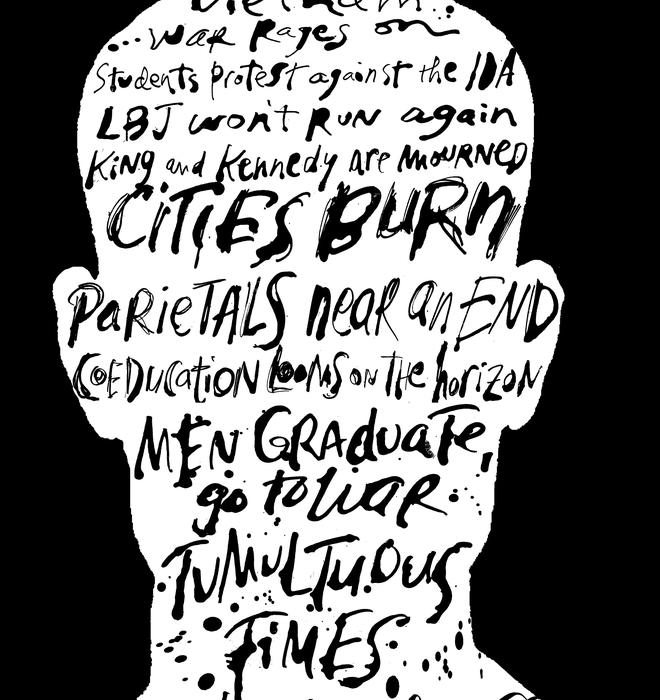

The rites of Princeton University’s 221st Commencement played out on the sun-swept lawn of Nassau Hall on June 11, 1968, after a semester of national torment and heartbreak.

Former Supreme Court Justice Arthur J. Goldberg received an honorary degree, along with the poet Marianne Moore; John Doar ’44, the Justice Department’s point man in civil-rights battles across the South; and other luminaries. In the folding seats stretching back to FitzRandolph Gate sat the 756 graduates in the Class of 1968 and 514 master’s- and doctoral-degree recipients, and their families. The last months of their Princeton experience had unfolded against a blur of tragedies and stunning events: the Tet offensive, the abrupt end of draft deferments for graduate school, incumbent Lyndon B. Johnson’s withdrawal from the presidential race, the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the ensuing riots in Trenton and 100 other cities, the strike that shut down Columbia University, and, finally, the bullets that felled Sen. Robert F. Kennedy moments after he celebrated his triumph in California’s Democratic primary.

There had been talk of canceling the P-Rade on Saturday, the day of the Kennedy funeral. Instead, it was curtailed, confined to campus instead of winding through town. “It felt like nothing was ever going to be the same, here or anywhere else,” remembers Timothy McFeeley ’68, who would spend that summer touring Europe with the Princeton and Smith glee clubs. The group had stops in Paris, where students were rioting on Bastille Day, and Prague, enjoying a last month of liberty under Alexander Dub¹cek before Warsaw Pact tanks crushed the “Prague Spring.”

It had been a year when Princeton, too, faced rising protests — not only over the war and the campus outpost of the Institute for Defense Analyses, but over dormitory rules and divestiture from businesses dealing with apartheid South Africa. Coeducation was on the horizon (Professor Gardner Patterson and his committee were at work), but still a year away. Sociologist Suzanne Keller that spring became the first woman appointed to a tenure-track faculty position, but Suzanne Gossett *68, a student in the early days of coeducation in the Graduate School and now a professor of English at Loyola University Chicago, says some professors seemed astonished that she actually sought a job after completing her doctorate.

“I always describe 1968 as the worst year that ever was — one damn thing after another,” says William H. Earle ’69, a Baltimore writer and editor. “I remember a lot of it as terrifying.” Earle unexpectedly was thrust into the center of controversy over the dorm restrictions known as parietals at the end of exam week in January 1968. His girlfriend was visiting from Bryn Mawr. A proctor — one of the University’s seven-member, plainclothes security force — knocked on Earle’s Cuyler Hall door at 10:30 p.m. to deliver a routine notice from the English department. “Come in,” Earle called out, only to be peremptorily told by the proctor that his visitor must leave, since it was after 7 p.m. on a weeknight (the hours extended to midnight on weekends). But his girlfriend had no other place to spend the night, and Earle stoutly refused to comply. “I said a lot of things. I was pretty annoyed, but I did take her out eventually,” he recalls. He found room for her that night at a married student’s place in town. Earle was hauled before a disciplinary committee and, for refusing to agree to obey the rules in the future, ordered to withdraw for a year.

The case quickly became a cause célèbre. The Prince originally planned to run an account playing the incident for laughs, but “it was anything but comic to me. We managed to get it rewritten as a serious news story,” says Earle. Student leaders intervened on his behalf, and a compromise was struck: Earle’s punishment was changed to probation and the dean of students let it be known that while parietals would stay on the books, there were no plans to enforce them, according to Marc E. Lackritz ’68, the president of the Undergraduate Assembly.

Writing in a 1968 Bric-a-Brac essay titled “Going Forward” instead of “Going Back,” David S. Gould ’68 described that senior year: “Miraculously, the clouds started to part, and for the first time in 67 years, the 20th century threatened to break through.” Gould — lawyer, speechwriter, and wag — was a “ferocious” supporter of the Commit-tee for Coeducation, a student group. “The absence of women was the greatest drawback to my Princeton education,” he wrote in the class’s 35th-reunion book. Noting that the class was among the first with more public- than private-school graduates, Gould opined, “Our class must have driven the administration crazy. Even though the Princeton Class of ’68 was still far behind other schools in social activism, we were doing things that were unheard of in the lore of Princeton University.”

Kenneth Michaelchuck ’68 skipped graduation for his honeymoon. He and his high school sweetheart, Kathleen, had wed back home in Paulsboro, N.J., on Saturday, June 8; they’d set the date without checking on graduation. Michael-chuck, a construction worker’s son, already had enlisted in the Army and had a job waiting with Procter & Gamble. “That whole spring, the country was really in turmoil, plus you’d had the riots, the cities on fire,” says Michaelchuck, who became a Miller Brewing executive and later vice president and CIO of Philip Morris Co. “When I enlisted in May I had to go to Newark. I got off the train to go to the federal building, and the city had been burned out. I kept thinking to myself, ‘Vietnam can’t be any worse than this.’ It looked like a war zone.” The Army sent Michaelchuck to Alaska instead of Vietnam.

Not everyone remembers the summer of ’68 as a season of torment. “I didn’t feel it as a hectic spring,” says Roger S. Cooper ’68, one of 78 graduating seniors commissioned into the Army, Air Force, Navy, or Marines. “Except for getting my thesis done, I didn’t feel any pressure. It was very pleasant. ... I was unaffected by the turmoil going on in the rest of the world, in all honesty.” Cooper, a statistics major, made the Navy his career. He captained a guided-missile frigate and became an arms-control negotiator. Now a defense analyst, he says, “People always ask me, ‘What about SDS [Students for a Democratic Society] on campus and things like that?’ SDS? It was like the Senate used to be, where the Republicans and the Democrats disagreed, but they talked to each other. The same thing with ROTC and SDS. I had close friends who didn’t believe in what I was doing, but they didn’t get violent or anything. I didn’t experience that at Princeton, ever.” SDS even challenged ROTC to a game of touch football over Yale weekend. The radicals won.

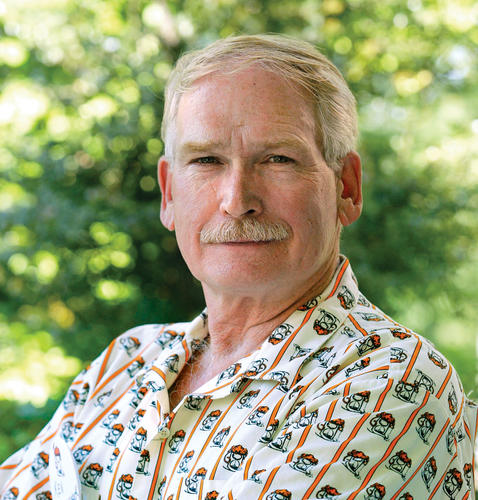

Future Marine officer Eric L. Chase ’68 remembers sitting on the edge of his seat at Commencement, ready to get on with life and “with a certain eagerness to go to war.” His father, Harold W. “Hal” Chase ’43 *54, back for his own 25th reunion, had sworn in Eric as a Marine officer the day before. The elder Chase, a political scientist and former Princeton professor, was a colonel and later a major general in the Marine Reserves who had returned to active duty and led an amphibious assault battalion in Vietnam, his third war. Eric Chase, a wrestler at Andover and Princeton, would be wounded in Vietnam leading a combat patrol in Que Sanh in 1970. In June 2006, he swore in his own son, Eric ’06, and two classmates as Marine officers; the son is now serving in Iraq. The father does his battles these days in the courtroom as a commercial litigator. It troubles him that the military is no longer part of life for most Princetonians. “One of the things I liked about the Class of ’68 [was that] there was a lot of protesting going on, a lot of disagreement, and it was fine,” says Chase. “That’s not true anymore. You get a lot of disparagement of views that don’t conform to what most people want to hear.”

Air Force ROTC product Hervey Stockman Jr. ’68, known as Peter, also received his diploma on Commencement morning, uncertain whether his father, Air Force fighter pilot Hervey S. Stockman ’44, had survived the crash of his plane over North Vietnam in June 1967. Eighteen more months would pass before Peter and his mother got confirmation that the elder Stockman was a POW; he spent nearly six years in Hanoi prisons and emerged to write a paper for the Air Force War College on how and why so many U.S. aviators survived that ordeal as well as they did. The son says his father had encouraged him to join ROTC at Princeton “because he was concerned about Vietnam.” He did so, and the Air Force allowed the young officer to pursue his Ph.D. in physics afterward; Stockman became a top NASA scientist and deputy director of the Hubble Space Telescope program, and is now head of the James Webb Space Telescope Mission Office. Asked if the vocal anti-war students on campus that spring bothered him, Stockman says, “Maybe a little bit, but on the other hand I could see why they were upset with the war. ... It’s hard to be for a war in which the government you’re supporting clearly is not very strong.”

Benjamin R. Foster ’68 returned to his dorm for one last check of the mail after the graduation ceremony and found a draft board notice reclassifying him 1-A, subject to being drafted immediately. He wound up as an ammunition specialist in Vietnam before returning to graduate school at Yale. “I felt I’d lost two years of my life, but there it was, and I was highly motivated. I could hardly wait to open a book, and I couldn’t bear to put a book down. Military service was a colossal motivator,” says Foster, a Yale professor of Assyriology and Babylonian literature. He laments that Americans now are dying in another “pointless and stupid war.”

The draft and Vietnam led architecture major William Brundige ’68 to detour into teaching. His draft board renewed his deferment when he signed up to teach at an inner-city Los Angeles junior high. Later, after earning a master’s degree in architecture at the University of Southern California, he found that teaching, not architecture, had become his passion. He is still in the Los Angeles public schools, teaching six sections a day of technical arts, 41 students to the class, at Fairfax High School. He teaches summer school as well. He stuck with teaching, he says, “because of the happiness that it’s brought me all these years.”

Robert B. Schoene ’68 regards 1968 as “one of the most important and pivotal years of the 20th century in our country’s history.” Schoene was the starting quarterback on the football team his senior year, but a knee injury in the Cornell game ended his season prematurely. “I was sort of devastated for 36 hours, but all of a sudden it came over me that much more important things were going on,” says Schoene, a physician, mountaineer, and expert on high-altitude sickness.

“I think about 1968 every day. I really do,” says the University of California, San Diego, medical school professor, who keeps a picture in his office of the clenched-fist salute by sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the Olympics in Mexico City that October. The 1967 riots in Watts, Newark, and Detroit had made a deep impression on him; the assassinations of King and Kennedy left him emotionally drained. His face is angry in all the pictures his family took that day at graduation. Schoene recalls that one day that spring, when SDS was staging a protest, some football teammates came by his room “and said, ‘We have to go defend Nassau Hall.’ By that time I had rethought things. These were my friends, but I said, ‘You know, I can’t do that. I think SDS is correct.’”

When students organized a weekend anti-war fast and study-in in February at the Woodrow Wilson School, Nassau Hall touted the event with a press release noting that participants included class officers “and the captains of the football and lacrosse teams.” Stephen B. Richer ’68 gained national attention for efforts to get Robert Kennedy’s name added to the Democratic presidential primary ballot in New Jersey. Kennedy jumped into the race a few days after Sen. Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, the peace candidate, nearly upset President Johnson in the March 12 New Hampshire primary. Many students were still home on spring break on March 31, when LBJ addressed the nation about a halt to the bombing of North Vietnam and his surprise announcement at the very end that he would not seek re-election. Lackritz, a future Rhodes Scholar who was completing his senior thesis on Cleveland’s 1966 riots, recalls “whooping, hollering, and celebrating” in the Wilson School, which LBJ had dedicated two years earlier. But as John V.H. Dippel ’68 wrote in PAW’s On The Campus column, “absolute euphoria” quickly turned to “complete bewilderment” four nights later with the shocking news from Memphis.

Apart from being all-male, Princeton in 1968 was overwhelmingly white. There were three dozen African-American undergraduates on campus that spring, and most marched to Walter B. Lowrie House, the president’s residence, an hour before midnight on Sunday, April 7, to remonstrate when President Robert F. Goheen ’40 *48 decided not to cancel classes on Tuesday, the day of Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral. Goheen had assured students, faculty, and staff they could spend as much time as they wished that day commemorating King’s life, but said official activities would pause only for a moment of silence at noon. Going ahead with the pursuit of education “may well be the best tribute we can pay this great man,” the president reasoned.

The year-old Association of Black Collegians (ABC), in a pronouncement printed in the Prince, said its members were “numbed and shocked by the brutal slaying of the world’s apostle of non-violence.” Whatever Nassau Hall did, ABC members would “withdraw totally from ‘the Princeton Experience’ [Tuesday]. No black student will attend classes! No black student will work on any job! It will be a day of quiet meditation and reflection.”

Goheen and his family had moved just 10 days earlier from Prospect House into the new official residence on Stockton Street. The ABC members, led by seniors Deane Buchanan and Paul Williams, clustered on the porch and rang the doorbell. Goheen emerged and heard them out for the next half-hour. Finally, the president told the students they had convinced him: Classes would be canceled. “I didn’t realize that the cancellation of classes was that significant a symbol. I didn’t realize the intense concern the ABC felt,” the Prince quoted him as telling the students on his porch.

Buchanan, now a municipal judge in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, says it was important for the University to acknowledge “the loss of what this man meant to our country, not just the black people, but the importance of this man to our country.” But he adds, “It was very courageous of Dr. Goheen to stand there and speak with us students not knowing what our intentions were, other than to have an unscheduled discussion with him.” In Alexander Hall on the day of the King funeral — at one of an emotional series of ABC-organized events — Paul Williams told an overflow audience, “Violence is not what we’re advocating. If we wanted violence, we wouldn’t be here today.”

A week later, the admission office announced that the number of black students admitted in the next entering class had more than tripled. At Commencement, there would be a surprise addition to the awards printed in the formal program: ABC leaders Buchanan and Williams were asked to step forward to receive the first Frederick Douglass Service Award. “It was a tremendous surprise,” says Buchanan. “I was just amazed. The theme of ‘Princeton in the nation’s service’ has always been a statement of significance for the University. ... This was the Univer-sity recognizing the importance of generating student leadership among blacks.” His co-winner, now Paul X. Carryon ’68, became a cardiologist in Chicago.

The semester hurtled on. Later in April, Princeton’s trustees voted to liberalize parietals instead of to eliminate them. Women would be allowed in dorms until 2 a.m. on Fridays and Saturdays and until midnight the rest of the week, and undergraduates now could live off campus. The gesture only antagonized those it was meant to placate. A “travesty ... senseless and disgraceful,” howled the editors of the Prince.

That year’s protests — which included the arrest of 30 students (14 seniors among them) for blockading IDA’s doors in October 1967 — came to a head with a march and rally outside Nassau Hall on Friday, May 2, 1968, that drew more than 1,000 people. Goheen, after listening to all the demands, gave his own speech promising faculty and students a say in University governance. Parietals were scuttled. The protests, for now, were over. Then the RFK assassination cast its pall on the end-of-year rituals.

James A. Winn ’68 recalled in his class’s 25th-reunion yearbook how unreal it seemed, with the draft hanging over so many heads. “Here we were, reveling toward graduation in one of Princeton’s most achingly beautiful springs, performing the rites of Houseparties and Class Day without ever being able to forget the uncertainty that lay beyond.” Winn enlisted, but later won a discharge as a conscientious objector. He became a professor of English literature.

The class valedictorian, Robert L. Jaffe, a 22-year-old physics major from Stamford, Conn., had misgivings when University Secretary Jeremiah Finch notified him that he had been chosen for the honor. Jaffe thought valedictories were customarily given over to effusive words. “I wasn’t in that mood,” he says. He was upset about the war, about bicker and the pace of change at Princeton, and by the violent turn of events at Columbia. Jaffe used the platform to offer an impassioned defense of student activism, coupled with a warning against the “disruption and destruction” exhibited on Morningside Heights. “Over all our years here has hung the specter of an unpopular and seemingly endless war, one which many of us also feel to be unjust. Alongside this conflict has risen another, sprung from the struggle of the blacks of our country to obtain equality and to find dignity. We have watched and found that we cannot wait for others to confront these issues,” the valedictorian said. To solve America’s problems, “we must go beyond institutional rearrangement and reform; we must ... effect profound changes inside the hearts and minds of the American people. We cannot alienate ourselves in our frustration and our discontent from the majority of Americans with whom we must communicate if we are to improve the country.” Jaffe later took part in war protests as a graduate student at Stanford and got involved in a forerunner of the Union of Concerned Scientists. He went on to make important discoveries on the physics of quarks at MIT, where he holds an endowed chair and has received numerous teaching awards.

Salutatorian Donald McCabe ’68 delivered the customary Latin address, with classmates following a script telling them when to cheer, hiss, or applaud. Still, McCabe ended on a somber note. “So we salute you, alma mater, as many of us prepare to leave and go to war, and perhaps to die.”

Fifty weeks later, Marine Lt. Will Pyle ’68 was killed trying to reach wounded members of his platoon in Vietnam. Pyle was an architecture major who had undergone Marine Corps officer training at Princeton. He and fellow Tower Club member William Van Stone Jr. ’68, who perished in the crash of his Navy jet in Washington state in 1970, are among the two dozen Princetonians killed during the Vietnam era whose names are engraved on the memorial wall in the atrium of Nassau Hall. The Class of 1966 lost five members, the Class of 1961 three, and the Classes of 1962 and 1965 two each. Eight undergraduate classes have a single name on that section of the wall (1931, 1943, 1954, 1955, 1956, 1964, 1967 and 1969). Two Graduate School alumni (1959 and 1962) gave their lives during the conflict in Southeast Asia.

Nineteen-sixty eight was the worst year for U.S. casualties in Vietnam. More than 16,000 of the 58,000 names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., honor those who fell that year. Republican Richard M. Nixon would win the presidency in the fall, promising “peace with honor” and an end to the unpopular draft. The first draft lottery, in December 1969, would reduce some of the uncertainties that many in the Class of 1968 faced; the switch to an all-volunteer force in 1973 eliminated them entirely.

That semester also was the final one at Princeton for Alpheus Thomas Mason, the constitutional scholar and McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence, forced to take emeritus status at age 68 after 43 years on the faculty. Mason was neither ready nor rusty; he spent the next dozen years teaching at Harvard, Dartmouth, the University of Virginia, and other institutions and lived to 90.

For Timothy McFeeley ’68, it was Professor Mason who helped him make sense of that tormented spring. McFeeley, executive director of the Human Rights Campaign Fund, the nation’s largest gay and lesbian political organization, from 1989 to 1995, says he feels Mason’s influence to this day.

What he learned from the legal scholar, McFeeley says, was that “despite everything that was happening politically, culturally, and socially, there was this institution and this incredible document called the Constitution of the United States that would provide an anchor for the Republic, and for people in it.”

Christopher Connell ’71 is a freelance writer in Alexandria, Va., and former assistant chief of the Washington bureau of The Associated Press.

![1968_Chase.jpg “One of the things I liked about the Class of ’68 [was that] there was a lot of protesting going on, a lot of disagreement, and it was fine,” says Eric L. Chase ’68.](/sites/default/files/styles/cke_media_resize_medium_height_500/public/images/content/1968_Chase.jpg?itok=SeF3nGM_)

1 Response

Bill Swan ’68

10 Years AgoRemembering 1968