Sometimes an event is more significant for what does not happen than for what does. A case in point might be a talk last December by school-shooting survivor Kyle Kashuv.

The 17-year-old Kashuv was invited to campus by the Princeton chapter of Turning Point USA, a national group that promotes grassroots conservative activism. A student at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., at the time of the February 2018 mass shooting, Kashuv had received national attention for speaking out against gun-control efforts promoted by his classmates and for opposing the student-organized March for Our Lives. (As this article was going to press, Kashuv was in the spotlight again, for racially offensive remarks he made in private two years earlier.)

According to an account in The Daily Princetonian, Kashuv’s talk in McCormick Hall was attended by about 75 people. The audience listened attentively and peppered Kashuv with questions afterward. “It’s still kind of crazy to me why a bunch of Ivy League students would care what a 17-year-old schmuck has to say, but I’m very grateful that you guys came here tonight,” Kashuv said. Whether anyone’s mind was changed is unknown, but in a way, that’s beside the point.

Riley Heath ’20, the president of Princeton’s Turning Point chapter, says that shortly before the talk, someone kicked over the group’s table outside the lecture hall and ran off. Several students later complained that the group’s email invitation, which was sent to all undergraduate addresses, had misrepresented Kashuv’s views.

But no one tried to block Kashuv from speaking; no one shouted him down. Listening respectfully to opposing viewpoints is the sort of conduct one might expect — ought to expect — at a university, but that has not always been the case. There have been many well-publicized incidents around the country of unpopular speakers, often conservatives, being blocked from appearing on college campuses.

Conservative students at Princeton know they are outnumbered and feel that their views are derided or ignored, but for the most part, they say, they are left alone. In Heath’s opinion, self-censorship is a greater campus problem than anti-conservative animus. Students of all political stripes are loath to offend anyone, and some of them suggest that conservatives in particular are cowed into silence on controversial topics, particularly concerning race and sexuality, lest they be branded as hateful on social media.

“Most people at Princeton, they don’t really care about the whole left/right, Republican/Democrat divide,” Heath suggests. “They care more about issues. But they also care about their careers. Getting politically active is not something that really they want to do.”

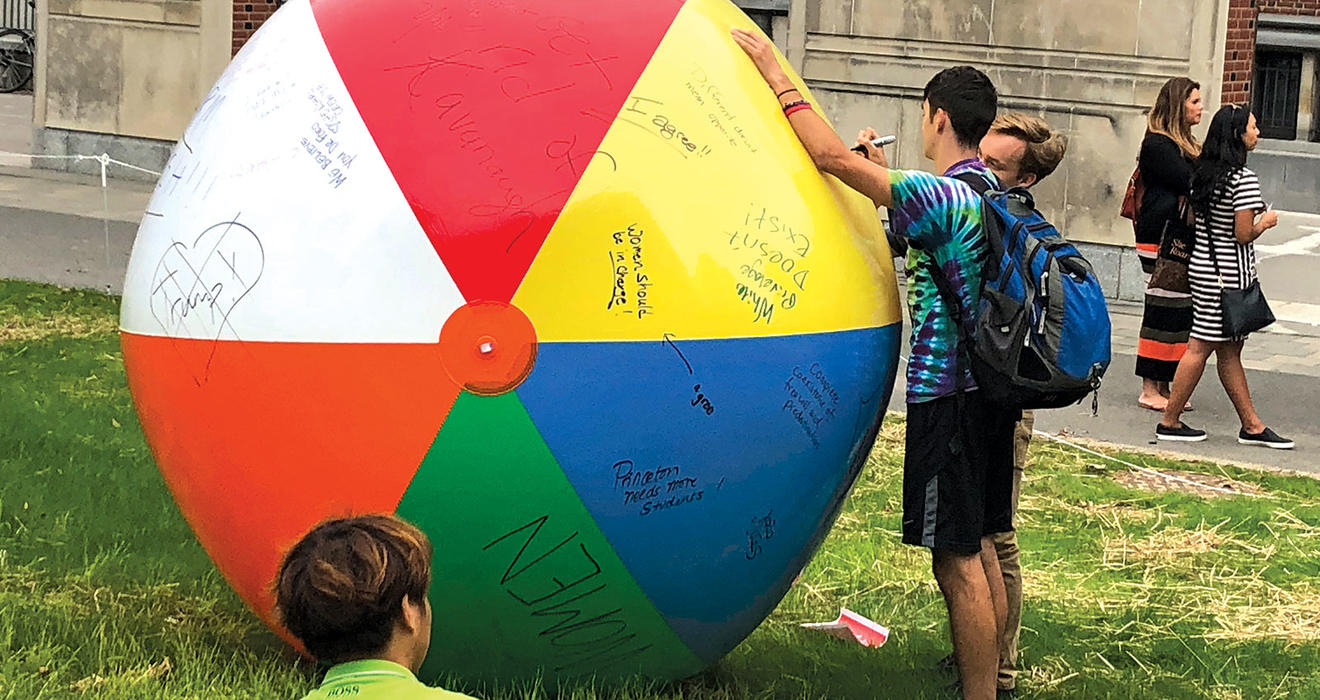

And so last fall, to generate attention for Turning Point, Heath rolled out a huge beach ball, dubbed a “free speech ball,” and invited passersby outside Frist Campus Center to decorate it with their most unpopular opinion. Contributions ranged from “Hillary is a demon” to “Believe women.” One student, who could not be plotted on the political spectrum, scribbled: “Princeton is a little overrated.”

The political chasm that divides the country is not completely absent from Princeton. In the last two years, Whig-Clio disinvited University of Pennsylvania law professor Amy Wax, controversial for her views on race and culture, while the Center for Jewish Life canceled a presentation by Israel’s deputy foreign minister after students protested the invitation (another group ended up hosting the speaker, and the CJL apologized).

In response to these incidents, the University created a team of “open-expression monitors” designed to protect the rights of both speakers and protesters at campus events. (Some students protesting Princeton’s Title IX policies have said the monitors restrict speech.) Rochelle Calhoun, vice president for campus life, said at a CPUC meeting in September that University groups should not rescind an offer to an invited speaker: “It is not good for the inviting group, it’s not good for the University, and often it gets used in ways that we don’t want to elevate the individual’s public statements.”

Princeton’s students and faculty probably have leaned to the left since at least the Vietnam War. That is true at most American colleges. Does it matter? A Gallup poll taken in March 2018 found that 61 percent of U.S. college students believed the climate on their campus prevented people from speaking their minds freely, up from 54 percent the year before. Fully 92 percent believed that liberal students could express themselves without fear of reprisal, but only 69 percent believed conservatives could.

While it is unknown how Princeton students answered the poll, by and large, conservative students at the University tell PAW they are able to speak their minds freely, both in class and out of it. They are not harassed or shunned socially. The silence that greets them when they express their beliefs may be deafening, but for the most part they do not perceive that it is hostile.

“Princeton is actually great on that front,” Akhil Rajasekar ’21 says of the treatment he has received from his more liberal classmates. “When you see some of the stuff that is happening at Berkeley and Yale ... .”

“Politically it’s pretty dismal,” adds Will Crawford ’20, president of the College Republicans. “But this might be the best place in the country to be a conservative student, because the administration and professors are committed to making sure that people don’t get railroaded out of a conversation.”

Kashuv’s speech was not the first such non-incident. When conservative author Charles Murray appeared at Middlebury College in March 2017, more than 100 students refused to let him speak, shouting over his lecture, pulling fire alarms, and shoving Murray and a faculty member. When Murray had spoken at Princeton three months earlier, the reception was different. Just before his lecture began, anthropology professor Carolyn Rouse and several dozen students walked out in silence. Murray then delivered his remarks uninterrupted.

Whether these examples of tolerance are achievements to be celebrated or a graveyard to be whistled past remains to be seen. Conservative students, however, credit the University administration and prominent conservative faculty members for fostering a culture that expects people to respect opposing points of view. They especially single out the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions for inviting conservative speakers to Princeton and providing a place where conservative points of view can be heard.

“We’re blessed by having an administration that is strongly committed to freedom of speech, and not as just an abstract right but as something that is central to the University’s mission,” said Professor Robert George, who heads the Madison Program and is Princeton’s best-known conservative faculty member. “The pursuit of knowledge requires that there be openness to hearing other points of view.”

Princeton boasts a long list of prominent conservative alumni and several active conservative student groups, many of long standing. These include the Cliosophic Society, College Republicans, the Princeton Tory, Princeton Libertarians, Princeton Pro-Life, and the Anscombe Society, which says it is “dedicated to affirming the importance of the family, marriage, and a proper understanding for the role of sex and sexuality.” Since the 2016 election, Princeton has added chapters of Turning Point USA, the Federalist Society, and the Network of Empowered Women. Conservative alumni groups also have been active in the past, most prominently Concerned Alumni of Princeton, founded in 1972 largely in opposition to University policies on coeducation, affirmative action, and ROTC. The group disbanded in 1986 but still came up in the Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Samuel Alito ’72, who had been a member.

In recent years, the University has made particular efforts to promote civility and protect debate for all points of view. In 2015, the faculty adopted a statement expressing its commitment to free speech and asserting that Princeton guarantees “the broadest possible latitude to speak, write, listen, challenge, and learn,” including the expression of ideas that may be “unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive.”

In 2018, President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 endorsed a statement by the Association of American Universities promoting free speech. “Robust debate and vigorous argument are essential to the research and teaching missions of America’s leading universities,” he said, calling free expression “a value that is critical for the future of higher education in our country and for democracy more broadly.” To further spread that view, Eisgruber chose politics professor Keith Whittington’s book Speak Freely: Why Universities Must Defend Free Speech as the University’s Pre-read last summer.

These efforts seem to have paid off.

Nicholas Sileo ’20, a staff writer for the Tory, may be a staunch conservative, but he is satisfied with the campus climate. “You hear horrible stories of things happening around the country at our peer institutions, of people being shouted down, unable to voice their opinions.” At Princeton, he says, “you get a few icy looks, which I think is a shame. But if that is all we have to face, it really isn’t too much of a problem.”

Asked if a conservative student could walk around campus wearing a Make America Great Again hat, College Republicans president Crawford looks perplexed. “I think that would be a silly thing to do because people will think you are a kook,” he finally replies. “A lot of people would not like it and think it was a weird thing to do, but I don’t think they’d throw their coffee on you.”

Still, conservative students agree, respect is a two-way street. While many college conservative groups have hosted button-pushers such as Milo Yiannopoulos, Rajasekar says that he would not invite the former Breitbart News editor to Princeton because Yiannopoulos seeks to agitate rather than enlighten.

“I don’t care if a speaker is controversial if they have something substantive to say,” Rajasekar reasons. “Attend the event and figure it out [for yourself]. But I don’t want to bring in someone whose whole purpose is to be provocative. ‘Owning the libs’ is not at the top of my priorities.”

Academically, conservative students say they face a universe in which progressive views on everything from climate change to immigration to race relations and gay rights are taken as a given. Claire McCarriher ’21, president of the Network of Empowered Women and member of both the Cliosophic and Anscombe societies, says she doesn’t hesitate to question orthodoxies in class or precepts. Rajasekar suggests that being in hostile academic territory forces conservatives to hone their analytical and rhetorical skills. “When professors have overwhelmingly liberal biases, it’s great for conservatives,” he believes. “Because the whole time your mind is churning: ‘I don’t agree with that, what is the best argument I can muster?’ And that’s great for me. But I think it is bad for liberals, because you are never really exposed to the other side if no one is actively presenting it to you.”

Protests against visiting conservatives, when they do occur, hardly evoke the Days of Rage. In April, when the James Madison Program announced the appointment of Marianna Orlandi as an associate research scholar, Yafah Edelman ’20 sent an email to the Mathey College listserv pointing out that Orlandi has worked for the Center for Family and Human Rights, which the Southern Poverty Law Center has classified as an anti-LGBT hate group. Edelman wanted to see Orlandi’s appointment rescinded, but told the Prince that the primary motivation was to provoke discussion.

Princeton’s conservative students embrace a broad range of political thought, from evangelicalism to libertarianism, but the conservative leaders who spoke with PAW overlapped in some areas — mainly, their dislike of the left and their embrace of the president.

Disgust with what he perceived as progressive groupthink drove Rajasekar from near-apathy all the way to the political right. In 2016, he voted for Hillary Clinton; less than a year later, he took an internship in the Trump White House. He explained his metamorphosis in a blistering op-ed for the Washington Examiner headlined, “The Repulsiveness of Ivy League Liberalism.” “Intellect and rationality were overcome by factionalism and emotion,” he wrote of progressive students. “It became clear that campus liberalism had few goals other than its own canonization as the sole intellectually acceptable view.”

In person, Rajasekar is less polemical than one might guess from reading his opinion piece. Asked his opinion of President Trump, he chooses his words carefully. “He says a lot of cringe-worthy things,” he answers, “but then he does a lot of things that I like, so the question is how to balance that.” He expects to vote for Trump in 2020.

Several other campus conservatives say they’re happy with the president, even if they were slow to warm to him. During the 2016 primaries, Crawford derided Trump as “some blowhard reality-TV-show person.” By November, he had overcome his objections, but he adds, “I don’t think that my voting for someone is a moral endorsement of everything they do.”

For Heath, Trump’s outrageousness is central to his appeal: He attended a Trump rally as a high school senior and found himself captivated by the candidate’s personality. “It’s kind of inspiring,” he recalls, “especially when I saw that so many people were afraid to talk about their opinions. He almost did it with his middle fingers up.”

Sileo was late getting on the Trump bandwagon though he, too, has come around. “Would he be my ideal president? Probably not,” he says. “But I like the fact that in some ways where we are getting so self-regulating, so insecure about what you can say and can’t say, that he is willing to shatter that wall and open up the dialogue.”

Ideally, college is a time for broadening one’s perspectives and trying on new ideas to see how they fit. Heath acknowledges that, as a vocal conservative, he may not be the most popular member of his class, but his time at Princeton has been all that he hoped it would be.

“I’ve definitely had a lot of conversations I wouldn’t have had, had I not set up a table or rolled around a giant beach ball,” he says. “I really like having conversations with people. Not all of them go well. ... For the most part it has been a pretty positive experience.”

In March, the Federalist Society invited Trump’s newly chosen Federal Communications Commission chair, Ajit Pai, to speak about net neutrality. Rajasekar, the chapter president, may reject the progressive orthodoxy he sees all around him, but he was pleased that the event in Lewis Library was well attended and that the audience listened attentively.

“Even if they didn’t agree, that’s not the goal,” he reasons. “They heard a view they hadn’t heard before. Maybe they’ll think, ‘I still believe what I believe, but that’s interesting.’ That’s all I’m working for.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

2 Responses

H. Grant Thomas Jr. ’67

6 Years AgoLessons Are In Order

I noted with interest “Orange and Black ... and Red” (feature, July 10) about the “free speech ball” that landed on campus, courtesy of the Princeton chapter of Turning Point USA, a national group that promotes grassroots conservative activism. And I noted with particular interest one of the inscriptions on the ball, which read thusly: “White privelage [sic] doesn’t exist.” Now, I don’t mean to butt in, but as a former English major, I’d like to encouridge the author(s) of this inscription to take advantidge of the University’s rumedial speling program. There’s so much to learn!

Norman Ravitch *62

6 Years AgoFree Speech and Academic Freedom

I am glad to hear that conservative students are not harassed or silenced at Princeton. I would, given my university teaching career in mind, worry more about the abuses of academic freedom by professors. I have encountered this very much in my career; I don't know the situation now, having been retired since 2001.