The public unveiling of the Princeton & Slavery Project’s scholarly research is part of a larger communitywide effort to reflect on the legacy of slavery through the lenses of visual art, film, theater, history, and education. “There are so many ways to learn about the past, and there are so many ways to understand the past,” says Princeton history professor Martha A. Sandweiss, the project’s director.

WEBSITE: The Princeton & Slavery Project’s website, slavery.princeton.edu, was to be officially launched Nov. 6. The site features 90 essays about Princeton’s links to slavery, written by some three dozen students and scholars, as well as maps, charts, portraits, student-created videos, and digitized versions of more than 300 primary-source documents.

The project is culminating in a website, rather than a book, as a sign that the work is ongoing, with new discoveries to be made as researchers draw on the documents the site will make available, Sandweiss says. “I want our website, and this whole project, to make the argument that this isn’t a story that’s dead and over,” she says. “These stories still matter for people around you that you see every day.”

SYMPOSIUM: The Princeton & Slavery Project Symposium, Nov. 17–18, will feature panel discussions about the research and its implications. Researchers and scholars from Princeton and other universities will take part. Nobel Prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison, a retired Princeton humanities professor, will give the Nov. 17 keynote address. Information about the symposium, including ticketing information, is available at slaverysymposium.princeton.edu.

DOCUMENTARY FILM: Journalist and educator Melvin McCray ’74 will premiere a documentary about the impact of slavery on the families of modern-day Princetonians, with screenings Nov. 17 and 19 at the Princeton Garden Theatre. McCray’s film includes interviews with African American and white Princeton alumni whose family histories intersect with the history of slavery, including descendants of a slave, slave-traders, the Confederate general who fired on Fort Sumter, a U.S. Supreme Court justice who decided the infamous Dred Scott case, and the abolitionist Harriet Tubman.

The film wrestles with the question of “historical memory of this institution of slavery — how does it affect us in our current existence?” McCray says. “What role does that play in our contemporary lives?”

PLAYS: McCarter Theatre has commissioned seven 10-minute plays inspired by the work of the Princeton & Slavery Project. Readings will be held at McCarter Nov. 18 and 19.

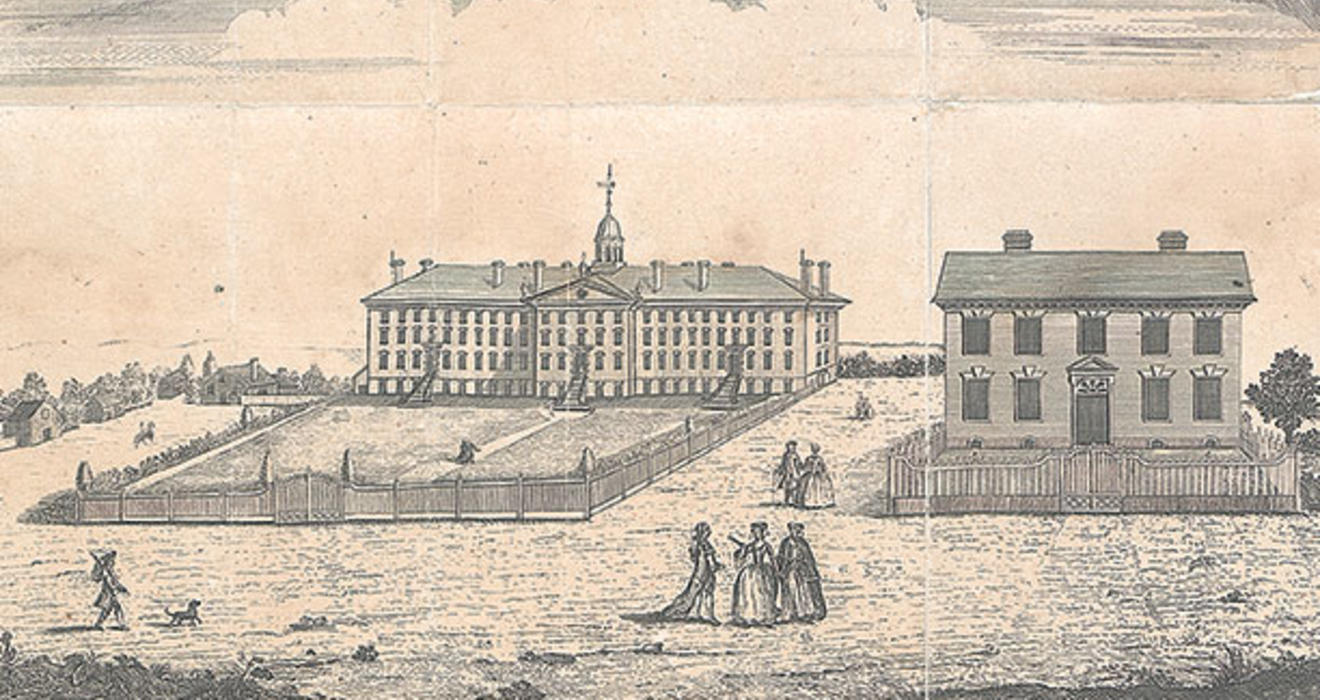

ART EXHIBITION: The Princeton University Art Museum commissioned the contemporary artist Titus Kaphar to create an original work based on the research of the Princeton & Slavery Project. Until December, Kaphar’s piece will be installed outside Maclean House, where a slave auction was advertised to be held in 1766. Through Jan. 14, 2018, the museum will also exhibit an art installation, “Making History Visible: Of American Myths and National Heroes,” that juxtaposes contemporary and historical works in its exploration of how American history is understood and represented.

The exhibition aims to situate Princeton’s links to slavery in “a much broader national discussion about these contested narratives,” says T. Barton Thurber, the museum’s associate director for collections and exhibitions. “This is really the start of a conversation.”

LIBRARY PROGRAMMING: The Princeton Public Library will hold a series of Princeton & Slavery events throughout the fall, including screenings of student films and a discussion of the McCarter plays, facilitated by members of Not In Our Town, Princeton’s anti-racism community coalition. Through Dec. 15, the library will display historical documents about slavery’s connections to the University and the town of Princeton, drawn from the archives of the University and the Historical Society of Princeton.

HIGH SCHOOL CURRICULUM: At Sandweiss’ suggestion, retired Princeton High School history and English supervisor John Anagbo created three lesson plans for high-school teachers based on primary-source documents unearthed by project researchers. One of the lessons was successfully piloted last spring in a ninth-grade American history class at Princeton High School, and Anagbo hopes the school district will eventually incorporate all three into its history curriculum.

Basing lessons on primary sources — including newspaper advertisements, a letter from a Princeton student to his mother, and a journal kept by a white visitor to Princeton — is especially compelling for students, Anagbo says. “Everything speaks for itself. You don’t have to make anything up,” he says. “These are primary documents from which the students themselves can grapple with the issues, where the teachers get out of the way.”

1 Response

Lee Wood

8 Years AgoColumbia U., UC Santa Cruz...

Columbia U., UC Santa Cruz, and several additional colleges/universities have organize and are organizing to divest university-held stock properties in for-profit prisons. The contention is that prisons are slave plantations, and that prisoners are slaves. Student demands have resulted in the divestment of millions of dollars away from for-profit prison corporate stock, and back to universities. Two basic contentions are that all education institutions should be 'free' of SLAVEHOLDING; and that all vestiges and badges of slavery shall be abolished from these universities, including prison slavery.