Almost a year before it was impossible to have a conversation without mentioning a certain virus, social distancing, symptoms, or vaccines, curators Laura Giles and Veronica White ’98 at the Princeton University Art Museum were developing a new exhibition that would, among other things, “examine societal anxiety around pandemics and infectious disease.”

Their exhibition, “States of Health: Visualizing Illness and Healing,” premiered Nov. 2, 2019, and closed three months later — just two weeks after the first case of COVID-19 in the United States was confirmed and more than a month before the University would ultimately send students home and move classes online. It featured more than 80 pieces of art that spanned the globe, time, and states of health.

On Nov. 20 at 2 p.m., the curators will reconvene for a virtual panel discussion, “Picturing Pandemics: From the Distant Past to the Recent Present,” in which they will examine objects in the museum’s collections that address the topic, ranging from items created in the ancient Americas to those produced in contemporary times. To participate and view all the images that were in the exhibition, go to bit.ly/picturing-pandemics.

Update: View a video of the panel discussion at artmuseum.princeton.edu.

“Over these centuries, humans have turned to art, and the visual arts have provided a means of coping, of expressing throughout these pandemics,” says White. “There’s something heartening about that, in a strange way.”

Giles adds, “There’s a tremendous amount of beauty in this exhibition, and beauty is healing.”

Anna Mazarakis ’16 is a podcast producer.

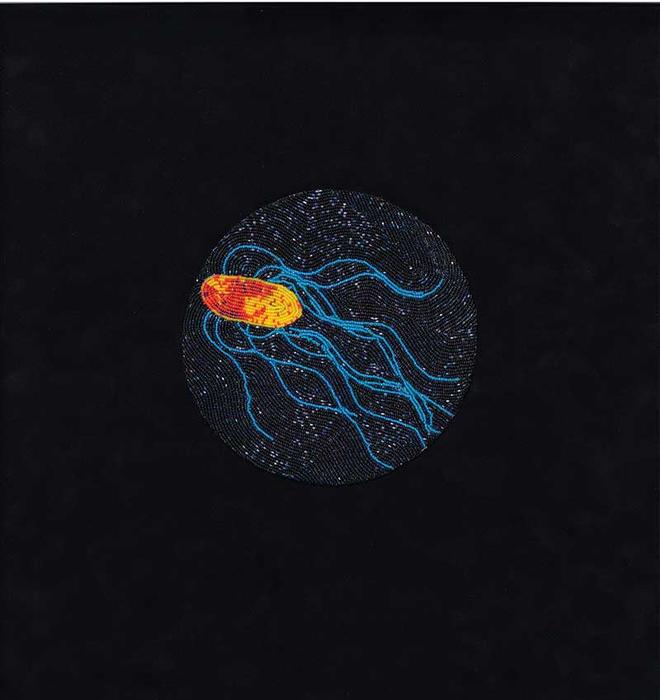

Reserving: Typhoid Fever (above)

Ruth Cuthand (2018)

Ruth Cuthand, Canadian, born 1954, Reserving: Typhoid Fever, 2018. Glass beads, thread, backing. Princeton University Art Museum purchase. © Ruth Cuthand.

When European colonizers came to North America, they ended up trading goods like beads and not-so-goods like infectious diseases. The Native population would be devastated by high rates of infection and death.

Ruth Cuthand, a Canadian citizen and member of the Plains Cree nation, examines those two imports in her series “Reserving.” She creatively reimagines microscopic views of the deadly diseases that affected First Nations in Western Canada from the signing of a treaty in 1879 that would relegate the Cree, Assiniboine, and Ojibwa nations to reservations, to the discovery of HIV in 1983.

This image, which the museum acquired for this exhibition, depicts an enlarged microscopic view of typhoid fever using glass beads like the ones the colonizers would have brought with them. Giles described the work as “terrifyingly beautiful.”

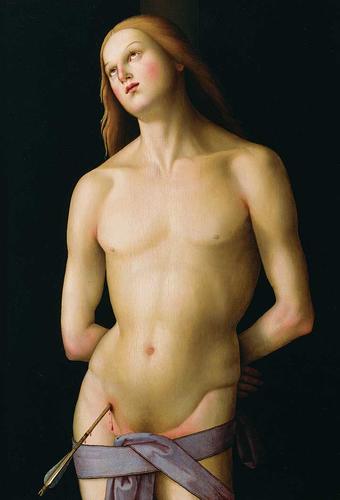

Saint Sebastian

Master of the Greenville Tondo (ca. 1500–1510)

Those who suffered from the bubonic plague likened the pain to being pierced with arrows. So when Saint Sebastian, an early Christian martyr, was shot with arrows by order of the Roman emperor and survived, he earned another legacy as a figure who could protect or heal against that infectious disease.

In this piece, Saint Sebastian is looking up as an arrow is lodged in his groin, which is where pustules of the plague were known to form. Bathed in light, Saint Sebastian is depicted as a divine being while he suffers from the pain of the arrow. His resolve through pain led people to pray to his image for hope, healing, and protection.

“This idea of suffering, of perseverance and hope — there are different objects for prayer or for comfort that people turn to during times of illness,” says White. “I think that’s a tradition that continues across cultures.”

Untitled, from the Sex Series

David Wojnarowicz (1989)

The symbolism of Saint Sebastian reemerged during the AIDS epidemic as he became embraced by the LGBTQ community. In this photomontage, Saint Sebastian is pictured within a peephole, alongside pictures of blood cells, money, and people in the midst of intimate sexual acts. Those peepholes cover a photograph of a tornado that is superimposed by newspaper clippings. The montage is meant to highlight powerful natural and human-made forces.

The piece was controversial, as it led to a debate over pornographic images and whether the message was appropriate for display in a public museum. Wojnarowicz, who was diagnosed with AIDS shortly before making this piece, was also outspoken in his criticism of the United States government in its response to the AIDS epidemic.

“It’s really hard not to tear up,” Robbie LeDesma says about taking in the piece. He’s a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate in the molecular biology department who consulted on the exhibition. “Knowing the emotions that went into them and knowing how the artist did end up eventually succumbing to his illness was just ... heartbreaking.”

Stay Woke

Mario Moore (2018)

When we think of infectious diseases and pandemics, images of bacteria or depictions of illness come quickly to mind. Yet the world was also confronted with images of a pandemic of a different sort this year: structural and systemic racism. Museum curators foreshadowed that struggle, too, by featuring pieces like Mario Moore’s “Stay Woke” in the mental-health section of the exhibition.

Moore created his “Stay Woke” series after he had to stay awake while undergoing brain surgery. The series shows the “two-sided mental state that Black men face,” wrote Moore: They’re at rest, but also prepared for action. In his self-portrait, Moore appears ready for sleep but he’s also fully dressed, with a gun under his pillow.

“It was his way of using art as therapy,” says Giles.

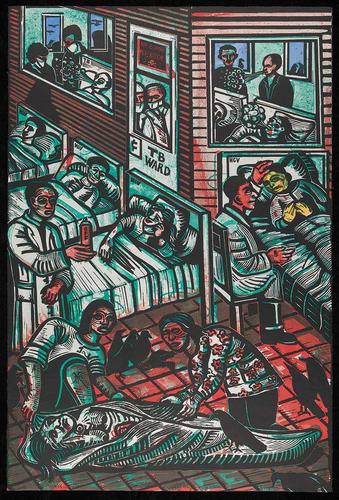

Emerging Infectious Diseases

Eric Avery (2000)

As an artist and physician, Eric Avery creates works that serve both as educational tools for patients and visually appealing pieces of art. “His approach to art is a good way, and actually a smart way, that you can get people to understand complex concepts,” says LeDesma.

In this piece, Avery reworked a 16th-century woodcut that depicted clergy taking care of sick patients in a church by substituting doctors and a hospital’s infectious-disease ward. A close observer would notice many details, including that one of the doctors in the foreground is holding a can of insect repellent since he’s treating a patient with West Nile virus, which is transmitted by mosquitoes. Another patient has yellow-tinged skin, which those in the know would recognize as jaundice, a symptom of the hepatitis C virus.

“There are just so many small details that are just so incredible,” LeDesma says, noting that a lay observer might just look at the painting as a whole and think it’s pretty without recognizing the numerous details.

A curious herbal, containing five hundred cuts, of the most useful plants, which are now used in the practice of physick . . .

Elizabeth Blackwell (1739–51)

Before the rise of modern medicine, treatments for various diseases and ailments came in the form of plants that were known to have medicinal properties. While men dominated the field, one woman stood out: Elizabeth Blackwell. She produced this book with support from the English Society of Apothecaries in an effort to release her husband from debtors prison. While her physician husband wrote the text, Blackwell singlehandedly engraved the copper plates and drew and hand-painted each of the hundreds of plants.

“It’s one of the most visually stunning books I have ever seen — it might be my favorite book in the world,” says LeDesma.

During the exhibition, the book was opened to the page featuring the white opium poppy, a tribute to the opioid epidemic that is ongoing in the United States. The book described the plant as “an excellent medicine in the hands of a wise man,” but warned that it shouldn’t be prescribed by anyone else since its use had resulted in many fatal accidents. That warning came hundreds of years ago, but it’s just as relevant now.

The Cow-Pock – or – the Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation!

James Gillray (1802)

“I don’t like it, actually, at all,” says LeDesma of James Gillray’s satirical commentary on the pioneering smallpox inoculation. At the turn of the 19th century, Dr. Edward Jenner found that a person could become immune to smallpox by introducing pus from a sore on a cow to an open wound. The Latin word for cow — vacca — would serve as the root word for vaccine.

In this piece, Jenner is depicted as cutting into a patient’s arm to vaccinate her, while other vaccinated patients around her have begun to grow, vomit, and even birth miniature cows. LeDesma says it’s the oldest piece of anti-vaccination propaganda he’s seen.

“A lot of these things are playing on people’s fear of the unknown,” he says, noting that fears surrounding vaccines continue today. Smallpox was eradicated in 1980, a testament to the effectiveness of the vaccine.

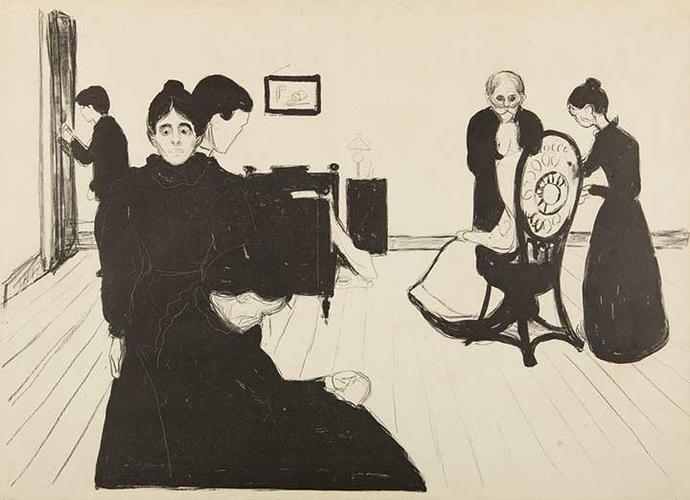

Death in the Sickroom

Edvard Munch (1896)

Edvard Munch is best known for his piece The Scream, and his piece in this exhibition might provide some insight into a private despair. This image shows Munch’s memory of the moment his sister died from tuberculosis, when she was 15 years old and he was 14.

“It’s probably one of the more harrowing images in the show,” says Giles.

His sister is sitting with her back to the viewer, and though she’s surrounded by her family, each family member is standing alone rather than offering comfort to another. Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that ravaged northern Europe in the late 19th century, and deathbed portraits like this one weren’t out of the ordinary at the time.

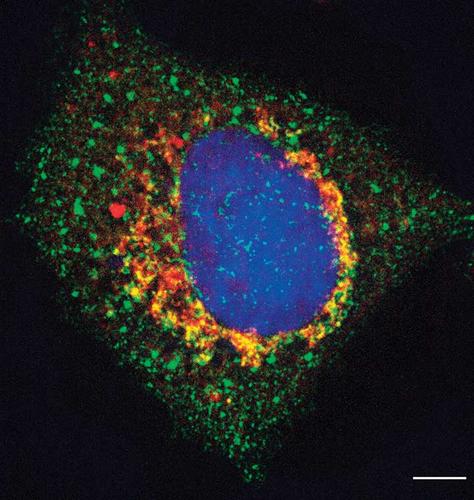

Flat screen with microscopic and structural level images of diseases

Cora Betsinger GS (2018), at right, and various Princeton labs (2010–2019)

Every illness starts with a tiny cell. The effects on the human body can be seen and felt, but it takes a scientific eye to understand exactly what is taking place. For centuries, scientists have put cells under a microscope to figure out how they work and how they can be prevented from doing further damage. It turns out that the microscopic world is very visually interesting, too.

The exhibition featured an installation of images of pathogens that are currently being studied in laboratories across campus, including those that cause infectious diseases like cholera, hepatitis C, and HIV. LeDesma collected the images from colleagues in the molecular biology department. He will speak on the November panel.

“When you’re looking at them, you see these really fluorescent and bright and beautiful images,” LeDesma says of the pathogens, “but then when you read the caption, you actually realize just the human toll that these pathogens take and how infectious they are, but also how we are actively trying to combat them.”

“Picturing Pandemics: From the Distant Past to the Recent Present,” Nov. 20 at 2 p.m. To participate and view all the images that were in the exhibition, go to bit.ly/picturing-pandemics.

1 Response

Munira I. Chudoba s*02

4 Years AgoPersonal Reflections on a Powerful Image

I am keeping it together. This is what I say to myself second time around being separated from my family, and my work, due to political and COVID-19 issues. But, not to worry, I am stuck in a good city, in a good country, and with our eldest daughter whose European first name means illuminous and her Persian second name means “quiet heart.” So, I am quiet and peaceful until I picked up this edition of Princeton Alumni Weekly.

Magazines were always something I liked reading growing up in the USSR. Smell of printed paper of a freshly printed magazine is not like decomposed old book. I liked reading hard copies of scientific and educational monthly editions. A lot of thought provoking and artistic guidance towards poetry, prose, and art would be given by critiques. My mother was the one to blame for my love with regard to art and culture. She was no ordinary woman. She was born in 1928 in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and was one of five survivors among 13 siblings. She was a woman who saw her maternal lineage burn paranji (a traditional Central Asian robe for women and girls that covers the head and body in early 20th century). She also,was a survivor of TB in her childhood. Hence, she became a doctor in this subject, and a mother of four adopted children, which we only found recently. So when I came across Princeton Alumni Weekly (November 2020), which we don’t have much opportunity to read, as my husband’s work and his love towards development work in post conflict areas and mountainious regions has taken us to Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan —to the land of nomads (actually thanks to some guidance in Princeton), I could not find my comfort spot to lean on. I stared at page 25 from the top image “Death in Sickroom” and the cover of that edition. These two images were perfect. Perfect in their small size and strength. It struck me, “so, this is what it must have been for my mother all those years ago to fight tuberculosis.” Images of fear, crying, and desperation of a young mind. Lonely and yet, so ready to start coping again.

It triggered me to use this magazine as an advertisement in Viennese subways, where one hardly sees people reading paper editions. Reading little paragraphs of eight images made my somewhat maturing motherly journey of April 2020–August 2021 momentous. I am going to call it, “I lost something and I gained more.”

Thank you for this fantastic opportunity to remind myself where my life started: my mother.