As part of the Princeton & Slavery Project, students made short videos that illustrate how the legacy of slavery continues to have an impact on Princetonians. The students interviewed alumni and family members and used archived materials to tell multifaceted stories about ancestors’ relationships to the institution of slavery. The videos can be seen at https://slavery.princeton.edu/visualizations/videos. Compiled by James Haynes ’18

Kim Pearson ’78

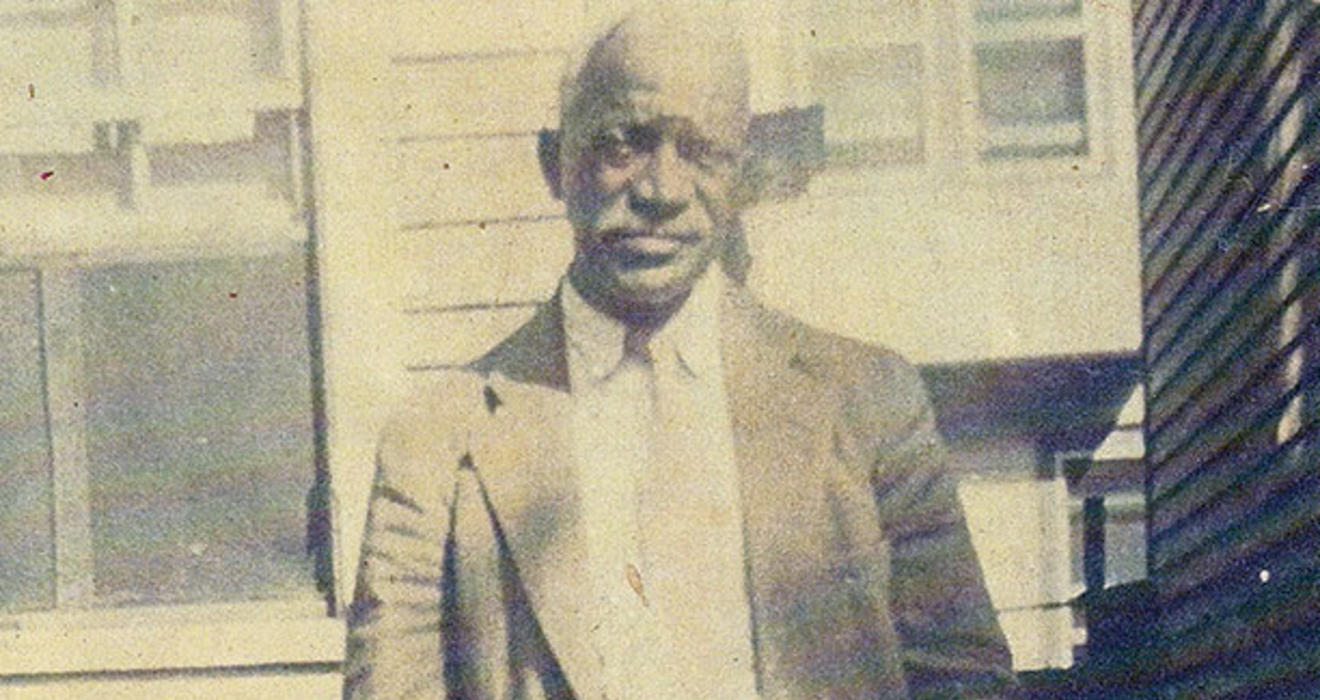

Eli Berman ’20 interviewed Kim Pearson ’78, who describes the pain she felt upon learning about her great-grandfather Jordan Mitchell, above, who had been enslaved as a young child. Pearson found Mitchell’s name in a tax record that listed the slaves belonging to a family in Hancock County, Ga.

Pearson: “The things that are supposed to help you understand yourself — whether it’s the history books, or the primary or secondary documents — you can’t trust those things. You can’t. Because there’s a whole lot of missing information because your family wasn’t important enough for anybody to keep track of them, except as property.”

Destiny Salter ’20

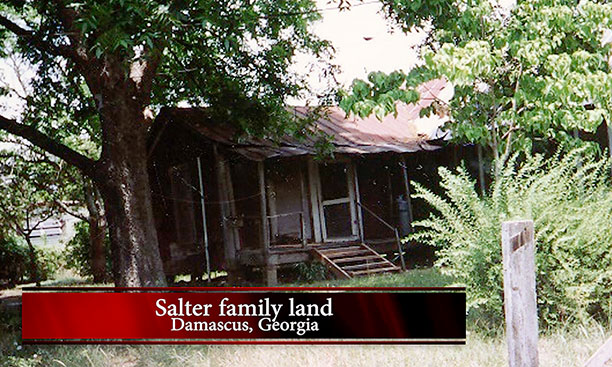

Christo Ritter ’20 interviewed Destiny Salter ’20, whose earliest known ancestor was purchased in 1796 by Henry Salter in Early County, Ga. Destiny Salter’s great-great-great-grandfather Berny was freed after the Civil War, registered to vote, became a sharecropper, and eventually bought land from the white Salter family that remains in her family today.

Salter: “I was not at all surprised to learn about Princeton’s connection to slavery ... this place was not built for people that look like me, and yet I’m here. I made it here, and I’m going to graduate from this institution, and so knowing its connections to slavery makes me feel the progress, in a way.”

John Roderick Heller III ’59

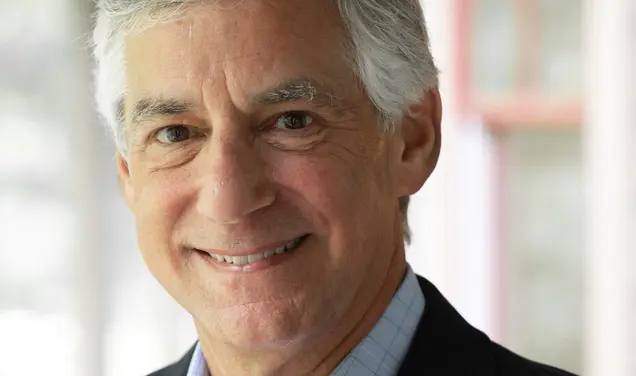

Natalie Nagorski ’20 interviewed her grandfather John Roderick Heller III ’59, a descendant of a slaveholding family.

Heller: “I’m embarrassed and disappointed that my own ancestors were a part of [the institution of slavery]. On the other hand, they happened to settle in the South rather than in the North, so they wound up in an area of slavery over which they presumably had almost no control. I’ve never felt that the sins of the fathers were visited on the descendants.”

Natalie McGowen ’20

Destiny Salter ’20 interviewed Natalie McGowen ’20, an African American student who learned that she is descended from a black slaveholder. McGowen’s great-great-great-grandfather was a property-owning second lieutenant in a mulatto militia.

McGowen: “We always have this image when you’re learning about slavery of a white master and a black slave, so it’s kind of crazy to know that my black ancestor would enslave people of his own race, and it is upsetting.”

1 Response

Sarah Thomas de Benitez *00

8 Years AgoPrinceton Reckons with its Connections to Slavery

On reading the articles about Princeton’s deep associations with slavery, I wondered why white researchers dominated the narrative. Then I landed on a small but illuminating interview (“In Videos, Family Conversations”) with John Roderick Heller III ’59. He (white, corporate CEO) expresses embarrassment and disappointment that his ancestors were slaveholders, but adds: “I’ve never felt that the sins of fathers were visited on the descendants.” I wondered if he felt the same way about wealth and power accumulated by those fathers (on the backs of slaves) that have been so generously “visited” on their descendants? And if he is aware that descendants of slaves have had no such privileges “visited” on them?

This contradiction — moral regret by a University made wealthy by slavery and now planning an expansion that only mildly seeks to increase the “diversity of our students” (President’s Page, Nov. 8) — sits at the heart of this project. Will Princeton simply slough off slavery as a sin of its fathers, bringing in more “poor” students to assuage pangs of embarrassment, while strengthening the (covert) grip of slave-owners’ descendants on wealth and power?

As if to press home the message of respectability about visiting wealth on descendants, a full-page ad on the back cover of this issue (with a photo of three generations of white males) reminds us: “You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely take care of it for the next generation.”

Come on, Princeton. Our institutional message should be much more robust: Slavery produced vast wealth and power for Princeton. Princeton must redress the balance by investing a very significant proportion of that wealth to empower young children, students, academics, and administrators of color — so that wealth and power be equitably visited on descendants of slaves and slave-owners alike.