Decades before divesting from publicly traded fossil fuel companies, Princeton administrators weighed a risky but potentially lucrative opportunity: Should it buy mineral rights in Texas in hopes of striking oil?

Some viewed this as a smart investment following the oil crisis of the 1970s. Princeton, they figured, ought to get onto the supply side of the energy market. But not everyone was as bullish on the idea.

In April 1984, Princeton geosciences professor Kenneth Deffeyes *56 *59 advised the University in a letter to explore putting money into limited partnerships conducting oil exploration, rather than further investing in publicly traded oil and gas companies, but cautioned about potential public backlash, going so far as to compare the move to something an ostentatious entrepreneur might do.

“We all shudder at the thought that Princeton would take its endowment and go out wildcatting: a desperation move worthy of a John DeLorean. Inevitably there would be some dry holes and inevitably there would be plenty of people who could write to PAW that they knew better all along,” he wrote. “On the other hand, it is possible for an individual to take investment risks with the University as the intended beneficiary.”

Three years later, Princeton followed Deffeyes’ advice and formed two limited partnerships: Tiger Energy I and Tiger Energy II. The names changed several months later to PetroTiger I and II and were followed by PetroTiger III in 1989 and PetroTiger IV in 1995.

Based on Princeton’s available tax filings, it made more than $149 million in profits (adjusted for inflation) from the PetroTigers between 2004 and 2022. (PAW consulted with Darryll Jones, a professor of nonprofit tax law at Florida A&M University, in calculating this figure. The University declined a request to fact check it.) The total represents a relatively small gain compared to the $15.6 billion by which the endowment grew during the same period.

Last September, the student activist group Sunrise Princeton released a report that included details about “a fossil fuel company called PetroTiger,” which it described as “an oil and gas enterprise that all evidence suggests Princeton owns.” Vice President of Finance Jim Matteo was asked about PetroTiger by a member of Sunrise Princeton at the September meeting of the Council of the Princeton University Community (CPUC). He said, it is “an energy property that [Princeton has] invested with going back to the 1980s” and the University doesn’t plan to eliminate private investments in fossil fuels.

This prompted PAW to look into how and why the University came to own mineral rights in the Southwest, and the current position of these investments. PAW reviewed thousands of pages of documents — including minutes from meetings of the Board of Trustees and correspondence between administrators — analyzed tax records and court filings, and consulted with tax and oil experts.

PetroTiger I is the only partnership still in business after PetroTiger III was shuttered in December. University spokesperson Jennifer Morrill declined to address the status of PetroTiger I and III or respond to other questions, writing in an email, “We do not comment on individual investments in the endowment.”

Pressure has mounted on Princeton and other universities over the past decade to divest from fossil fuel companies — publicly traded and privately held — as the impact of climate change intensifies. The University announced in 2022 a sweeping plan to dissociate from 90 companies identified as the biggest polluters and divest from public fossil fuel companies.

Nearly 40 years earlier, the debate was also vigorous, albeit different in nature, as Deffeyes articulated in his letter: “It isn’t clear that the University could legitimately encourage this kind of activity. It isn’t clear we have enough interested people to carry it off … . There are lots of questions.”

Princeton was still burning oil to heat the University during the 1970s oil crisis. Richard Spies *72 held various positions with the University from 1971 until 2001, including vice provost and vice president for finance, and recalls the struggle to keep the heat on.

“There were days when we were down to a pretty small reserve there [and] people [were] scrambling around finding oil,” Spies tells PAW. “I was not directly involved in that part of it, but I was involved in ‘how the hell do we budget for this, given that we were going to pay whatever it cost to fill those tanks.’”

An OPEC-led oil embargo in 1973 and the Iranian revolution in 1979 led to price shocks that impacted U.S. oil supply and caused lines and rationing at gas stations. In December 1973, Princeton closed campus for several weeks and delayed final examinations the next month in anticipation of a fuel shortage. In 1971, it cost the University about $1 million to heat the campus, and that figure rose to $3 million by the end of the decade. This meant having to “slash substantially from other programs or face a sizable deficit for 1979-80,” according to The Daily Princetonian at the time.

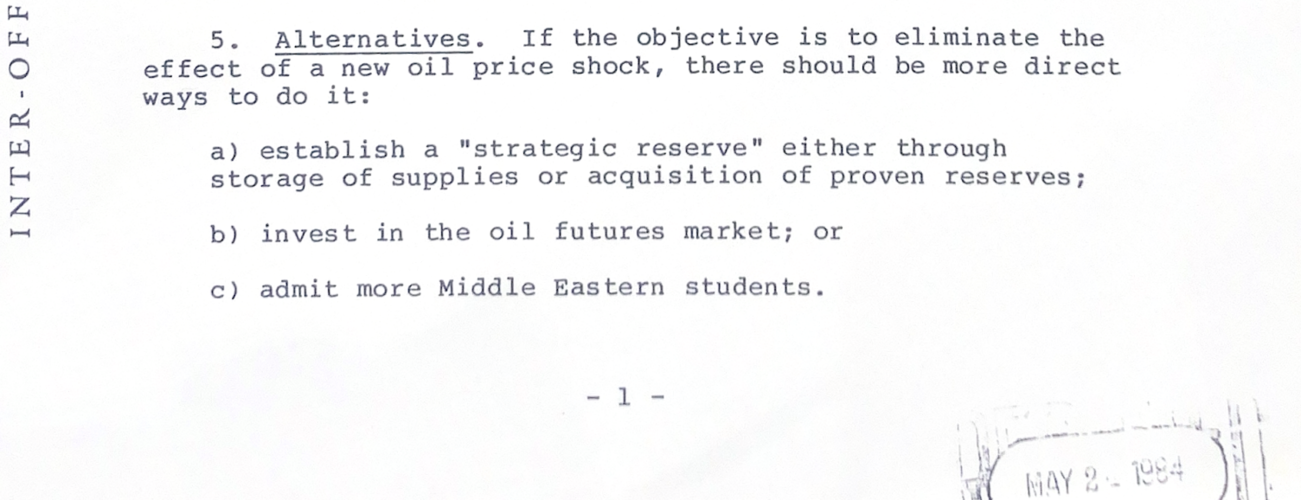

In the early 1980s, there were many opinions on the best way to protect Princeton from fluctuations in the energy market. For example, an April 1984 letter from University tax counsel Donald Meyer to the vice president of development, Van Zandt Williams ’65, suggested a series of moves.

“If the objective is to eliminate the effect of a new oil price shock, there should be more direct ways to do it: a) establish a ‘strategic reserve’ either through storage of supplies or acquisition of proven reserves; b) invest in the oil futures market; or c) admit more Middle Eastern students,” Meyer wrote. Williams says he does not recall this memo, and PAW was unable to contact Meyer through Stanford’s Hoover Institution, where he is listed as counselor to the director.

Although some at the University were uncertain about investing directly in energy assets, Princeton did make a move in that direction in 1983, hiring Houston-based B.P. Huddleston as an oil and gas adviser.

Huddleston was a Texas A&M-educated petroleum engineer and had been a part of Bear Bryant’s famed Junction Boys football team. Shortly after being appointed, Huddleston received a letter from University Finance Vice President and Treasurer Carl Schafer, warning him that making private investments in the energy sector was likely to be met with criticism but that it would be worth it.

“Despite our stress on the people we deal with,” Schafer wrote, “I could imagine a situation in which the property concerned was of sufficient attractiveness that we would not care about the people — so long as we were insulated from them.” (Emphasis in the original.)

E. Philip Cannon ’63 served as a trustee from 1978 through 1982 and lobbied for the University to hire Huddleston. He says Princeton proceeded with its investment strategy, unaware of the impact burning fossil fuels could have on the environment.

“This is back when only Exxon’s inside scientists knew that global warming and the climate crisis were going to become an existential threat,” Cannon says. “The rest of us were still smoking Camel cigarettes and thinking … everything was good, but actually … we knew that cigarettes caused cancer, but we weren’t sure that burning fossil fuels was a bad deal. Even the Rockefeller family were still supportive. So it was not a dark stain on the University.”

Naomi Oreskes, a history of science professor at Harvard, is the co-author of Merchants of Doubt, which details how industry scientists kept the science of global warming under wraps for years. “I think in the 1980s most people close to the issue thought the fossil fuel industry would do the right thing and seek to change its business model, like diversifying into minerals or renewables,” Oreskes tells PAW in an email. “A few did at first, but most did not, and by the 1990s all the [major companies] were pivoting to denial.”

In the next decade, Princeton started to allocate resources into climate education and research. In 1994, the Princeton Environmental Institute (now the High Meadows Environmental Institute) was founded; six years later, the Carbon Mitigation Initiative was established, with funding from BP and Ford Motor Co.; and in 2010, the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment opened. During this time, the University held stock investments in oil and gas companies.

Between March 1983, when Huddleston was hired, and 1986, University officials considered the best way to get into the industry. But pressure was mounting on Princeton to take bolder steps — in part because of the actions of an Ivy rival.

For years, Princeton’s investments had been managed by the Investment Committee of the Board of Trustees. A few men volunteered their time to try to grow the University’s endowment, which in 1985, amounted to $1.5 billion, or $4.5 billion adjusted for inflation. The endowment as of October 2024 was $34.1 billion, according to the University.

“They worked with advisers and sometimes with funds, but primarily they did it themselves,” says Spies. “But the world evolved through the ’70s … and the ’80s — to the point where that was not really sustainable.”

A 1985 article in The New York Times that tracked the highest ranking endowments in the country reported that the University of Texas surpassed Harvard for the top spot, with Princeton third. The Texas endowment had “been built largely from the oil revenue generated from 2.1 million acres of West Texas oil lands it owns,” according to the Times.

The next year, The Wall Street Journal reported that Harken Oil & Gas had “reached an agreement” with a Harvard investment affiliate on “acquiring and managing oil and gas reserves and energy-related companies.”

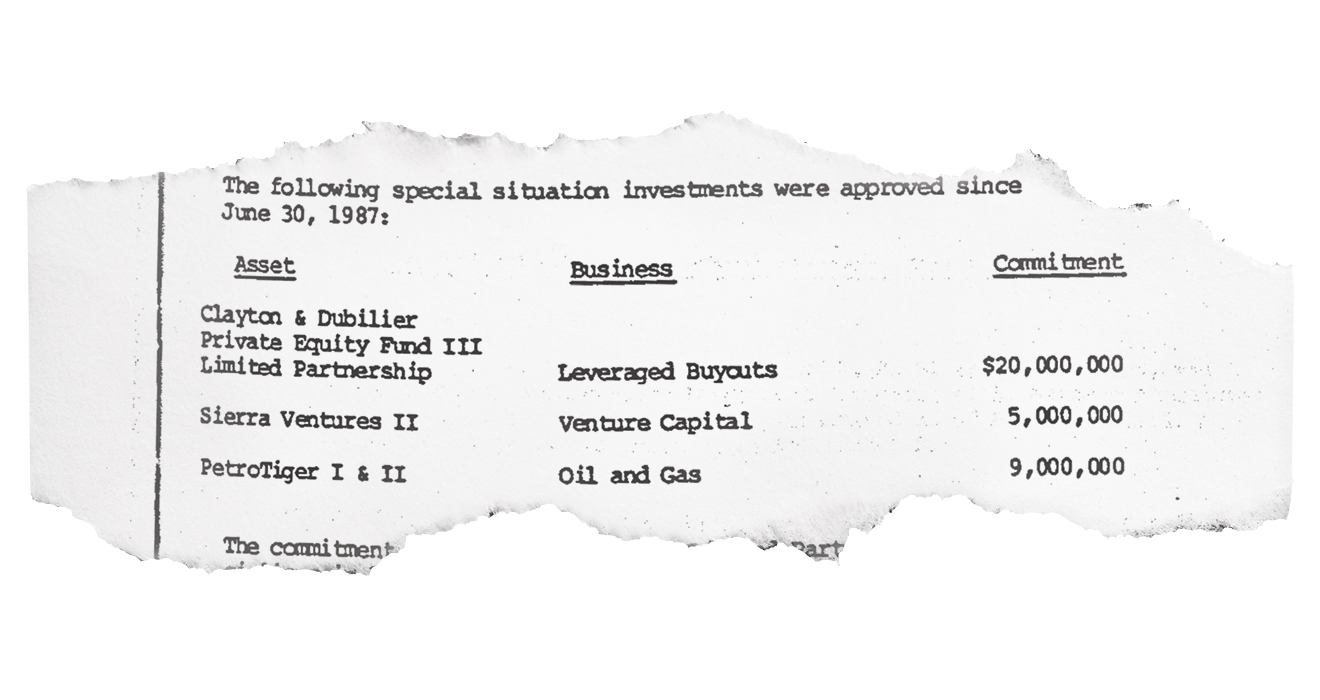

By 1986, Princeton had decided to invest in oil and gas exploration through Huddleston. At the same time, the University was bringing in experts in other investment fields, including venture capital, to diversify Princeton’s portfolio. This culminated in 1987 when the Princeton University Investment Co. (Princo) was formed.

After initially investing in Huddleston’s companies, the University opted to form limited partnerships through which to make these investments: PetroTiger I and PetroTiger II.

PetroTiger I’s investments would be “secured loans and purchases of net profits interests, mineral rights, and other property,” according to minutes from the October 1987 meeting of the Board of Trustees. And, a key factor: “Income from PetroTiger I will not be taxable to the University.”

Since the passage of the Tax Reform Act of 1969, tax-exempt organizations have been permitted to engage in business activities, often through partnerships, that generate income. Some of those activities, including dividends and royalty interests — such as PetroTiger profits — are tax exempt.

PetroTiger II, which was invested in working interests — that is, actual drilling programs — was in a limited partnership with the Forrestal Center Corp., an office and research complex owned by the University.

According to tax filings, profits made by PetroTiger III and PetroTiger IV also weren’t taxable to the University under the 1969 changes to the tax code.

At the same time, Princeton was adding to its portfolio of private oil and gas holdings. In 1987, it brought on Chase Investors Management Corp., through which it made a $10 million investment in Apache Corp. and the Apache Petroleum Co. They expected a 14.4% return.

“The happy circumstance that helped bring us together on this transaction is that Huddleston, who for years has been one of our consultants and who does all of our engineering review work, is also a consultant to Princeton,” wrote Chase Investors president Stephen Cantor in a January 1987 letter to University President Bill Bowen *58.

Princeton’s profits from the PetroTigers in these early years are unclear. Parts of the University archives that contain tax records are under a 30-year seal, making tax records from 1994 through 2000 unavailable. When asked for these records, University spokesperson Michael Hotchkiss told PAW that the Office of Finance and Treasury “searched its on-site and remote storage” and was unable to “locat[e] anything.” (Records from 2001 to 2022 are available online via ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer. PetroTiger does not appear until 2004.)

Years later, PetroTiger I is the only PetroTiger still in business, although it does not engage in oil drilling. According to public records conglomerated and made available by private land surveying companies, in 2024 it held royalty interests in the mineral rights of dozens of properties. Most of these interests are tiny, including 0.0034% of a deposit in Glasscock County, Texas, which was appraised to be worth $680 in 2024, according to lease data from ShaleXP, an online oil and gas property research tool.

“You got to know what you’re doing. I’m probably considered one of maybe a half dozen leading experts in the world on oil and gas law, and I don’t get involved in that [sort of] investment,” says Owen Anderson, a professor at the University of Texas.

Typically, mineral rights under a tract of land are sold and handled separately from the surface land. Over time, mineral rights can become fragmented as people die and leave the rights to family, charitable organizations, or other interests. The owners can lease them to companies that receive royalties on the oil and gas that is extracted.

“These deals — the way that drilling interests, the royalty interests, the leasehold interests, the overriding royalty interests are structured — is dazzlingly complex and very unique to each particular prospect,” says Joe Schremmer, an associate professor of oil and gas law at the University of Oklahoma.

For example, at the time of publication, PAW reviewed records showing that PetroTiger I owns interests in just Texas properties, though older documents, including court records, indicate PetroTiger IV held interests in Oklahoma and Louisiana as well.

Princeton also owns other mineral interests across the country, but many of those were bequeathed.

Public records from the Texas secretary of state show that PetroTiger II, one of the initial companies established by the University, was merged with several other Huddleston-controlled companies in 1996 into Posse Energy. PetroTiger III and PetroTiger IV shared the same registered agent: Posse Resources LLC, which handles tax and governmental regulations.

Founded in 2017, Posse Resources is managed by Peter Currie — B.P. Huddleston’s son-in-law. Currie is also the registered agent for PetroTiger I and Posse Energy (the company with which PetroTiger II merged).

None of the PetroTigers in this story are connected with PetroTiger Ltd., a company unaffiliated with Princeton or Princo that was co-founded by an alumnus and investigated in the 2010s by the Department of Justice before closing.

PetroTigers III and IV were headquartered at the same nondescript corporate office in Houston, Texas, where PetroTiger I and Posse Resources currently share an office with several other gas and oil companies.

PetroTiger I also has links to another company, Muirfield Resources, based in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Multiple court documents show that a company called “Muirfield-PetroTiger 87” is doing business as PetroTiger I. Additionally, at least one mineral lease database shows PetroTiger I shares a P.O. box in Tulsa with Muirfield.

Multiple requests to speak with representatives of Muirfield Resources were unanswered.

B.P. Huddleston died in 2019. Currie did not respond to several voicemails and emails. His son, Mitchell Currie, the vice president of Posse Resources, initially replied to emails seeking comment before stopping.

Should Princeton still be invested in private gas and oil? The University no longer has trouble heating its buildings and is spending “hundreds of millions of dollars” to make the campus net-zero by 2046, according to University President Christopher Eisgruber ’83. However, many argue that completely detaching from fossil fuels will not slow their use around the globe.

“Maybe turn PetroTiger into a sustainable energy investment firm or something,” says Anna Buretta ’27 of Sunrise Princeton. “I don’t see why [these companies exist] just because they started with this a billion years ago when they didn’t know how bad it was.” Buretta wonders why Princeton continues to invest in fossil fuel extraction if they are now aware of the environmental impacts.

Spies, now retired, says the idea that Princeton can “just wipe our hands” of fossil fuels “doesn’t sound good.”

“To me, it doesn’t feel good because, in fact, it’s … pretending that the University really has no connections to fossil fuels, when, in fact, you do,” Spies says. “We’re a part of the world, and we should take some responsibility for that as well as we get benefits from that. So you can’t, on a particular issue, say, ‘Well, that’s not ours.’”

“These deals — the way that drilling interests, the royalty interests, the leasehold interests, the overriding royalty interests are structured — is dazzlingly complex and very unique to each particular prospect.”

— Joe Schremmer, associate professor, University of Oklahoma

Buretta acknowledges that when the University first got into the energy business, the stakes weren’t the same. “But now there is so much research showing that fossil fuel companies are the main cause of climate change, and I don’t see why Princeton can’t change.”

It’s unclear how Princeton plans to handle PetroTiger I — the only remaining PetroTiger — going forward, as the University and Princo do not discuss individual endowment investments.

However, administrators have consistently argued that the investments the University makes in climate research, such as through the Andlinger Center and the Carbon Mitigation Initiative, as well as its plans for a carbon-neutral campus, outweigh whatever financial interests they hold.

In 2022, Eisgruber wrote in the dissociation announcement that “Princeton will have the most significant impact on the climate crisis through the scholarship we generate and the people we educate.”

Lynne Archibald ’87, an organizer for Divest Princeton, a coalition of alumni, students, and faculty formed in 2019 that has called on Princeton to divest from all fossil fuel holdings, says Princeton has already begun to see the effects of climate change, being impacted by wildfire smoke, extreme heat, drought conditions, and hurricanes.

“These things are going to increase, and [it] is a terrible idea that alumni will only begin to pay attention to when Princeton’s physical campus is threatened. But that’s coming,” says Archibald. “What we would like to see is people to be concerned about Princeton as a physical place, as a place that should be a leader in the climate crisis.”

Hope Perry ’24 is PAW’s reporting fellow.

2 Responses

Stephen R. Dartt ’72

9 Months AgoSpeculative Climate Warnings

I feel obligated to point out (once again) the unsupported bias that PAW continues to show in its Inbox. In your May 2025 issue I read “Climate Warnings,” which is prominently displayed over part of two columns. This letter, as with other climate warning letters, contains no proof (or even strong evidence) that human activity is causing global climate change, yet it appears to be arguing that that is the case. In fact, the three bullet items that are emphasized in the letter use the phrases “could act like the glass in a greenhouse,” “could be catastrophic,” and “predict a global surface warning” instead of the phrases “do act like the glass in a greenhouse,” “are catastrophic,” and “show actual global surface warming” or something similar. All three of these claims are speculative, not evidential.

Mitch Golden ’81

11 Months AgoClimate Change Info Available by the Late 1970s

For the most part, the article about Princeton’s investments in petroleum (“Princeton’s Slow Burn,” March issue) speaks for itself. Unfortunately, the article leaves ambiguous what was known about climate change and when. In 1978-82 it was very far from true that “only Exxon inside scientists” knew about the dangers of CO2 emissions, as former trustee E. Philip Cannon ’63 claims. Leaving aside decades of scientific papers, even public policy documents had been warning for years:

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson’s Science Advisory Committee warned “an increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide could act, much like the glass in a greenhouse, to raise the temperature of the lower air.”

In a 1977 memorandum, Frank Press, President Jimmy Carter’s chief science adviser, warned that “the potential effect on the environment of a climatic fluctuation of such rapidity could be catastrophic.”

A 1979 National Research Council report concluded “the more realistic of the modeling efforts predict a global surface warming of between 2° C and 3.5° C.”

Exxon’s scientists never knew anything qualitatively different from the rest of the scientific community — and many other companies knew the same. Thanks to the efforts of Exxon and others, much of the public might not have understood the path we were on, but anyone at Princeton who wanted to understand the climate could have walked over to the geosciences department and gotten a full explanation.