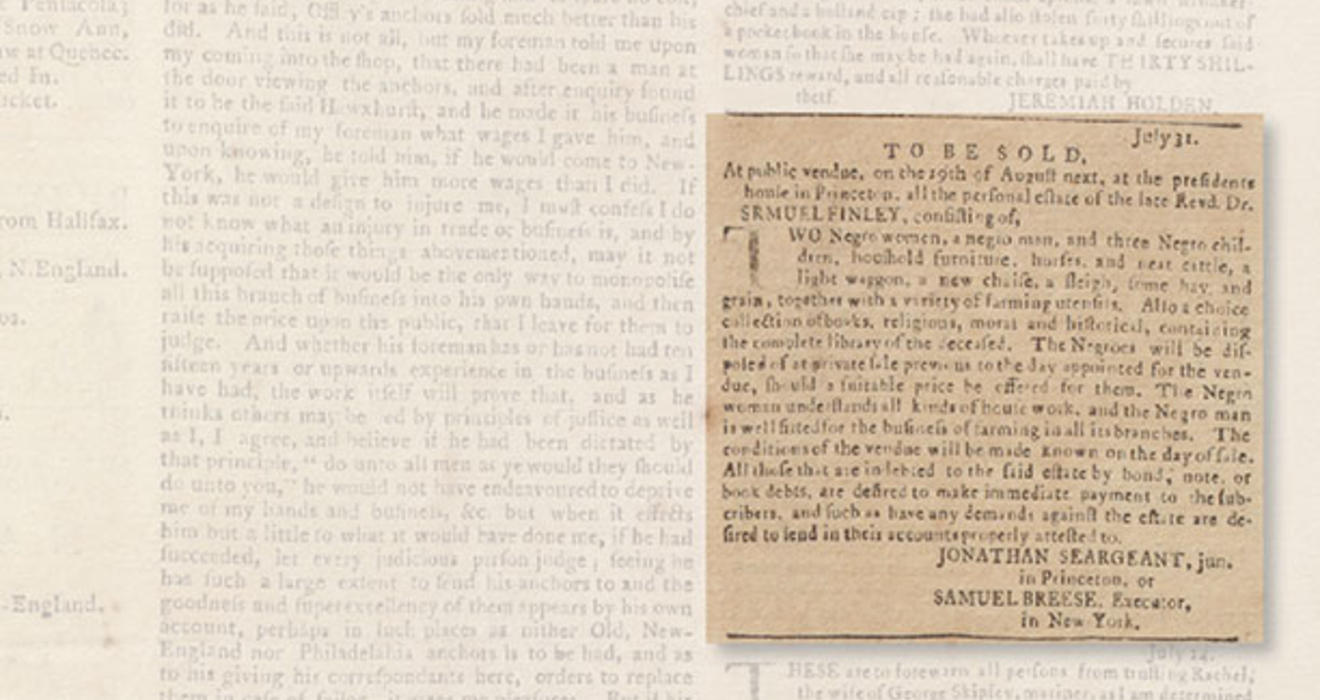

In the spring of 1766, Samuel Finley, fifth president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), planted two sycamore trees in front of the President’s House, a stone’s throw from Nassau Hall, the only other building on campus. Campus lore claims the trees celebrated the repeal of the Stamp Act, and more than two and a half centuries later, those aged trees still frame the old clapboard house, now home to the University’s Alumni Association. Tour guides point to the towering sycamores as living reminders of the College’s devotion to the Revolutionary cause. But the guides do not mention what happened at the house just a few months later, after Finley died in July 1766. His executors announced they would sell his possessions: furniture, cattle, books, and “two Negro women, a Negro man, and three Negro children.” “The Negro woman,” the executors explained, “understands all kinds of house work, and the Negro man is well fitted for the business of farming in all its branches.” The slaves not sold beforehand would be auctioned off Aug. 19 at the President’s House, beside those two young liberty trees.

Princeton University, founded in 1746, exemplifies the central paradox at the heart of American history. From the very start, liberty and slavery were intertwined. The University boasts of being the site of an American victory during the Revolutionary War, and of hosting the Continental Congress in Nassau Hall in 1783. The campus literature fails to note, however, that the first nine presidents of the University, serving until 1854, held slaves at some point in their lives. Early College regulations required prospective students to present themselves to the president for examination before enrolling in the school. For generations of Princeton students, then, the first person they met on campus may have been the enslaved man or woman who answered their knock on the president’s front door. Quite literally, if Nassau Hall provided the storied backdrop of Princeton University, slavery was the face of the school.

More than any other early American college, Princeton was a national institution, drawing its students not just from the surrounding mid-Atlantic region, but also from the South. Presbyterian ministers who trained at Princeton during the Colonial period spread word of the College to the cotton frontier of the early republic. From there, money and boys flowed to the college in New Jersey. Throughout the antebellum period, even as North and South developed increasingly different views about slavery, nearly 40 percent of Princeton’s student body, on average, came from the slave states, providing crucial financial support for the College’s operations. As one mother in Georgia wrote in 1850, “Princeton of all colleges . . . has long had the preference for our dear boys.” Indeed, 63 percent of students in the Class of 1851 were from slave states.

If Princeton embodied the paradoxical connections of liberty and slavery during the Revolutionary era, the institution also exemplified the central tensions of antebellum American life, seeking — in a Northern state only mildly antipathetic toward slavery — to maintain a comfortable environment for slaveholders and their sons. Like the nation itself, Princeton struggled to create a center that would embrace Northerners and Southerners in an oft-uneasy truce. But the tenuous peace at Princeton shattered when the Confederate states seceded in 1861. The Southern boys left for home, knowing they might have to take up arms against their former schoolmates from the North. “Don’t let’s shoot each other,” wrote one to a friend from Pennsylvania. “Though your deadly foe in public life I am in private life your friend.”

Early Princeton students lived within a landscape of slavery. Throughout the Colonial period, slaves constituted 12–15 percent of the population of east New Jersey. After the Revolution, the slave populations of Middlesex and Somerset counties — the two counties that bisected the town of Princeton — increased. In 1794, the College formally prohibited students from bringing their own servants to campus. Nevertheless, students did not have to wander far from Nassau Hall to encounter slaves. Although New Jersey passed in 1804 an act for the gradual abolition of slavery, the state was painfully slow to relinquish the institution. There were 7,557 slaves in New Jersey in 1820 and still 236 slaves remaining in 1850.

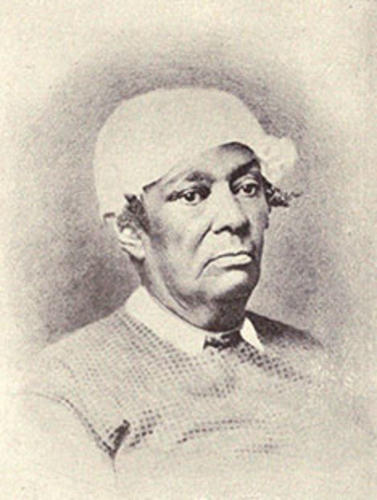

Shortly after moving to Princeton in 1813, Ashbel Green, the College’s eighth president, purchased a 12-year-old named John and an 18-year-old named Phoebe to work as servants in the house. Green wrote in his diary that he would free them each at the age of 25, or 24 “if they served me to my entire satisfaction.” In the meantime, in 1817, he manumitted another of his slaves, Betsey Stockton, who went on to a remarkable career as a missionary in Hawaii and as a teacher in a school for black children in Princeton.

Although no evidence yet suggests that Princeton students brought their own slaves to campus during the Colonial or early national periods, the students regularly encountered enslaved people delivering wood to their rooms, working in town, or laboring in the fields of the privately owned farm adjacent to the campus. They also crossed paths with the slaves who resided at the President’s House. Shortly after moving to Princeton in 1813, Ashbel Green, the College’s eighth president, purchased a 12-year-old named John and an 18-year-old named Phoebe to work as servants in the house. Green wrote in his diary that he would free them each at the age of 25, or 24 “if they served me to my entire satisfaction.” In the meantime, in 1817, he manumitted another of his slaves, Betsey Stockton, who went on to a remarkable career as a missionary in Hawaii and as a teacher in a school for black children in Princeton.

Within this landscape of slavery, Princeton during its first 75 years produced a staggering number of leaders of the American clergy, military, and government, many of whom were “anti-slavery” in the sense that they disapproved of slavery and sought to abolish the institution. The venerated Dr. Benjamin Rush (Class of 1760) and the theologian Jonathan Edwards Jr. (Class of 1765) provided crucial moral leadership during the North’s transition into the “free states.” As Edwards wrote in 1791, “You ... to whom the present blaze of light as to this subject has reached, cannot sin at so cheap a rate as our fathers.” Edwards meant “our fathers” literally. His own father, Jonathan Edwards Sr., had been a slaveholder and Princeton’s third president.

Anti-slavery members of the Princeton community proved particularly active during the so-called “First Emancipation” — the period from the Revolution though the early 19th century when Northern states passed laws for the gradual abolition of slavery, the United States abolished the foreign slave trade, and many slaveholders emancipated their slaves. John Witherspoon provided the intellectual underpinnings for this anti-slavery sentiment at Princeton. Witherspoon emigrated from Scotland in 1768 to become the College’s sixth president. During his 26-year tenure, Princeton became a primary conduit for the diffusion of Scottish moral-philosophical thought, which, in the words of Margaret Abruzzo, emphasized “both human benevolence and sympathy as the foundations of all morality.” Although Witherspoon owned slaves, his teachings gave a generation of students “a language for challenging slavery,” she wrote.

Witherspoon became a political role model for his students. Almost from the start, he criticized the British for encroaching upon American rights, and he later signed the Declaration of Independence and served in the Continental Congress. The Princeton community followed the president’s lead. “No other college in North America,” writes the historian John Murrin, “was so nearly unanimous in support of the Patriot cause. Trustees, faculty, and nearly all alumni and students rallied to the Revolution in a colony fiercely divided by these issues.”

The College’s close identification with the republic came with added responsibility. Witherspoon’s successor, Samuel Stanhope Smith, a member of Princeton’s Class of 1769, taught his students that slavery posed a particularly dire threat to the nation’s spiritual, moral, and political well-being. Like his six predecessors, Smith was — or had been — a slaveholder. Smith nonetheless became an important, if sometimes eccentric, critic of racism and slavery in the early United States. In his 1787 treatise titled an “Essay on the Causes of the Variety of Complexion and Figure in the Human Species,” he posited that racial differences stemmed from nothing more than climate. Later, in 1812, he argued against the ancient Aristotelian notion that civilized nations had a natural right to wage war on barbarians to enslave prisoners, and contended instead that such forms of enslavement constituted “the most unjust title of all to the servile subjection of the human species.”

Smith stopped well short of calling for the immediate abolition of American slavery. “No event,” he exclaimed, “can be more dangerous to a community than the sudden introduction into it of vast multitudes of persons, free in their condition, but without property, and possessing only habits and vices of slavery.” Smith also doubted that the state had the right to compel slaveholders to give up their property. “Neither justice nor humanity,” he wrote, “requires that [a] master, who has become the innocent possessor of that property, should impoverish himself for the benefit of the slave.” As an alternative, Smith floated a few ideas to both encourage voluntary manumission and diminish racial prejudice, including one plan to assign a “district out of the unappropriated lands of the United States, in which each black freedman, or freedwoman, shall receive a certain portion.” He then proposed that “every white man who should marry a black woman, and every white woman who should marry a black man, and reside within the territory, might be entitled to a double portion of the land.” Smith hoped that such interracial marriages would “bring the two races nearer together, and, in a course of time ... obliterate those wide distinctions which are now created by diversity of complexion.” Smith’s views on race and slavery helped shape those of his students.

During Smith’s administration (1795–1812), Princeton produced many graduates who sought a solution to the moral and political problems associated with slavery. Most dismissed the thought of immediate abolition and refused to question the property rights of slaveholders. Nevertheless, they contributed to the pro-reform discourse during the early republic, which in turn set the stage for the rise of the abolitionist movement. For example, in 1816, Smith’s pupil Charles Fenton Mercer (Class of 1797), a slaveholder from Virginia, organized the American movement to colonize free blacks. Mercer did not invent the idea of colonization. But he latched onto it because, like Smith, he worried that emancipated slaves were a drain on public resources and a threat to social order. Mercer echoed Smith’s fear that racism would prevent blacks from assimilating into white society. But while Smith proposed sending blacks to the western frontier, Mercer wanted to send them to Africa.

Mercer enlisted Princeton associates in his endeavor to colonize free blacks. In 1816, he asked Elias B. Caldwell (Class of 1796) to pitch the colonization idea to his brother-in-law, the Rev. Robert Finley (Class of 1787), director of the Princeton Theological Seminary. Finley supported colonization because he believed that slaveholders would be more willing to manumit their slaves if they could then send them far away. With that in mind, Mercer, Caldwell, Finley, and their friend John Randolph — a statesman from Virginia who had briefly attended Princeton — organized the American Society for Colonizing the Free People of Colour of the United States (also known as the American Colonization Society or the ACS).

In effect, Princeton was ground zero for the colonization movement in the United States. The College’s support for the movement drew other Princeton affiliates into the ACS’s effort to colonize free blacks and suppress the African slave trade. Members of the Princeton community helped arrange for Lt. Robert F. Stockton — the scion of Princeton’s most illustrious family — to receive command of a new cruiser that the Navy planned to use in its campaign against the African slave trade. Stockton conducted two tours of the African coast. In addition to suppressing the African slave trade, he personally negotiated on behalf of the ACS the purchase of a 130-mile-long and 40-mile-wide swath of coastline. This land would form the basis of Liberia, the American colony for free blacks.

The real steward of the ACS in New Jersey was a young professor at Princeton named John Maclean Jr., who had graduated from the College in 1816. Maclean took a deep and abiding interest in colonization. As a Northern clergyman, he sought a vehicle to encourage voluntary manumissions, protect society from an influx of newly freed blacks, spread Christianity to Africa, and suppress the African slave trade. But Maclean could also empathize with the reluctance of slaveholders to part with their property. His own father, Princeton’s first chemistry professor, had died in 1814 while in possession of two slaves: a girl named Sal and a boy named Charles. The younger Maclean rose through the ranks to become Princeton’s 10th president in 1854, and throughout his long career sought to promote harmony between the Northern and Southern members of his beloved community. Princeton’s close affiliation with the ACS seemed useful and beneficial. After all, the ACS allowed members of the College community to demonstrate their distaste for slavery, without having to call for its abolition.

In the long run, though, Princeton could not depend on the colonization movement to mediate the conflicting desires of slaveholders and non-slaveholders. During the 1830s, a new generation of abolitionists began to call for the immediate abolition of slavery. Consequently, the colonization movement came under pressure both from those who called for the slaves to be freed, and from the increasingly defensive slaveholders who responded that slavery was actually a positive good for society, rather than a necessary evil. Abolitionists abandoned the ACS and slaveholders became suspicious of the colonization movement, which had tacitly encouraged voluntary manumissions. This polarization sapped the popularity of the ACS, especially in conservative areas like Princeton. The Princeton members of the group were becoming more concerned with abolitionism, which in their view now constituted a greater threat than slavery to the survival of their beloved republic.

In effect, Princeton was ground zero for the colonization movement in the United States. The College’s support for the movement drew other Princeton affiliates into the American Colonization Society’s effort to colonize free blacks and suppress the African slave trade.

On May 9, 1848, Henry Craft sat down to write in his diary. The 25-year-old from Holly Springs, Miss., had come to the College just a few months earlier to study law. He spent some time that day with Daniel Baker, an undergraduate from his hometown. Baker was an aspiring minister who sought a post in New England. But he was anxious about working in a region that held “erroneous opinions & prejudices” regarding slavery. As Craft confided in his diary: “We think almost all slaveholders look upon the institution as an evil, a curse to the country & would gladly blot it out could any feasible plan be devised, but in complete destitution of any such plan think that the evil is a necessary one & should be made as tolerable as possible.”

The increasing sectional conflict during the late antebellum period presented a special dilemma for Princeton. In essence, the College faced the same persistent challenge as the United States itself: the challenge of preserving a community of both slaveholders and non-slaveholders. Some Southern parents worried about exposing their sons to abolitionism. “I am anxious to know all about Princeton before I consent to give you up to the Institution for the formation of your character,” wrote one father in Louisiana to his son in 1856. “If there be ... [a] strong ... abolition feeling there,” he clarified, “I should not desire you to remain in it.” And for many students, from both North and South, the town of Princeton’s sizable free black community challenged their preconceived views. In 1850, Charles C. Jones Jr. of Georgia wrote to his parents that the Negro Sons of Temperance had paraded through town. “It was a strange sight to those of us who were from the slave states,” he noted.

College administrators sought to make their Southern students and slaveholding patrons feel welcome. In 1835, the trustees turned down an offer of $1,000 — a tremendous sum at the time — if the College would admit students “irrespective of color.” Members of the faculty, including the acclaimed theologian Charles Hodge, reassured their Southern students that the Bible sanctioned slavery. Others made no secret of their sympathies for the South. Jones raved about the “truly Southern” chemistry Professor Richard Sears McCulloch (Class of 1836), who would later attempt to build a chemical weapon for the Confederacy.

During the 1830s, ’40s and ’50s, Princeton became increasingly conservative on the subject of slavery. “Whilst I was a student at Nassau Hall,” recalled Alabamian Edward W. Smith, of the Class of 1848, “the political elements that existed there seemed to be entirely conservative, and friendly to the South, and no prejudice to all external appearances, existed in the minds of educated and thoughtful men, in that locality, against our institutions.” Most of the students — Northerners and Southerners alike — avoided discussion of slavery.

Indeed, students focused less on the nation’s peculiar institution than on threats to the status quo. Abolitionists, in particular, raised the students’ ire. In 1835, John Witherspoon Woods, the grandson of President Witherspoon and a member of the Class of 1837, wrote to his mother that 60 of his fellow students nearly lynched an abolitionist. The students “went down to a negro man’s house, where they heard this Abolitionist was holding a meeting ... & taking the fellow by the arms asked him to come along with them.” The abolitionist “refused & told them to stand off, for he had the law on his side & that he would make use of it.” The students retorted that “they had Lynch law which was sufficient for them.” They proceeded to burn the abolitionist’s subscription paper and force him “to run for his life” out of town. Southern students also attempted to impose their own notions of racial superiority on Princeton’s relatively sizable free black community. In 1846, two Southern students — Grenville Peirce and Jerry Taylor — instigated a brawl between Southern and Northern students when they sought retribution against a local black man who had scuffled with them on the street two days earlier. One student recorded in his diary that the black man was ultimately “recaptured —taken out & whipped within an inch of his Life.”

In general, Princeton’s administrators encouraged the notion that abolitionism — and not slavery — posed the most pressing threat to the preservation of peace. In 1850, they invited U.S. Rep. David Kaufman of Texas (Class of 1833) to give a Commencement speech. Kaufman spent much of his hour-and-a-half-long address warning the students to “beware of demagogues in the guise of abolitionists.” He called them “murderers and dis-unionists” who threatened the very existence of American life. “Abolish slavery,” he exclaimed, “and after that the same men would abolish the Bible.”

To keep the peace during a period of mounting sectional tensions over slavery, the Princeton community agreed to disagree. As one proslavery student wrote to an anti-slavery friend in 1860: “Though politically we differ, and each has tried to convince the other that the Constitution does not & does recognize ‘property in men,’ yet in the broad platform of the Union I think we meet.” Some students even boasted of their tolerance for political pluralism. In 1856, Henry Kirke White Muse, a member of the Class of 1859 from Louisiana, informed his father that “politics is the engrossing topic here now, and we have every class: Southern Fire-eaters, ultra-Democrats, Black Republicans, Abolitionists, old line Whigs, etc.” This type of tolerance had its limits, though. “The Black Republicans and abolitionists,” Muse assured, “are very few, and have sense enough to keep their principles to themselves.” Princetonians promoted their community as an example for the broader American public. In one letter to his father, Muse reported that Yale — an institution of “abolition higher lawism” — had allowed the abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher to encourage students to take up arms against slaveholders. “Be sure,” Muse wrote, “that such a thing could never take place at Nassau Hall.” He then added: “Let the Southerners come here. I believe that old Princeton College is THE College, not the college of the South, nor of the North, but the college of the Union.”

But “the college of the Union” could not remain intact without the Union itself. When the Union crumbled in 1861, the College community divided, too. Having endeavored for so long to make Southerners feel at home in Princeton, President Maclean could only advise his students to follow their hearts in picking sides. “Remember Dr. McLean’s advice to us when he spoke of the present agitation in our country,” wrote one member of the Class of 1861 to another. “He bid us [to] decide for ourselves which was right & then go in calmly yet manfully & support our opinion at all cost.” With such advice in mind, Southern students in 1861 began writing after their signatures “CSA” — the new abbreviation for the Confederate States of America.

Princeton’s antebellum distinctiveness as a Northern institution seeking a middle ground on slavery that would placate both Southern and Northern students did not end with the peace at Appomattox. The Civil War monument in the entry foyer of Nassau Hall preserves in marble the school’s middle path, testifying to a distinctive strain of reconciliationist memory that celebrated brotherly sacrifice over politics or moral causes, and denied the very real differences over the institution of slavery that once divided North and South, not to mention the College community.

At Princeton University, which saw some 600 of her sons enlist for military duty during the Civil War, the erasure of history would be complete. The original plans for the University’s Civil War memorial inscribed in 1921–22 called for the students to be grouped by their Union or Confederate affiliation. But University President John Grier Hibben (Class of 1882) rejected this plan: “No, the names shall be placed alphabetically, and no one shall know on which side these young men fought.” The resulting memorial may be the only one in the nation to list the dead from both sides, without indicating the cause for which they died. Well into the 20th century, then, Princeton sought to remain a congenial home for Northerners and Southerners alike, emphasizing the sacrifice that drew its students together rather than the politics that pushed them apart.

In 1924, the University held its Biennial Convention of the Princeton Alumni Association in Atlanta, where the members promoted the University’s longstanding connections with the South. They donated $1,000 toward the construction of the Confederate monument on Stone Mountain, in Georgia, and enjoyed a tour of the site.

Meanwhile, far away from campus, Princeton employed the politics of memory in order to regain its reputation as a welcoming oasis in the North for white Southerners. In 1924, the University held its Biennial Convention of the Princeton Alumni Association in Atlanta, where the members promoted the University’s longstanding connections with the South. They donated $1,000 toward the construction of the Confederate monument on Stone Mountain, in Georgia, and enjoyed a tour of the site. The Trenton Sunday Times noted that Gutzon Borglum, the famous sculptor of the monument, had received an honorary degree from the University. The newspaper also remarked that the Alumni Association’s generous “tribute” to the new Confederate monument could be considered “a memorial to the association of Princeton, from its beginning, with the South, for in antebellum days the sons of Southern families were numerously represented at the old College of New Jersey.” Many of Princeton’s Southern students “gave their lives for the lost cause.”

READ MORE essays at slavery.princeton.edu

Not surprisingly, the representatives from Princeton who attended the meeting also took the opportunity to assure Southerners of the University’s commitment to sectional reconciliation. In a radio address broadcast from Atlanta, President Hibben stated proudly: “It might be of interest to draw attention to the fact that on the memorial tablet in Nassau Hall, our oldest college building, in memory of Princeton men who died in the Civil War, we have placed the names of men of the North and of the South in alphabetical order, indicating that they are all united without distinction in our memory.” In failing, at that particular moment, to grapple as an institution with the larger meanings of the Civil War, Princeton University once again proved itself a mirror to a nation that even now has not fully reckoned with the legacy of slavery.

This essay has been excerpted and adapted from a longer version found at https://slavery.princeton.edu.

Craig B. Hollander, a history professor at the College of New Jersey, was a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton. Princeton history professor Martha A. Sandweiss has directed the Princeton & Slavery Project, begun in 2013.

No responses yet