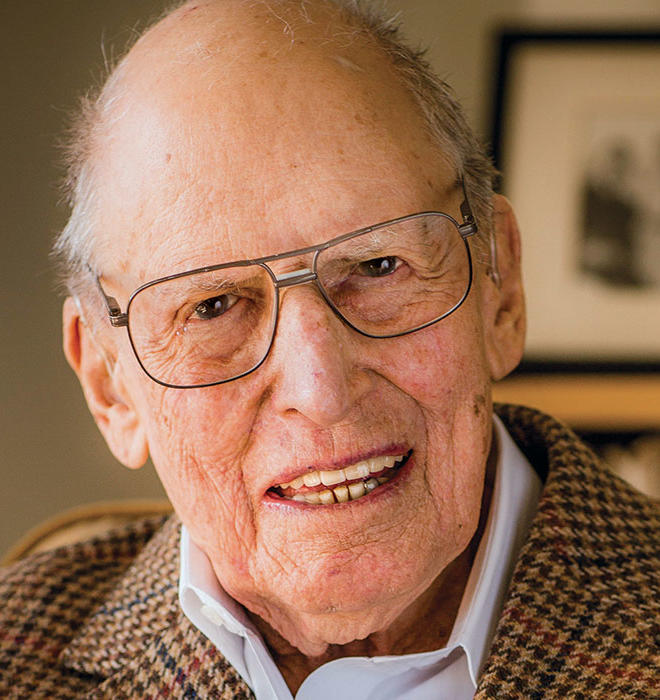

Editor’s note: Henry Morgenthau III ’39 died July 11, 2018, at age 101. Read an obituary in The Washington Post.

Old age, they say, is not for the faint of heart — but that is a cliché. Henry Morgenthau III ’39 expresses the thought much better:

I’m telling you my dear,

dying is the most important

event in your life.

You can rehearse it

in your head and with your body.

You can prepare for it

all your life,

you can only do it once,

there is no looking back.

You can never ask,

“Did I do it well?”

You will never know.

No one will know.

It will be said,

“Surrounded by his loving family,

he died peacefully.”

Cold comfort for the warm-blooded:

a sugar-coated lie.

The poem comes from Morgenthau’s A Sunday in Purgatory (Passager Books), his first collection of poetry, published just before his 100th birthday in January. The tone is by turns wistful, humorous, and occasionally angry; several poems looking back on a rich life, others staring across a tenuous present. (“Purgatory” is the Washington, D.C., retirement community where he lives.)

To spend an hour with Morgenthau is to take a stroll through a large swath of history. His grandfather was the American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. His father was Franklin Roosevelt’s treasury secretary and neighbor. As a Princeton undergraduate, young Morgenthau paid a call on Albert Einstein. As a longtime documentary producer, he worked with Eleanor Roosevelt and Martin Luther King Jr. Though he likes to talk about the work he is still doing, it is difficult to resist dragging Morgenthau back into the past, just to hear his stories.

Start with John F. Kennedy, briefly a Princeton classmate. “Oh, I had known him quite well,” Morgenthau says; their fathers both served in the Roosevelt administration. In the summer of 1938, shortly before the outbreak of World War II, both families vacationed at Cap d’Antibes in the south of France. “For the future heroes and collaborationists/basking together in the Mediterranean sun,/it is ‘our last summer,’” Morgenthau writes in his poem “A Marvelous Party.” A favorite diversion for both Morgenthau and Kennedy was sitting on the hotel veranda to watch film star Marlene Dietrich, another guest, sunbathing on the rocks.

Taking a break from his tea, Morgenthau sits back in a parlor in his apartment where busts of his father and FDR stare at each other across the room. On the wall behind him hangs a doodle Roosevelt drew for young Morgenthau in 1930. Possessed with a cruel sense of humor — he nicknamed Morgenthau’s dour and portly father “Henry the Morgue”— FDR sketched three figures, of Morgenthau at the ages of 13, 20, and 40, each with a larger belly. “Awful fate,” Roosevelt wrote, “May be avoided by NOT following Pa’s example.”

When he was governor of New York, Roosevelt often would drop by for dinner at the Morgenthau farm in the town of East Fishkill, where the family raised chickens and cows and grew apples. “We would lean over the banister and listen to him,” Morgenthau recalls. “He loved to tell these great stories, and at the end he would always say, ‘Don’t you love it?’” During World War II, Roosevelt once brought Winston Churchill over for mint juleps. Churchill hated them, Morgenthau says.

“Writing poetry for me is a celebration of the evening of a long life — a coda, a strikingly new expression of my inner being that surprises me as much as those who know me.”

Henry Morgenthau III ’39

On March 4, 1933, Morgenthau sat just below the inaugural stand at the U.S. Capitol as Roosevelt proclaimed, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” A little less than nine years later, he was in the packed House gallery, seated on a step next to presidential aide Harry Hopkins, when FDR sought a declaration of war against Japan. In 1940, he danced at his sister Joan’s debutante party in the White House and recalls Eleanor Roosevelt as an unexpectedly graceful dancer.

In later years, Morgenthau became a documentary filmmaker for Boston public television station WGBH, and from 1959–1962 produced a series, Prospects of Mankind, with Mrs. Roosevelt. She once told him of a day she spent in Harlem with Adlai Stevenson ’22 during one of Stevenson’s presidential campaigns. When crowds recognized them at a traffic light and surged around their car, Stevenson recoiled in the back seat. “What am I going to say to these people?” he asked.

“If he didn’t know,” Morgenthau remembers Mrs. Roosevelt saying, “there was nothing I could tell him.”

Morgenthau’s documentaries were groundbreaking. In 1963, he produced The Negro and American Promise, featuring interviews with King, James Baldwin, and Malcolm X. Baldwin’s interview was filmed on May 24, 1963, after an incendiary meeting, which Morgenthau also attended, between civil-rights advocates and Attorney General Robert Kennedy at Kennedy’s Manhattan apartment. Baldwin was still angry at the taping, and it shows. “I realized that we had something that was really hot,” Morgenthau recalls. Indeed, a clip from the interview appears in the new Oscar-nominated documentary about Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro.

Keep asking, and the stories keep coming. When Morgenthau was an undergraduate, his grandfather took him to pay a call on Einstein at his home on Mercer Street. Einstein was interested to learn that Morgenthau was majoring in art history and bored in with penetrating questions. Morgenthau still shudders that he answered inarticulately: “Einstein was warm and courteous, but I sort of felt that he was seeing right through me,” he recalls.

Although he wrote a family history, Mostly Morgenthaus, in 1991, he says he began attending poetry workshops in his mid-’90s in part to establish his own identity within his family’s distinguished line. He showed his work to a few people and was encouraged to go on. In fact, Morgenthau writes for the best reason of all: because he has something to say.

“Writing poetry for me is a celebration of the evening of a long life,” he explains in an introduction to A Sunday in Purgatory, “a coda, a strikingly new expression of my inner being that surprises me as much as those who know me. Now as death kindly waits for me, I am enlivened with thoughts I can’t take with me.”

Morgenthau published his first poem in 2013, but describes the collection as a “fluke.” Uncertain whether his work was good enough, he declined to submit most of it to a publisher. Friends did so without his knowledge, telling him afterward, “We hope you don’t mind that we went behind your back.” Poet David Keplinger likens Morgenthau’s work to the confessionary style of Robert Lowell, an old friend whose influence he acknowledges. Several poems in the collection look back at his privileged youth (“Our Crowd” muses about “the gilded ghetto/ of Manhattan’s Upper West Side” where he grew up), but more are introspective, revelatory, and bluntly self-critical, though sometimes sweetened by humor. “Pack up your troubles/in your old kit bag/and hand them over/to your psychiatrist,” he writes.

Though a bit unsteady on his feet, Morgenthau remains hale for 100. In the collection’s title poem, he assesses the current landscape:

At Ingleside, a faith-based community

for vintage Presbyterians, I am an old Jew.

But that’s another story.

I’m not complaining with so much I want to do,

doing it at my pace, slowly.

Anticipation of death is like looking for a new job.

Like many who have lived so long, Morgenthau admits to a love-hate relationship with the medical profession. “They do a lot of things to keep you going, but the aging process still goes on.” There are days when it surprises even him: “Sometimes I accidentally look in the mirror and I see this rusted, ancient machinery that was built during World War I.”

So, linger. Urge him back for one more reminiscence about a world long gone. Despite his family’s prominence, young Morgenthau was excluded from the Prospect Avenue eating clubs because he was Jewish. “It was an emasculating experience that left me feeling that I was something less than a Princeton man,” he wrote bitterly in his family history.

Decades after he had been snubbed, when his daughter was looking at colleges, Morgenthau took her to Nassau Hall to visit his old friend and classmate Fred Fox ’39, who offered to take them on a campus tour.

“He said, ‘Things haven’t changed a bit,’” Morgenthau recalls. “And I said, ‘Freddy, yes they have, and all for the better!’”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

1 Response

Danielle Saroyan, Armenian Assembly of America

7 Years AgoLoss of a Longtime Friend

The Armenian Assembly of America and Armenian National Institute mourn the loss of a longtime friend of the Armenian people, Henry Morgenthau III, who dedicated himself to honoring the memory of his grandfather, Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, passed away on July 10.

In countless public presentations, in television appearances, and in numerous publications, Henry Morgenthau III recounted his recollections of his grandfather with whom he lived in New York City. He was honored on many occasions by Armenian organizations across the country.

The Armenian National Institute and the Armenian Assembly of America shared the distinction of organizing Mr. Morgenthau's trip to Armenia in 1999 where he was honored by the National Academy of Sciences, the Armenian Genocide Museum, and the City of Yerevan.

Morgenthau was joined by his sons Dr. Henry Ben Morgenthau and Kramer Morgenthau, as well as Armenian Assembly President Carolyn Mugar, longtime personal friend of Henry from the time of his residence in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Mrs. Kitty Dukakis, wife of the former governor of the state of Massachusetts and a board member of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The Morgenthau delegation was received by the president of Armenia, Robert Kocharian, met with several other officials including U.S. Ambassador to Armenia Michael Lemmon, and was the guest of honor at the naming of a Yerevan city school in honor of Ambassador Morgenthau.

"My grandfather frequently told me that his attempts to save Armenian lives at the time of the Genocide and the establishment of the Near East Relief effort were the achievements that meant the most to him," Morgenthau explained on the occasion. Ambassador Morgenthau served as President Woodrow Wilson's emissary to the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

With Henry Morgenthau III's endorsement, in 1996 the Armenian Assembly of America established the Henry Morgenthau Award for Meritorious Public Service which is given out to public officials in recognition of their contributions in defense of human rights. Recipients of the Assembly's Morgenthau Award include the first U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of Armenia Harry Gilmore and U.S. Ambassador John Evans who publicly called for official U.S. recognition of the Armenian Genocide.

A friend also of the Armenian National Institute (ANI), Henry Morgenthau III encouraged the organization with symbolic gifts of $1915 and joined with supporters and Armenian Ambassador to the U.S. Tatoul Markarian in the opening of the ANI Library, to which he contributed his grandfather's library.

Henry Morgenthau III was an author and television producer. His family history, Mostly Morgenthaus, won the 1992 National Jewish Book Council prize for best memoir. He was a fellow at the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics, and Public Policy at the Kennedy School of Government of Harvard University. Morgenthau's shows on Boston's public television station, WGBH, won Peabody, Emmy, UPI, EFLA and Flaherty Film Festival awards. Morgenthau also updated his grandfather's memoir, Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, with a lengthy postscript about the Ambassador's life in the 2003 edition of the book published by Wayne State University Press.

Henry Morgenthau III's brother, Robert Morgenthau, also a vocal advocate for Armenian Genocide recognition, served as District Attorney for New York County in Manhattan. Their father, Henry Morgenthau II, was Secretary of the Treasury under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

"The Armenian people have lost a true friend with Henry's passing. His grandfather Ambassador Henry Morgenthau played a critical role as the first opponent of genocide on the world stage as he defended the Armenian people. With his first-hand familiarity of his grandfather’s legacy, Henry stood with the Armenian people throughout his life, always ready to step up immediately to lend his gravitas in support of all essential issues for Armenians,” stated Armenian Assembly President Carolyn Mugar.

"Despite his advancing age, Henry continued to participate in Armenian Genocide commemorative and advocacy events. He was honored at the community-wide Centennial Genocide Commemoration in Washington, D.C. in 2015, where he walked on stage surrounded by his children and grandchildren. The Morgenthaus are legendary within the Armenian community, who are grateful that this noted family validated their traumatic history as a people by informing the entire world,” she continued.

Carolyn added: “Henry was exemplary in carrying on Ambassador Morgenthau’s commitment to genocide recognition and prevention. We all honor him for his total resolve to relentlessly stand up and speak out against injustices of the past. He used his voice to deepen people’s recognition of the importance of acknowledging the truth in history and thereby using this truth to prevent the recurrence of atrocities.”