Stanley Jordan ’81

When Jordan, a guitarist, songwriter, and four-time Grammy nominee, was in his mid-20s, he dazzled veteran musicians with his novel fast-tap method of playing, adapted from his classical piano studies as a child. But by the mid-’90s, after a half-dozen albums and, he says, too many attempts by the music industry to control and limit him, he dropped out for a time, studied music therapy, and rediscovered the fun of “pure rocking out.” With a mix of Béla Bartók and Katy Perry, samba, blues, and jazz, Jordan’s Friends album, released in September 2011, belts out that he will not be labeled.

“In the beginning, people were saying, ‘Oh, you can’t have a career where you play different kinds of music,’ but I pushed back and would mix the rock and the funk into my jazz, and took heat for that. Then some of the old fuddy-duddies from the jazz world were complaining because I changed my look. Now I’ve taken it to even another level because I’m sitting in with these rock bands — Dave Matthews, Umphrey’s McGee, The String Cheese Incident, Phil Lesh.

“It’s this whole jam-band scene where they were doing what I was — rather than keep the music in one vein, they’re open to changing things around. They had room to open up the song and just improvise, and I could take my solos on it. They didn’t have this idea that we’re only doing one kind of music. They just said, ‘C’mon! Play!’

“The real turning point was on this past New Year’s Eve [2011]. I was in Hollywood, went online, and saw that [guitarist] Tim Reynolds was playing right around the corner. I ran over there and ended up ringing in the New Year with his band. I felt like the whole rock thing was sort of a guilty pleasure that you weren’t allowed to do if you were a jazz musician. And now, here I was just going crazy, just pure rocking out, you know? The openness in the rock world was something I had been missing.

“I mean, jazz is my favorite, there’s just no question about that — jazz is my core. But I’ve played songs like ‘Stairway to Heaven,’ I played Beatles, Stevie Wonder, Bach, Mozart. I mean, any music that I like, I’ll play it. There’s so much pressure to strip music down so it can be easily packaged and marketed. But [Princeton professor and composer] Milton Babbitt [*92] had a quote that really sums it up for me: ‘Make music all that it can be, rather than as little as one can get away with.’ That’s what told me all along I was going in the right direction. So one of the songs on the ‘Friends’ album is called ‘One for Milton.’”

Amy Madden ’75

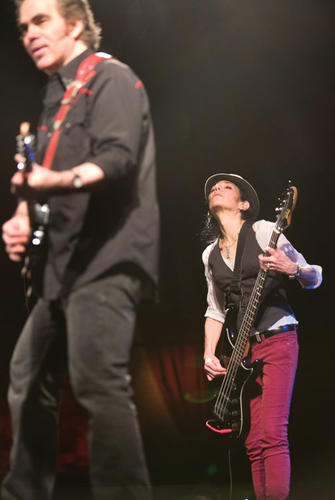

After graduating with a degree in art history and French literature, Madden was the original “gallery girl,” buying art for a private Manhattan gallery while pursuing a Ph.D. in art restoration. When she was 30, she received a bass guitar as a gift, and she was hooked. Last June, Madden was inducted into the New York Blues Hall of Fame, and in August, she released Discarded Angels, her first CD. Single mom to a college-age son, the self-deprecating Madden laughs about leaving the “Madison Avenue-ness” of gallery life for perpetual poverty as an indie musician.

“I had played guitar growing up, but I didn’t even know how to hold a bass. And I played this one little thing and said, ‘I love this! Let me do it again. I can’t put this down.’ It was this little Mustang bass, a short bass. I put on Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Fire’ — a kid standing there with headphones on — and I learned how to play it. My first audition for a band, the guy says to me, ‘You got the gig because you’re a girl.’

“I showed up at these jams, totally self-taught and not very good. The Limelight [nightclub in New York City] had a series called Legends of Rock and Roll, and for some reason, they called me to back up John Lee Hooker. That was life-changing. I walk in and John says, ‘That’s the bass player? Ech.’ And he goes to me, ‘I don’t ever do no 12-bar blues. I’ll just change when I change.’ I was terrified. This guy with him told me to just play quarter notes, but after a minute, I went back to playing what felt natural. That just changed my bass playing. I thought blues was boring before then — ‘Oh, it’s just three chords.’ But it’s about really listening and playing what’s appropriate for the moment. You’re always in the moment.

“I write all the time — it’s my outlet — and I guess I’ve got sort of a reputation, because this horror-film director came to me and said, ‘I need the darkest music in the world, and I heard you write the darkest.’ I had to write a song called ‘The Color of Blood,’ and when we recorded in the studio, it was just me playing my guitar. The director said, ‘I want deadpan. You can’t sing any vibrato, no emotion, it has to be totally live with mistakes and vulnerability.’ The movie never came out, the director ended up in jail for something, and I got an album out of it.

“Bass is a very blue-collar kind of thing for me. My style is about the intersection of great emotion and economy of musical language. It’s not the notes but where you put them, so they don’t mess up the music. Because it both is and is not simple to communicate a feeling — and that’s what decent music does.”

Deborah Hurwitz ’89

Hurwitz’s career has been a concoction of composing (including for CNN and Guiding Light), music directing (Cirque du Soleil’s IRIS), conducting and performing (Broadway’s Jersey Boys), and producing/songwriting (two CDs under the signature of alter ego Deborah Marlowe). Now established enough that her mortgage need not dictate her gigs, she says it’s time to do what she loves. But she has no regrets about her more commercial triumphs.

“I have to say, being vocal director on ‘Elmopalooza’ [1998] was a career highlight. The legends who do the voices — you know, Big Bird, Elmo, Kermit — they needed someone who could get the most musical performances out of them, and someone who could conduct. So I was up on this 30-foot ladder, lit from above as the Muppets and muppeteers were staged on various levels below. It was moving — not only because I got to be inside something very magical to me as a child, but there I was, helping to create it now.

“Then there was the naked opera I conducted at the Burning Man Festival. When I jumped in, in 2000, I jumped in at the deep end. The ‘Burning Man Opera’ was this enormous project — a choir of 40, a band of 20, 600 dancers, and two 30-foot-tall sculptures that were burned in effigy at the end. Yes, I was wearing just full body paint. So were hundreds of other people. I, however, was the only one in feathers and sparkly red high heels!

“There are lots of times, when gigs came up, that I went not in the direction of passion and fulfillment, but in the direction of, ‘OK, what adds up to the mortgage?’ Now, ‘Jersey Boys’ and Cirque du Soleil were dream gigs. But Cirque was the most crazed I ever was, so even the great gigs can take a high personal price. I did an indie feature this summer that paid me, like, $3, and now I’m starting on a live stage show this fall with [‘Seinfeld’ actor] Jason Alexander, so I get to laugh for the next couple of months and be writing and music-directing.

“What makes me happy with music is to use my whole brain and not dumb anything down or apologize to anyone, and yet call upon those universal themes of appeal and access. And make things that draw people in, move them, and make them happy. I want to bring those worlds together — the deep and the commercial.”

Rob Curto ’91

Curto is a politics major who followed his heart — and his Sicilian grandmother’s misplaced dreams — into a music career as accordionist, composer, arranger, and honorary Brazilian. This summer his band, Matuto, will travel to West Africa with the State Department’s American Music Abroad program.

“My grandmother wanted my father to play the accordion in the ’40s. But he was an Italian-American kid in New York. He wanted to fit in, so he played saxophone. Somehow, not consciously, it eventually came to me. I was living in Manhattan, working as a keyboard player, and I happened to walk by the Museum of Natural History and saw Buckwheat Zydeco playing the accordion. You know when a light goes on in your head? I was like, ‘This is something I want to do.’ I bought an instrument.

“There’s a style of music in the Northeast of Brazil called forró, a dance music analogous to what Cajun and zydeco music is to Louisiana or merengue is to the Dominican Republic. The accordion is the central driving instrument. These musicians I met asked me to play a small gig at a Brazilian sports-bar club in Queens. I started turning down better gigs to go play there. It was partially the dancing — the energy you get back from the crowd, from making people move. But I was also just totally connecting with that roots music.

“I ended up subletting my place and going down to Brasilia, staying there for six months and practicing for hours, playing at night, learning a lot about not only music but culture, people, language. I think it’s really important, in terms of learning how to play a style of music, getting that stuff in your eyes and ears.

“The first accordions came around in the 1830s and 1840s in Austria. It’s basically a harmonica. The first one just had buttons. A piano keyboard wasn’t attached till the 1920s. It went to different places through the European immigrants — they took it to the Caribbean, South America, Mexico, Texas, all over. And it changed wherever it went. The instrument went through the whole Lawrence Welk period, where people saw it badly played and badly presented. But that changed when people like Paul Simon started to use the accordion, and it has a presence now in pop music.

“I knew I was accepted as almost a Brazilian native when we played at a festival in Recife last summer. I was there, singing in Portuguese an older, traditional song — me, an Italian-American from New York! — and the Brazilian people in the front row were singing right along with me. That was an amazing feeling.”

Sandra Sobieraj Westfall ’89 is the Washington bureau chief for People magazine.

3 Responses

Steve Schaeffer ’73

10 Years AgoMusic at Princeton

Your Jan. 16 music issue stirred many memories of concerts attended in the early ’70s, but it was your profile of Stanley Jordan ’81 (“Profiles in music”) that reminded me of the time that, as the administrator working with the Madison Society, which served meals in Chancellor Green in the late ’70s and early ’80s, I was looking for musicians to play at Friday dinners.

I was given the name of a senior who was purportedly a talented guitarist — Stanley Jordan. So I called him up in his room and asked if he’d be willing to play for the students during dinner. He agreed, and I asked how much he would charge. As I recall, his answer was basically: “Whatever.” Mindful of our limited budget, I offered an amount I hoped would be acceptable: $40. Without hesitation, he again agreed, and we were treated to a wonderful performance in his signature two-handed guitar-neck style.

About 20 years later, as a renowned jazz guitarist, he was a featured performer at McCarter Theatre. I smile when I think about the cost of my single ticket that night: $40.

[node:field-image-collection:0:render]Wilhelmus B. Bryan III ’47

10 Years AgoMusic at Princeton

Congratulations on your “celebration of music” issue! What you omitted is recognition of the great leaders who built the music department into one of the strongest departments of the University, e.g., Roy Welch, Roger Sessions, and Merrill Knapp.

John C. Stone II ’53

10 Years AgoMusic at Princeton

I was sorry not to see included Ed Polcer ’58, who has played for U.S. presidents, at Grace Kelly’s wedding, and at virtually all Princeton reunions since he graduated. He is arguably the finest traditional or Dixieland jazz cornetist and band leader in the country.