The Old West

Images from expeditions of another era — and what scientific explorers do today

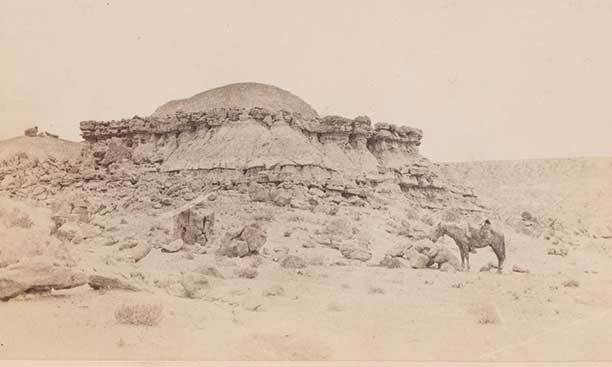

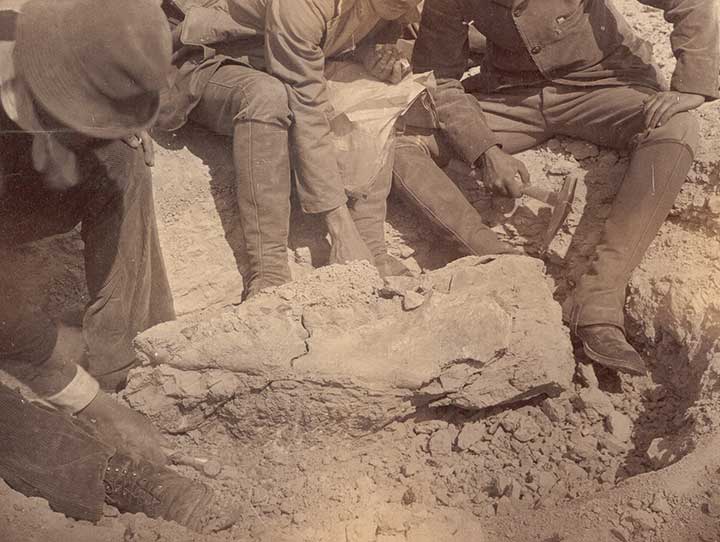

The railroad was still being laid across the West when students and faculty from the College of New Jersey went past the furthest tracks, scouring the Badlands in search of prehistoric beasts. Starting in 1877, parties from the College embarked each summer on scientific expeditions out West, largely to states that the Rocky Mountains cross, such as Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and the Dakotas. The expeditions sought fossil specimens to stock the College’s museum of natural history. Usually fossils lie in sedimentary deposits that haven’t been very compressed or contorted; the lands around the Rockies were ideal grounds for the fossil hunter in search of new discoveries. In the course of these journeys, the parties also found a world that was itself vanishing into the past: The Old West, a landscape of frontier towns, makeshift camps, and Native settlements, which photographs from the expeditions preserve.

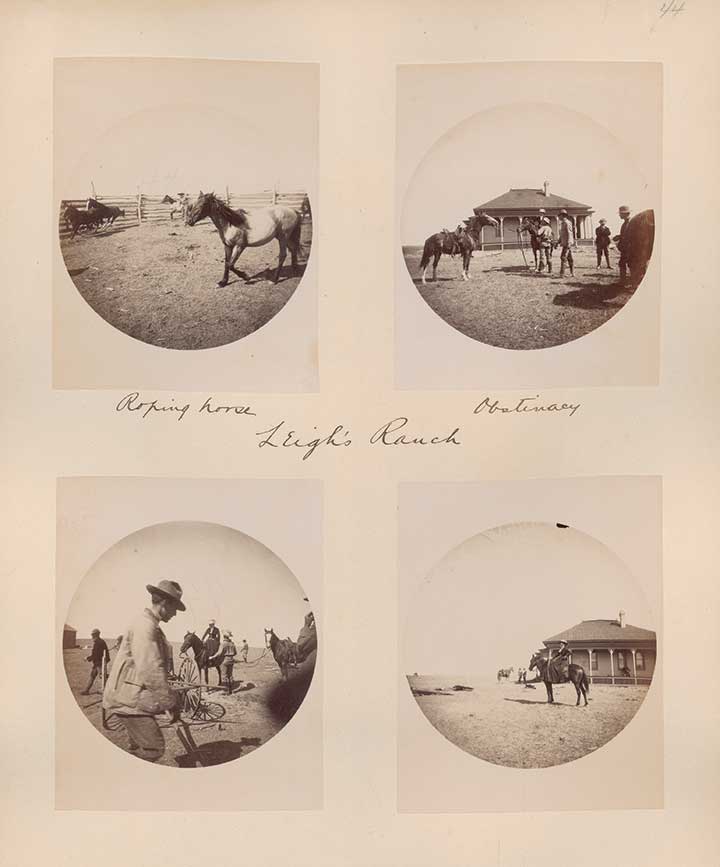

The expeditions required their participants to play a range of roles, from paleontologist to photographer to geological surveyor. Juniors and seniors could apply to join through a competitive examination; successful applicants, between eight and 13 each year, attended lectures before the trip on helpful subjects like osteology, the study of bones. In 1882, the students who had signed up to go west wrote up tongue-in-cheek rules for the expedition, the Princetonian reported. The rules included: Every member would grow a full beard — starting work on the growth “at once” — and carry his own tobacco; no member would keep rocks or fossils for himself; and no swearing would be permitted, unless it referred to the cooking, the insects, the instructors, the mules, or the weather.

An expedition party might travel more than 5,000 miles, some 1,200 on horseback. Depending on their plans and the terrain, party members might travel with saddle horses, packhorses, mules, or a four-horse wagon equipped with a teamster and a cook. In 1893, they hired a Deadwood stagecoach, an icon from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. In 1895, after a welcome respite on a train, they reached the end of the railroad tracks in Montana Territory — but managed to continue by rail to Wyoming by hitching a ride on a construction train, laying out their bedding on rumbling flat cars. They often relied on Indian agencies to find their way around; on a visit to one such agency in Wyoming, the travelers watched Native Americans play a game with some 60 players that resembled hockey or lacrosse. “After the game a Princeton cheer was given,” the Princetonian later reported, “which amused the Indians very much.”

They focused on collecting vertebrate fossils, but also took interest in gathering geological specimens and evidence of prehistoric plant life and river life. They found specimens of prehistoric camels, crocodiles, deer, dogs, elephants, fish, horses, lizards, mice, rhinoceroses, shellfish, turtles, and wolves, and much else besides.

The Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library holds hundreds of photographs from these journeys in its Princeton Scientific Expeditions Collection. The students, wise to new gadgets as in every generation, supplied from their ranks photographers who used glass-plate cameras and tents set up as darkrooms to record the adventures of Princetonians out West.

Today, research expeditions remain part of the bedrock of the Department of Geosciences. Two or three undergraduate classes set out each year on expeditions during school breaks — to the Everglades, the Bahamas, the Republic of Cyprus, or farther still. Faculty members conduct research expeditions all over the globe, sometimes taking their lab groups with them. Scientists often pitch camp for weeks at a time, working in the wilderness as their predecessors did. In many places, they still use local agents as guides and suppliers (for instance, if a scientist needs to get hold of liquid nitrogen while in another country). They may work, with permits, on indigenous lands. And those scientists who join research programs in Antarctica or expeditions at sea on research vessels can justly claim to be voyaging in strange and lonely regions.

Adventurers from Guyot Hall no longer seek large prehistoric animals, but rather incredibly small ones. “We haven’t gone out to do big-animal paleo in at least the past 20 years,” says Bess Ward, the chair of the Department of Geosciences. “We look for little tiny things that you might never have heard of, or for chemical signatures that are left behind in rocks.” Scientists examine rocks for foraminifera, or microscopic animals with intricate shells of calcium carbonate. They use mass spectrometry to study the isotopes in water and carbonate rocks. The questions asked, conversely, are much larger: What caused the event that wiped out the dinosaurs — a meteorite or a huge volcanic eruption? How much has the sea level changed over the millennia? What is the role of the ocean, which holds most of the carbon dioxide we produce, in moderating global warming?

“Compared to traditional paleontological expeditions, we have a more global view,” Ward says. “We visit a place not just because it’s interesting in itself, but because it can tell us more about the larger world.”

As much as the frontiers of our knowledge have changed, the world of past generations lingers in the fossil strata of the University. The department still has endowed funds — from the old days — set aside for packhorses. “When I first became department chair, I looked through the records to find out what funds we had available and what their requirements were,” Ward says. “One phrase stood out to me: ‘The department may use this fund for packhorses, but not office furniture.’”

Elyse Graham ’07 is an assistant professor of digital humanities at Stony Brook University.

No responses yet