P.G. Sittenfeld ’07 Has Reached a Verdict

The former rising political star is forging a new path but awaits an appeal ruling that could send him back to prison

ONE OF THE MOST SIGNIFICANT legal cases in a generation centered on the role of money in politics has been simmering relatively unnoticed in America’s heartland. That appears about to change. The case all started with a telephone call.

Alexander P.G. Sittenfeld ’07, a precocious star of Cincinnati politics, saw his friend’s name pop up on his phone and he answered the call. “Chin, congratulations, brother.”

Chinedum (Chin) Ndukwe had played safety for the Cincinnati Bengals. Now he was a developer pursuing projects downtown, and he was a new father.

“Hey, is Mayor Sittenfeld available please?” Ndukwe teasingly replied.

Sittenfeld’s mayoral ambitions were no secret. As the friends chatted in late October 2018, he hadn’t announced a run yet, though he was already seeking contributions from donors like Ndukwe. That he would win the election in 2021 was a foregone conclusion around town. His rise in city politics had been historic. In 2011, at 27, he became the youngest person ever elected to the City Council. Two years later, he was reelected with the most votes in a crowded field, a feat he repeated in 2017. Both times he also got more votes citywide than the mayor. His attempt to vault into the U.S. Senate in 2016, at 32, got no further than the Democratic primary in Ohio, but state Democrats saw in him a future contender for higher office.

Sittenfeld confided to Ndukwe that he and his wife, Sarah, a radiation oncologist, hoped to become parents soon, too. Ndukwe got to the point of his call. One of his development deals was heating up, known as 435 Elm St., a blighted property across from the convention center. His out-of-town investors might also contribute money to Sittenfeld’s campaign. Would Sittenfeld like to meet them?

So unfolded the first scene in an elaborate set-up devised by federal prosecutors and FBI agents that enveloped Sittenfeld until he was indicted in November 2020 on six counts of corruption. His lawyers likened it to a “prosecutorial Truman Show.” The featured players included Ndukwe, who had agreed to record phone calls with Sittenfeld after investigators uncovered previous campaign finance violations by Ndukwe. There was also a trio of undercover FBI agents posing as real estate investors, known by their aliases: Rob Miller, Brian Bennett, and Vinny. The agents kept hidden video cameras rolling when they met Sittenfeld in a penthouse apartment they rented downtown and in a hotel in Columbus. Miller always had a perfect five o’clock shadow and wore a lot of gold jewelry, a lobbyist testified. Vinny lived in Newport, Rhode Island, and liked to sail his yacht to Miami. “They just didn’t look the part,” the lobbyist recalled. “Something felt off about them.”

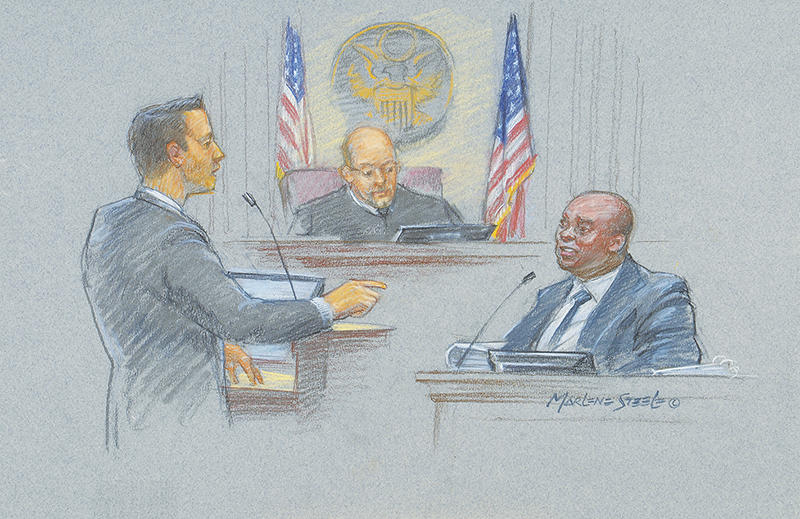

Sittenfeld maintained his innocence and testified for four hours at the trial in July 2022. The jury acquitted him of four charges. The two guilty verdicts involved accepting $20,000 from the FBI agents for his political action committee in a quid pro quo of support for Ndukwe’s project.

This past January, Sittenfeld, by now 39 and the father of two young sons, reported to a minimum-security federal prison camp in Ashland, Kentucky, to begin serving a 16-month sentence. He joined daily Bible study and gave sermons in the chapel. He became expert at making cheesecake improvised from commissary items, slices of which he distributed to fellow inmates. He also busied himself writing long-form profiles of his new brothers-in-confinement, dusting off the craft he had practiced at Princeton in a seminar taught by John McPhee ’53. His prison job was to assist an inmate known as the “Mayor of Ashland” in daily rounds of checking fire extinguishers, preparing beds for new arrivals, and troubleshooting inmate needs. In one of his regular prison dispatches, which one of his older sisters, the bestselling novelist Curtis Sittenfeld, shared weekly with family and friends, Sittenfeld wrote: “It’s not lost on me the irony that I didn’t become the Mayor of Cincy but here I am serving as the ‘chief-of-staff’ to the ‘mayor’ of the Ashland camp.”

Meanwhile, the federal appeal of his conviction started drawing national attention. After that initial phone call, the agent running the operation instructed Ndukwe to make an explicit illegal offer, according to testimony. A week later, Ndukwe was on the phone saying to Sittenfeld, “For this meeting with Rob next week, I’m pretty sure he can get you 10 this week. You know the biggest thing is, you know, if we do the 10, I mean, they’re gonna want to know that when it comes time to vote on 435 Elm … that it’s gonna be a yes vote, you know, without, without a doubt.”

Sittenfeld replied: “I mean, as you know, obviously nothing can be illegal like … illegally nothing can be a quid, quid quo pro. And I know that’s not what you’re saying either.”

In the next breath, Sittenfeld added: “But what I can say is that I’m always super pro-development and revitalization of especially our urban core … . In seven years I have voted in favor of every single development deal that’s ever been put in front of me.”

That’s the heart of the matter. When does a politician informing a donor of his values and priorities cross the line to making an illegal promise?

A bipartisan array of former federal corruption prosecutors, former Justice Department officials, retired elected officials, and civic and business leaders have signed legal briefs supporting the appeal by Sittenfeld, a Democrat, calling the case “a conviction for conduct that was not criminal,” in the words of the prosecutors’ brief. The briefs warn that if his conviction stands, it will undermine the First Amendment by criminalizing routine daily interactions between politicians and supporters. The brief-signers include former Republican Attorneys General William Barr (criticizing an indictment brought by his own Justice Department), John Ashcroft, and Michael Mukasey; Gregory Craig, White House counsel under Barack Obama; Donald McGahn, White House counsel to Donald Trump; Mike McCurry ’76, former White House press secretary for Bill Clinton; and Carter Stewart, former U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Ohio, an Obama-appointed predecessor to the Trump-appointed U.S. attorney who indicted Sittenfeld and the Biden-appointed U.S. attorney now opposing his appeal.

Sittenfeld was not permitted to attend oral arguments in May before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. Sarah, his wife, and other family members sat in the front row. Less than a week later, in an unusual twist, the three-judge panel that heard the arguments ordered Sittenfeld released after he had served fewer than five months, pending their final decision. The judges cautioned that the move should not be taken as a signal of their ultimate opinion, but it showed the case raised “a close question” that could result in the conviction being reversed. The court’s decision could land anytime. Whichever way it goes, lawyers following the case say, it is poised to have a decisive impact on the way politics is practiced, and the Supreme Court may get the final word.

For the man at the center, the impact has already been dramatic in surprising ways. “The last 3½ years … have felt first like a profound spiritual journey; second, like a love story; and only third, like a legal nightmare — in that order,” Sittenfeld told PAW in an email a few days after he was released. “When you plug all three of those in, at least from me, you get an expression of gratitude.”

Now Sittenfeld finds himself in the unusual position of fighting for a legal principle that, even if he prevails, he no longer cares to take advantage of. He has set aside his political dreams — “I will not be running for elected office,” even if his conviction is overturned, he says — and plans to try working as a writer. In his letter to the judge before his sentencing, he wrote, “Do I want to put these shattered and broken pieces of my life back together as they were before? My answer, Your Honor, is a profound no — and there has been a dramatic reordering of my ambition.”

Instead, he has begun a different journey. Shortly after his conviction, he confided to friends, “I pictured myself, on that day of my arrest, sitting in handcuffs in the backseat of an FBI vehicle. What would it mean for my worst moment — one of humiliation, fear, and despair — to have, in fact, represented something radically different and to have contained the seeds of something greater?”

“The biggest goals for my life are I want to be a deeply involved husband and father, and I want to be a committed Christian. And then, if I’m doing those two things, let whatever worldly path unfold.”

—P.G. Sittenfeld ’07

Alex Derkson was the new kid in seventh grade at the private Seven Hills School in Cincinnati in 1997, sitting uncomfortably alone at a backyard pool party for members of the class. He spied one of the most popular boys sauntering in his direction. “And P.G., you know, gregarious guy, came and started talking to me and just asked me questions and introduced me” to other kids, he recalls. “He loved to connect people; he loved to make people feel welcome.”

Everyone who knows Sittenfeld says this is a defining trait, evident throughout his life — even on the undercover FBI tapes. The recordings feature Sittenfeld urging one of the agents, in the first hour of their acquaintance, to find a wife and settle down in Cincinnati and offering to set him up on a blind date. He tells the agents they can stay at his house if their apartment gets too small. He invites them to a dinner party at his home with the then-U.S. attorney, whose office at that moment was investigating the host.

Sittenfeld attended Princeton in the footsteps of his father, Paul G. Sittenfeld ’69, an investment manager in Cincinnati who died of a sudden illness four months after his son was indicted, and his older sister, Josephine Sittenfeld ’02, a professional photographer. His third older sister, Tiernan Sittenfeld, is an executive with an environmental advocacy group.

“P.G. was the type of student that kind of everyone knew and was friends and friendly with everyone,” says Danny Shea ’07, one of Sittenfeld’s roommates in Forbes College. “P.G. in the freshman dining hall, this was kind of like a creature in their habitat. Will talk to anybody, can talk to anybody.”

After being elected president of the freshman class, he migrated from politics to journalism, writing columns for The Daily Princetonian and PAW, and became president of the University Press Club. When his sister Curtis’ literary career soared with the publication of her novel Prepin 2005, he published a satirical Q&A with her in the Prince on the eve of her reading in McCosh 10:

“P.G.: As you prepare to come speak on campus, do you feel residual insecurity about the fact that Princeton rejected your undergraduate application back in 1993?

“Curtis: It did sting at first. But I got over it after I ghostwrote your application and ‘you’ were accepted. Now that I ghostwrite this column as well, I feel like a really valued member of the Princeton community.”

After Princeton, everyone assumed he would return to his beloved Cincinnati, probably to launch a career in politics. When he won a Marshall scholarship to study at Oxford, “I was surprised, not because he’d won a prestigious honor, but because spending two years in Oxford would delay his return to the city that he’d just spent the last four years describing as the greatest place on Earth,” Shea says. “There are two things for sure that he would have talked about to anyone who would listen, which were Skyline Chili and Graeter’s Ice Cream.”

The choice between careers in politics and writing was actually a closer call for Sittenfeld than it may have appeared. “Politics won out for that chapter, but only by a little bit,” he said in a telephone interview from the prison camp, on the day before his release, when that plot twist had yet to be revealed.

Before turning to politics, he worked for a couple years for an education nonprofit in Cincinnati. To call his first campaign for City Council energetic would be an understatement. “He set the city back on its heels — you know, ‘Who’s this Sittenfeld guy?’” says former Cincinnati Mayor Mark Mallory. “The way he thinks is, ‘I’m going to go out here and appeal to as many people as I can, regardless of their race, regardless of their social status, regardless of East Side or West Side.’”

In addition to being known as a sure vote on development projects, Sittenfeld became a champion of enhancing services for senior citizens, building affordable housing, and improving pedestrian safety. In 2018, he and four other councilmembers were in a power struggle with then-Mayor John Cranley. It emerged that the five were communicating by text, a violation of open meeting laws that embroiled the city in a bitter $101,000 lawsuit. Sittenfeld called the text thread an “honest mistake” in a statement of apology at the time.

By July 2020, when Sittenfeld announced his run for mayor, the FBI was deep into its investigation of what prosecutors called a “culture of corruption” in Cincinnati. In November 2020, Sittenfeld became the third member of the City Council indicted that year, following his colleagues Tamaya Dennard and Jeffrey Pastor.

Sittenfeld’s supporters maintained that the cases were categorically different. Dennard and Pastor pleaded guilty to accepting money for personal use. Sittenfeld pleaded not guilty to improperly taking contributions that he reported to the elections officials. But some in Cincinnati were not ready to draw such distinctions. “If you read the indictments of Tamaya and Jeff, and P.G., they’re all bad,” Cranley said at a news conference hours after Sittenfeld was arrested. “It’s hard not to conclude that, in Tamaya and Jeff’s case, at least part of it was desperation for cash. In [Sittenfeld’s] case, it seems to be to accumulate power for power’s sake. And so, in many ways, that’s worse. But it’s all bad. It’s all sickening. It’s all depressing.”

Sittenfeld had been informed of his impending indictment the day before. He told Sarah. “I say this news that must seem sort of like more than just shocking, sort of like unthinkable and confusing and foreign and unleash a million scary questions,” he recalled in the interview from prison. Her reaction was to take his hand and say, “For better or worse.”

In the interview, Sittenfeld continued, “For someone to so instinctively live the [marriage] vows in that moment is the most touching, loving gesture I’ve ever been on the receiving end of in my entire life.”

The set of the so-called Truman Show in which Sittenfeld played the antihero fits within several blocks of downtown Cincinnati. Here is the bustling Mexican restaurant Nada, where Ndukwe introduced Sittenfeld to agent Rob Miller over lunch, and where, before the black beans and rice were cleared, Sittenfeld whipped out PowerPoint slides to demonstrate his broad political support, “in the event that, um, Chinedum is successful in twisting your arm to be supportive of someone” in the mayor’s race. Across the street is the swank apartment building where Miller invited Sittenfeld after lunch and offered $10,000 in cash, which Sittenfeld declined because, he said, so much cash was an irregular way to make a campaign contribution. Several blocks away is 435 Elm, still a hole in the ground next to an adult entertainment boutique as of early June. Farther along is City Hall, built in classic Richardsonian Romanesque style that makes it look like a swollen Alexander Hall, where Sittenfeld once hoped to preside. Conveniently close at hand are Skyline Chili and Graeter’s Ice Cream.

The words are not in dispute. They’re all on tape. The question is: What do they mean? Prosecutors, led by Assistant U.S. Attorney Matthew Singer, highlight something Sittenfeld told Ndukwe in another conversation. Ndukwe, a regular contributor to Sittenfeld, said he was reluctant to donate now because he wanted to stay on the good side of Sittenfeld’s political opponents. Sittenfeld said it would be fine if Ndukwe simply helped raise money from others, which is legal. Sittenfeld continued, “But I mean the one thing I will say is like, you know I mean, you don’t want me to like be like, ‘Hey Chin like love you but can’t.’”

Ndukwe testified that he interpreted that to mean, “If I donated, he was going to support and be supportive in my efforts, and if I didn’t, he wasn’t going to be supportive.”

In his own testimony, Sittenfeld countered that the context of the conversation was his effort to become mayor, not any specific project. If he weren’t elected mayor, he couldn’t act for Ndukwe or anyone else in the city. “I know what I was thinking, I know what was in my heart,” Sittenfeld told PAW. “And, you know, as I said on the stand, I would never in a million years have taken a bribe for a vote. That’s not why I went into public service.”

Prosecutors also highlight a moment in the apartment when Sittenfeld told agent Miller, “I can sit here and say I can deliver the votes.” Earlier at Nada, and later at another meeting, he said he was ready to “shepherd the votes.” Prosecutors argue that even though Sittenfeld rejected the obvious quid pro quo from Ndukwe, he still knew what the faux developers wanted and that they were willing to donate $20,000. “The jury rationally found that this was not evidence of ‘ordinary politics’ but evidence of an explicit quid pro quo,” prosecutors wrote in their brief against Sittenfeld’s appeal. (Prosecutors declined PAW’s request to comment.)

Sittenfeld’s pro bono lawyers — led by James Burnham and Yaakov Roth — cast the exchanges in a different light. They point out that Sittenfeld had supported redeveloping 435 Elm before he met the agents. His offer to “shepherd the votes” came after he asked a series of questions about the project, and Ndukwe and agent Miller painted a rosy picture of a hotel, offices, stores, and apartments. On the tapes, Sittenfeld sounds mystified that the developers think anyone would oppose such a project, including the mayor, “if this project is what it is teed up to be.” “The idea that they had reached some sort of illicit trade for money, and then he’s pulling out PowerPoint slides half an hour later to make a pitch, just doesn’t make any sense,” Roth told the appeals court. “He’d already committed to this on the merits and without any discussion that it was conditional in any way.”

It took the FBI agents six weeks to give Sittenfeld the $20,000 in part because they kept offering it in forms that could have violated political contribution laws if Sittenfeld had accepted. First they tried cash. Then money orders. Then corporate checks. Finally Sittenfeld accepted checks from duly registered limited liability companies to his political action committee.

Catherine Turcer, executive director of Common Cause Ohio, a government accountability advocacy group, says the case shows how blurry the line between legal and illegal behavior has become — but she says Sittenfeld crossed it. “What P.G. Sittenfeld did was a violation of the public trust,” she says. “He told undercover agents that he could ‘deliver the votes.’ That’s not exactly the same as, ‘I will do this if you will do that,’ but it’s very clear. And what’s really scary is, if that’s not clear, well, then how do we ever prove that the public trust is being violated?”

Kenneth Katkin ’87, a professor of constitutional law at Northern Kentucky University who attended the proceedings out of professional interest and to offer commentary for Cincinnati news media, says Sittenfeld’s case is different. It’s one of few federal prosecutions in decades for bribery in the form of legally reported campaign contributions as opposed to cash or gifts for personal use. It’s also “extremely unusual to see so many [former] prosecutors of both political parties saying that a political corruption conviction, or really any kind of criminal conviction, was a wrongful conviction,” he says.

America’s privately funded democracy requires politicians to be able to raise money based on what they have done and will do, Katkin says. Voters, in turn, must be able to give support based on that record and those promises. “What [Sittenfeld] did not only wasn’t illegal, it wasn’t different than what every other elected official does,” he says. “Any politician who says, you know, ‘I’m going to vote to enact a Roe-versus-Wade law and restore abortion rights nationally, so give me money and help me get elected so that I can do that,’ and then people give him money … . That could be seen as bribery under the theory that’s used in this case.”

“What P.G. Sittenfeld did was a violation of the public trust. He told undercover agents that he could ‘deliver the votes.’ ... If that’s not clear, well, then how do we ever prove that the public trust is being violated?”

— Catherine Turcer, executive director, Common Cause Ohio

On the morning of his 21st day of provisional freedom, in early June, Sittenfeld is still sporting the sharp haircut he got in exchange for eight tortillas from a prison buddy inside Ashland. After a stroll through a park and past the Catholic church where he worships and volunteers, he settles in for coffee at a nearby café. The “seeds of something greater” that he once prayed might lie within his lowest moment have started to germinate.

“You think your life in the world is, ‘What’s my résumé? What’s my diploma? What’s my job? What’s my income? How do I look?’” he says. “I do not believe those things are my identity now.”

He continues, “The biggest goals for my life are I want to be a deeply involved husband and father, and I want to be a committed Christian. And then, if I’m doing those two things, let whatever worldly path unfold.”

Sittenfeld would not be the first person convicted of a felony to embark on a more intense spiritual path while asking hard questions about the purpose of life. But even before his indictment he was pondering what lay beyond the daily slog and frenzy of political striving. He says he was moved by the story of Cyrus Habib, a rising star of Washington state politics who chucked his career to enter the Jesuit religious order. After his indictment, Sittenfeld sought out Habib, who has become a friend and spiritual mentor. Habib introduced him to the concept of recognizing the “invitation” in struggle and suffering.

Now, even as he battles for legal vindication, Sittenfeld says he can’t help seeing himself as someone who has been granted the “gift” of appreciating his life in deeper ways, albeit at great personal and professional cost. It’s made him think about returning to the road not taken after Princeton. He says he wants to tell stories, advocate, offer his experience as a comfort to others caught in crises and searching for meaning. “I am more interested in the hearts-and-minds approach to change, rather than pulling-the-levers-of-government approach to change,” he said in the interview from prison.

“If the universe allows me to, I would like to help tell powerful stories that maybe cause people to look more closely at something or change their mind about something or be introspective in a way that kind of helps them lead a better life.”

He added: “There’s been way too much that’s been beautiful and meaningful and redemptive in this journey for me to just say, ‘Well, we live in a cruel, hard world where nonsensical or unfair things happen, end of story.’ The story’s not over; the story’s still unfolding. And there are things, beautiful things, that are yet to happen.”

David Montgomery ’83 is a freelance journalist and former staff writer for The Washington Post Magazine.

10 Responses

D. Verne Morland ’74

6 Months AgoThe Sabotage of a Promising Political Career

As a resident of Dayton, Ohio, (55 miles north of Cincinnati) I became aware of P.G. Sittenfeld ’07 not long after he was elected to the Cincinnati City Council. Noting that he is a fellow alumnus, I followed his rising political star with interest, especially because everything I read about him suggested that he was in politics for all the right reasons. Sure, power, prestige, and personal ambition were factors as they always are in the political arena, but when I read about the programs that he championed and supported it was clear that he truly had the best interests of Cincinnati and all of its citizens at heart. When he ran for a seat in the U.S. Senate in the Democratic primary in 2016, I voted for him.

That being the case, I was very disappointed to learn about his indictment and subsequent conviction on two of the six charges against him. “Corruption” is such an ugly word, and I have a basic faith in our justice system.

This article helped me understand the circumstances surrounding this case and it saddens me greatly that such a talented and well-intentioned young man and his family were so unfairly treated by the authorities. I understand and agree that undercover “sting” operations are necessary in many circumstances to gather evidence against criminals, but this case is clearly a case of law enforcement and prosecutorial overreach.

P.G. is remarkable in many ways, not least in his positive attitude about the lessons of this horrific experience. I wish him well in his future endeavors as a writer and I have every confidence that he will succeed. That said, I remain very disappointed that the citizens of southwest Ohio, our entire state, and possibly the nation have lost a very capable and well-intentioned young politician. In these troubled times, we need more leaders like P.G. Sittenfeld.

Rignal W. Baldwin Sr. s’72

6 Months AgoSpecial Attention Not Warranted

What would otherwise be a garden variety criminal matter, with all of the usual imperfections, inequalities, and claims of innocence, is a matter of significance to PAW presumably because of the defendant’s PU and political pedigree. The article notes support from “[a] bipartisan array” of heavy hitters with considerable influence. He has assembled an impressive lineup.

Many real and perceived injustices occur every day (every hour) in our courts, from the current Supreme Court down through the trial courts. The difference here is an inherent financial and political advantage that enable the defendant to tell his version to your audience. The defendant and his story do not deserve special attention. It was a poor editorial decision, tone deaf as to the many unfair advantages of privilege and access.

Robert H. Golden ’61

7 Months AgoVictim of Entrapment

On page 50 of your July/August 2024 issue, Alexander P.G. Sittenfeld ’07 is the victim in a classic case of entrapment, which should have been dismissed.

Dave Lewit ’47

8 Months AgoParallels to Another FBI Operation

The editors of PAW are courageous to publish the lengthy story of Cincinnati city councilor P.G. Sittenfeld ’07’s prosecution for alleged corruption, considering likely criticism by some alumni. P.G.’s story is emblematic of bureaucratic culture and ambition, reminding me of Melville’s classic Billy Budd.

Sittenfeld was subjected to an FBI sting operation and spent time in a federal prison for granting faux petitioners that he supports and would continue to support downtown real estate development. But the petitioners were trained FBI “witnesses” who pressured Sittenfeld, contributing money to his action fund.

In 2010, I sat through most sessions of Boston city councilor Chuck Turner’s very similar trial for “corruption.” Indeed, the FBI remunerated the “petitioner” $20,000 to pass an alleged $1,000 in cash to the councilor, who was renowned for ordering hearings on constituent issues. The Boston Herald vilified Turner by publishing on its front page a fuzzy photo, taken from the hireling’s hidden video camera, of the passing of cash — never actually counted ($50 is permitted to councilors). The eminently diligent Turner consequently spent 28 months in a federal prison in West Virginia, far from his constituents.

The only Black councilor, Turner had been singled out, falsely, to be tied to a Black state senator who had admitted to taking money for favors. The judge forbade the jury to characterize the sting as entrapment. Who is guilty? It seems that Turner’s and Sittenfeld’s fates are fruits of government corruption.

Edward Burke *67

8 Months AgoHow Should a Politician Interact With Constituents and Donors?

I read “P.G. Sittenfeld ’07 Has Reached a Verdict” (July/August issue) with the greatest interest. I am impressed that the magazine ran the article. Many alumni magazines would shy away from this kind of story. I was a member of the Massachusetts Senate from 1971 to 1993. As I read the article, I had all kinds of memories of deciding whether to accept certain campaign contributions and whether to make a commitment to a bill or project even without knowing all details and fine print. Sittenfeld’s emotional support from his wife is impressive. Politics can take a heavy toll on family life.

James Corsones ’75

8 Months AgoWhy Become a Politician?

After reading the article about P.G. Sittenfeld ’07, I am left with the impression that nobody with any scruples would want to be a politician. It seems that the supposed friend was in trouble and somehow got the FBI to go after Mr. Sittenfeld instead. The whole game of politics has become so corrupt that any reasonable person should wonder if the specter of doing something for the “common good” is worth the price one has to pay to be nominated or elected.

Until the recent change in the candidacy for president, one could have reasonably wondered if there would have been any chance to be able to follow Princeton’s motto in the modern political sphere.

Lemoine Skinner III ’66

8 Months AgoAn Inspiring Story

Ethical rules require us often to walk this line. What an abuse of discretion to have prosecuted P.G.

Linda Beuret s’60

8 Months AgoArticle Needs More Explanation of Why Investigation Began

I’ve read and reread the Sittenfeld article in the Alumni Weekly. My question is what started this investigation? Why is the government investigating him in the first place? Did some political rival start this process? From what your reporter tells, I do not see how they can say that he did anything wrong at all, as long before this occurred he had stated that he was in favor of downtown development. As the reporter points out, it is like my support of a pro-abortion politician because I have heard him say he is pro-choice.

Michael York

8 Months AgoFantastic Piece

Thanks so much for your dedication, reporting, and sensitive writing for this complicated piece.

Textbook case of how to write about a textbook case.

Alex Heldman

8 Months AgoA Balancing Act for Lady Justice

This was a very well-written unbiased story. I enjoyed reading it immensely.

Democracy dies in light and darkness.