difficult to move down to 26 teams, even if 26 is the right number.

What is it like working in the New York sports market?

There is an incredible amount of pressure that comes from a number of different angles. The fans are knowledgeable and have a sense of ownership in their teams, which you love. There are also financial expectations on the corporate side, and sometimes they conflict with the resources that you need to try to win. Then you throw on top of that the most intense media environment anywhere in the United States. Managing through all those issues is what makes working in New York difficult, but it’s also what makes it great.

Is it a problem when college coaches are getting paid more than the college president?

When I wear my professional hat, I think that is the way of the world. The dollars flow to where the demand for the people is the greatest. So if you take a great college coach, if he didn’t make X in the Southeastern Conference, he would make X in the NFL. In order to keep the great coaches in college, if that’s what the market demands, you pay what you have to pay until the market changes. I would assume that a college that pays its football coach $5 million a year believes that he is delivering more than $5 million worth of value to funding its athletic program.

Is the Ivy League model of athletics still viable today?

I think the Ivy League model is very good. I believe it strikes the right balance between athletics and academics. To go to a place like Princeton, where you can compete against Division I schools but also be in an environment where academics are really important — there is no substitute for that. In the Ivy League, you’re not there just to be a basketball player. You are a student and a basketball player.

Some have complained that even in the Ivy League, athletes are not well integrated into the broader life of the university. What was your experience?

We didn’t live in athletic dorms. You were with your teammates for the three hours a day that you were practicing, but I ate and lived with the students at Princeton Inn, I was part of the Third World Center, so I felt fully integrated into the life of the University. Now I have great relationships with my old teammates, but I also have them with classmates who didn’t participate in athletics.

— Interview conducted and condensed by Mark F. Bernstein ’83

No responses yet