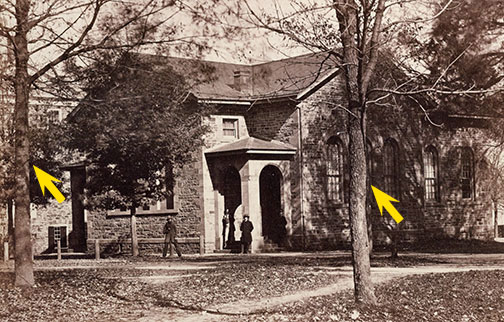

Among the trees that cast their shadows on the bus turnaround by East Pyne, the biggest is a tulip poplar. We hardly notice it as we hurry by, but this tree has witnessed much of the University’s history. Old photographs show that it was already tall when it stood in the side yard of a professor’s house in the 1870s; 50 years later, it miraculously survived the fire that destroyed nearby Marquand Chapel.

Not far away is the colossal tulip poplar, age unknown, on the Prospect House lawn: about 135 feet tall, the largest tree on campus. The Prospect grounds are filled with fascinating trees, including the huge ginkgo near McCosh Walk. Perhaps this specimen, native to Asia, was planted before the Civil War; or perhaps it was one of the 100 rare types President James McCosh ordered from the United States Botanic Garden in Washington in May 1879. No one knows.

Much of Princeton’s beauty is owed to the more than 400 species of trees that shade our paths, shelter Gothic buildings, spread gracefully above Commencements in front of Nassau Hall. Too often we take these trees for granted, and questions about who planted them, and when, are hard to answer — although faded old photographs give us clues.

University grounds have not always been filled with trees. At Oxford and Cambridge, quads are mostly grass. Even Princeton was virtually treeless until the Romantic Movement made nature a subject of universal fascination. Trees first were planted extensively here after 1800, transforming Front Campus from a barren field — strewn with cow pies — into a park of native elms, maples, and ashes. Antebellum Rear Campus, as the area behind Nassau Hall once was called, was planted with rows of trees, too — not just for beauty, but to stop undergraduates from playing football. Instead, the game evolved into what one student called “a bewildering calculation of intricate possibilities,” weaving among the tree trunks.

Lafayette Ash

Planted ca. 1825, girth 12’ 9”

Front Campus has been planted and replanted with trees since the Federal Period. Only this towering ash survives from the 1820s planting campaign that replaced imported Lombardy poplars with natives of the American forest — right around the time that the Marquis de Lafayette was feted in a “Temple of Science” erected in front of Nassau Hall.

All trees noted in this article will be labeled with explanatory text during Reunions.

Every subsequent generation has cherished campus trees, often taking extraordinary steps to protect them. It’s no easy task, given the vagaries of New Jersey weather and the onslaught of disease. Managing Princeton’s trees has been a ceaseless, two-century labor of love.

When Superstorm Sandy knocked down more than 100 campus trees in 2012, it was just another in a long series of weather-related disasters here. The Mid-Atlantic clime blesses Princeton with Northern blizzards and Southern hurricanes. Strong winds, especially when the ground is soaked or limbs are caked with ice, can prove devastating: The December 1950 storm left Front Campus heaped with kindling, just as it had been after a hurricane six years before.

Limbs of older campus trees are laced with steel wires as protection against windstorms, says Devin Livi, who oversees University grounds; they safeguard not only the trees but also nearby buildings that might get battered, not to mention students strolling below. In decades past, rotting trees were reinforced with bricks and cement. When an elm at the bus turnaround was cut a few years ago, workmen found such masonry reinforcements, along with an old English bicycle someone had stuffed inside the hollow trunk.

Stanhope Elm

Planted ca. 1805–20, girth 15’ 1”

At one time listed as the largest elm in New Jersey, its capacious spread provides a scenic tunnel for cars entering campus from Nassau Street. It was one in a row of trees planted behind Stanhope Hall, presumably to mark the western boundary of the small campus.

A 1911 map of trees on Front Campus helps us see the steady toll that weather takes: Of the 50 trees then standing, only 11 survive today, almost all of them huddled near the corner by Stanhope Hall, presumably sheltered from prevailing winds.

Several aging, 19th-century sentinels have succumbed in recent years. The beloved Cedar of Lebanon at Prospect House, one of the nation’s most handsome, toppled in a 2003 snowstorm. “The manager of Prospect called me, almost crying,” remembers Jim Consolloy, grounds manager from 1989 to 2010. “He said, ‘It’s just lying there, dead!’”

If storms wreak spectacular havoc, disease is a more insidious threat. At many 19th-century colleges, elms were a great favorite, often producing a risky “monoculture” — too many trees of the same genetic type. The countless elms of Harvard Yard, for example, had to be clear-cut after a moth infestation around 1914; around the time of World War II, Dutch elm disease brought further devastation.

Princeton’s many elms have been under relentless pest and disease assault since at least 1883, when poison first was applied to them to protect against a nasty European beetle. The beloved Bulletin Elm between East College dormitory and the “Old Chapel” was felled in May 1888, five years after it died. So many elms perished on Front Campus that a big campaign of tree planting was necessary before the 1896 Sesquicentennial. The tall, slender elm that today shades the steps of Nassau Hall came a little later, about 1901.

Dutch elm disease struck Princeton by the 1940s, when 75 percent of campus trees were elms. Arborists treated them with a pump that sprayed insecticide 125 feet in the air. Treatment continues today, in different ways: For example, the mighty elm behind Stanhope Hall, planted before 1820, receives injections of a beneficial fungus nearly every year, Livi says.

All campus chestnuts died when the chestnut blight struck around 1915. Arborists are now concerned about the emerald ash borer, a beetle that has destroyed the ash trees on Midwestern campuses since arriving there from Asia in 2002. Most of Princeton’s oldest trees are ashes, including one on Front Campus that may have been seen by the Marquis de Lafayette when he visited in the 1820s. The three celebrated giants surviving on Cannon Green also are ashes. The University is researching what has been successful in controlling the beetle and will take action when it arrives, Livi says.

Campus trees also are threatened by the constant trampling they receive. “People walk over the roots at a much higher rate than in a normal public park,” says Mary Hughes, landscape architect of the University of Virginia, another of America’s great showplaces for old trees. At Princeton, Livi’s groundskeepers use an “air spade” to blow away compacted soil around historic trees, then replace it with a fluffier mix.

Unlike the grounds at Swarthmore College, for example, Princeton’s campus is not an arboretum: Trees must make way when progress demands it. Consolloy lists numerous handsome specimens removed, including a centuries-old red oak that did not survive the construction of Whitman College and the largest Chinese toon tree on the East Coast, displaced by the Richard Serra sculpture next to Lewis Library. “Over time we lost a significant number of the largest trees of their type in New Jersey,” Consolloy says.

Construction projects aside, Princeton goes to great trouble to protect its historic trees. They provide a pleasing aesthetic accompaniment to the buildings, says Glenn Morris ’72, who leads a popular tree tour at Reunions, sponsored by Outdoor Action: “They soften the architecture and frame it.” Moreover, trees remind us of our student days, even as they slowly grow craggier and thicker, much as we do. “When people come back,” Morris says, “one of the things they notice most is the growth and change of trees. That’s part of their magic.”

Cannon Green Ashes

Planted ca. 1855, girth 12’ and 14’ 11”

Cannon Green was laid out in the 1830s; the cannon was added later. The ring-count of a recently felled ash tree suggests that the three huge ash trees on the green date to the 1850s.

Stamp Act Sycamores

Planted 1765, girth 10’ 9” and 13’ 3”

Already being pointed out to tourists in the 19th century, the twin sycamores in front of Maclean House were authorized by the trustees in 1765 and came to be popularly associated with the repeal of the Stamp Act a year later. Pairs of “buttonwoods” once were a common sight in front of stately Colonial homes; few other pairs from that period, if any, remain. Though one of Princeton’s trees was damaged in a 1979 windstorm, it survived — a living link to the age of Witherspoon and Washington.

Witherspoon Hall Maple

Planted ca. 1885, girth 12’ 2”

President James McCosh was famous for planting trees on the expanding Victorian campus. Here is a gnarled survivor from his era, one of two that graced the terraces behind Witherspoon Hall. Old photographs establish that it was planted about 1885, the year that the previously scruffy field behind Witherspoon was improved for football and baseball. The nearby white pine dates to about 1905.

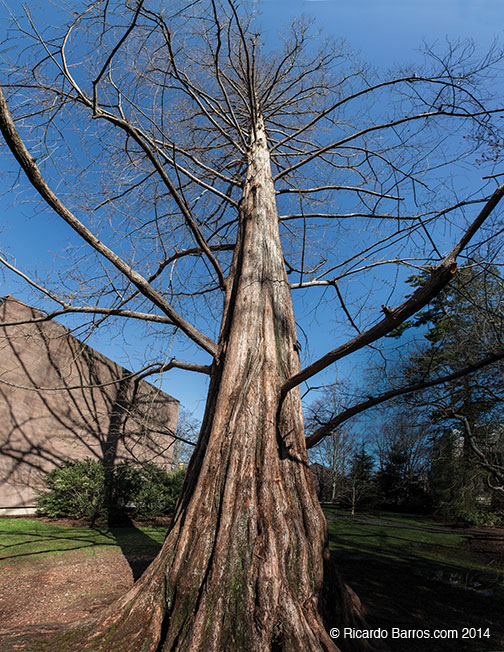

Prospect House Dawn Redwood

Planted ca. 1950, girth variable

Shooting ever higher above the McCormick Hall roof, the Prospect House dawn redwood has become one of the tallest in the United States. The species was known only from geological specimens until it was discovered alive in central China during World War II. Seeds arrived in the United States in 1948, and University horticulturalist James Clark immediately obtained some. He planted a grove of saplings along Broadmead Street near Lake Carnegie — and one here.

Today, the dawn redwood is endangered in its native range, a single Chinese valley, where the mightiest top out at 140 or 150 feet. A much smaller tree than the giant coast redwoods of California, Princeton’s Prospect tree measures about 115 feet; the tallest on Broadmead is about 117 feet.

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 is a lecturer at Princeton and the author of six books about history, including Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency and Princeton: America’s Campus.

2 Responses

Kenneth McCarthy ’81

10 Years AgoTrees of Princeton

I loved the recent attention paid to the most distinguished residents of the Princeton campus (“Our Unforgettable Trees,” feature, May 14). Maggie Westergaard’s video on the same subject, which is on the University’s website, is also outstanding.

I tried to come up with something clever to say about the relative merits of trees vs. students, alumni, and faculty, but I can’t outdo George Bernard Shaw on the topic: “Except during the nine months before he draws his first breath, no man manages his affairs as well as a tree does.”

We would do well to learn from them and reflect that they make our lives possible, not the other way around. They’re much more than ornaments.

Anonymous

10 Years AgoFor the Record

PAW neglected to provide credit for the historical photos that ran with the May 14 feature, “Our Unforgettable Trees.” They are from the Princeton University Archives.