'Old North' In Pictures

Early photographers captured Nassau Hall, along with now-gone campus landmarks

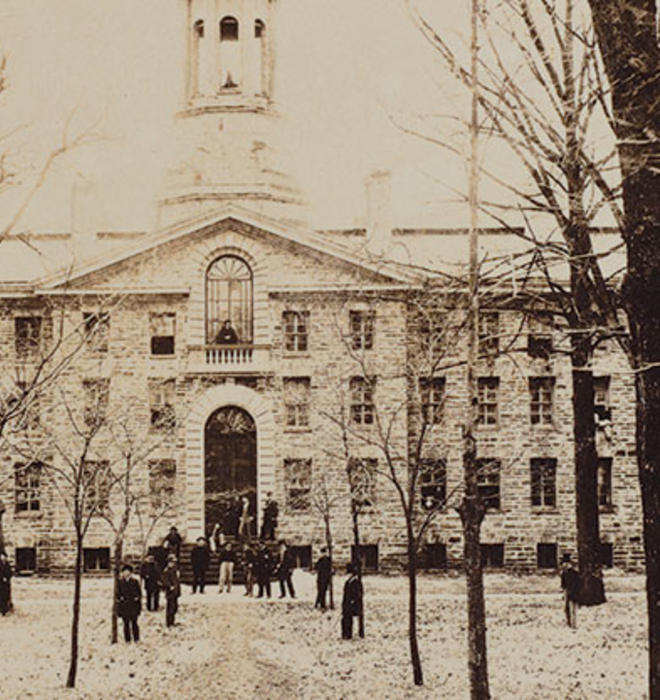

New York photographer George W. Hope, summoned to photograph the senior class at Christmastime, climbed a ladder to get this unusual, high view of Front Campus. The keystoned arches and balustrade had been added in the recent restoration. Days earlier, the 13th Amendment had abolished slavery; decimated by the defection of all the Southern students during the Civil War, Princeton’s enrollment remained small.

Few buildings have flirted with the camera as long as Nassau Hall. Its photographic record dates to 1860, a treasure trove for the historian. Some of the earliest pictures never have been reproduced, until now.

On a windswept night 160 years ago this month, Nassau Hall went up in flames — for the second time. Only looming stone walls survived from the Colonial structure of 1756. Nassau Hall’s three-year restoration by Philadelphia architect John Notman gave us the edifice we admire today, with its tall Italianate cupola. It is this building that early photographers captured.

Invented in Paris in 1839, photography reached New York and Philadelphia almost immediately, and daguerreotype artists were busy taking portraits of graduating Princeton students as early as 1843. But we have no outdoor photograph of campus before about 1860. For the historian, the Holy Grail would be a photograph of Nassau Hall showing the stubby, pre-fire cupola. Perhaps one languishes in a drawer someplace. Philadelphia photographer Frederick DeBourg Richards took a salt print of Princeton Cemetery in September 1854: If only he had visited Nassau Hall the same day, we could see the true antebellum appearance of the building.

Like the famous images of Civil War battlefields, the first photos of Old North are albumen prints, oversized paper positives made with egg whites and mounted on cardboard — the image generated from glass wet-plate negatives. The large prints are time-travel machines packed with myriad details of the Victorian campus, from buildings under construction and repair, to new plantings and pathways, to pumps used for drinking and innovative gas lighting fixtures.

The early photographers were professionals brought here from New York City, Philadelphia, and even Montreal to take pictures of the senior classes. Sentimental graduates liked to stuff albums with autographs and pictures of the campus, knowing that they might never see the place again.

In fact, Princeton invented that modern staple, the photographic yearbook, which debuted here with the work of Massachusetts photographer George K. Warren in 1860. Happily, different classes hired different photographers, giving us a rich variety of views, an astonishingly complete visual record housed in Mudd Library and recently made available online (http://pudl.princeton.edu/collections/pudl0038).

No album was complete, of course, without a photograph of Nassau Hall. For many students, it was home: Old North then served as a dormitory, in addition to housing the library. And everyone cherished it as the original edifice of the College of New Jersey, scarred by the Battle of Princeton and briefly Capitol of the United States in 1783. Through the magic of photography, the 19th-century graduate could always enjoy the thrill of “going back to Nassau Hall.”

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 has been studying old campus photographs since his senior year, many of which appear in his book Princeton: America’s Campus.

Young New York photographer William Roe Howell took some of the best early pictures of Princeton. Here the tower of Old North rises above the rooftops of Nassau Street stores and the Colonial Nassau Inn. The Princeton Nine plays the formidable Athletics of Philadelphia in a ballfield at the foot of Chambers Street. Princeton was said to be the most illustrious 19th-century college to occupy so small a town.

When Seventy-Nine graduated, it donated two zinc lions ordered from J.L. Mott Iron Works in New York — the first gift of a class that would produce a U.S. president and become legendary for devotion to alma mater. Lions were the emblem of the House of Nassau. Within a decade the tiger had become Princeton’s mascot, and in 1911 bronze tigers chased away these lions, which today are found at Wilson College. The custom of planting ivy began on Class Day 1877, and vines would engulf this bare façade by century’s end.

Could this be our earliest campus photograph? Looking eastward from the rural vicinity of the Princeton Theological Seminary, the proud cupola of reconstructed Nassau Hall rises above the rooftops of the big stone dormitories of the 1830s, East and West Colleges. Prominent, at left, is the barnlike gymnasium of 1859 (it burned down in 1865), which stood about where Blair Hall is now. Behind it appears the Joseph Henry House, still with white paint on its side porch; it was painted darker sometime during the Civil War.

Students hang out the dormitory windows in the earliest detailed photograph of Nassau Hall. Philadelphia photographer John Moran had an adventurous career as a photographer of the Civil War and later on far-flung expeditions. The mortar still looks white from the post-fire renovation of less than a decade earlier. Devoid of plantings, the place appears as stern as it must have when George Washington knew it.

Walkways were still unpaved when George K. Warren set up his tripod during the era of President Ulysses S. Grant, who visited a year later. Nassau Hall stands at far right. The camera shows the scene just after the 1870 completion of Dickinson Hall (left rear) but before the 1871 demolition of Philosophical Hall (center). The twin of Stanhope Hall, which it faced, Philosophical had been built 65 years earlier as a science laboratory, but it was about to be replaced by Chancellor Green Library

Moran photographed the place we call Cannon Green, which had been thickly planted with trees in the antebellum period to discourage students from playing football. No matter: The lads devised a game that twisted in and among the tree trunks. Trees have been scorched by frequent bonfires around the cannon.

No responses yet